Jorella Andrews is Professor of Visual Cultures, Goldsmiths, University of London and is an Associate Fellow of the KLC.

“Then I looked up and saw four horns. So I asked the angel who was speaking with me, ‘What are these?’ And he said to me, ‘These are the horns that scattered Judah, Israel, and Jerusalem.’ Then the LORD showed me four craftsmen. I asked, ‘What are they coming to do?’ He replied, ‘These are the horns that scattered Judah so no one could raise his head. These craftsmen have come to terrify them, to cut off the horns of the nations that raised their horns against the land of Judah to scatter it’.”

(Zech 1: 18–21 HCSB)

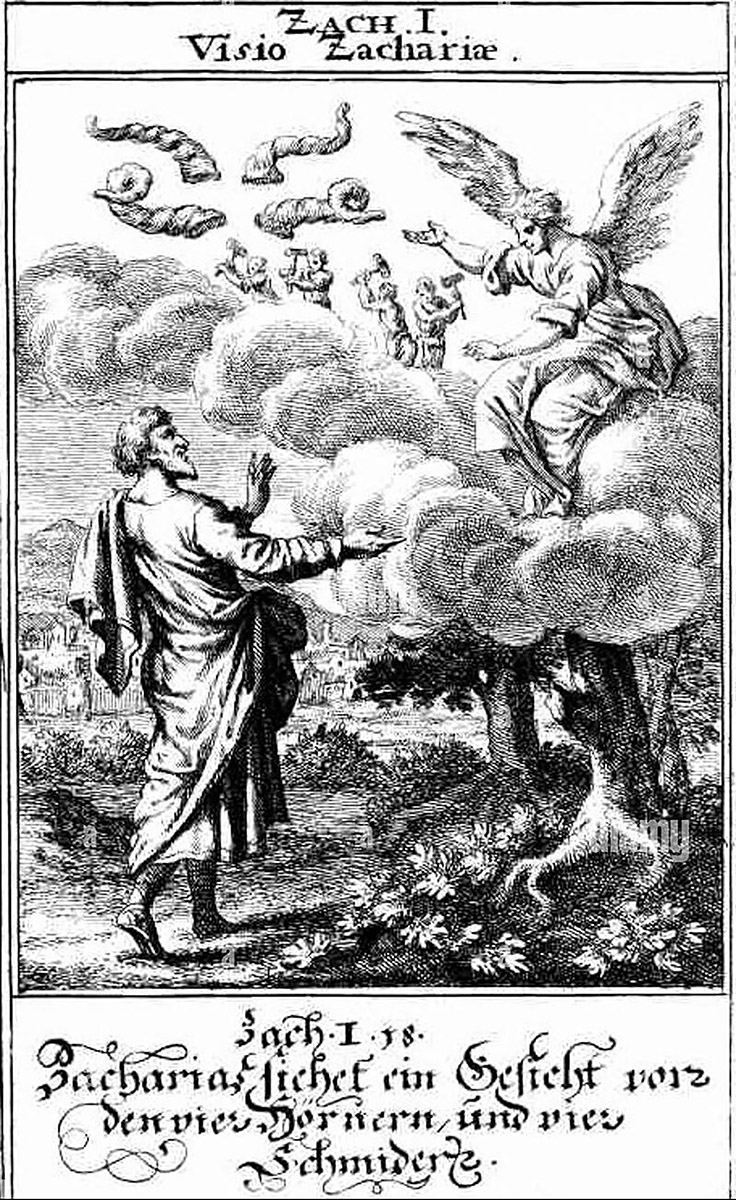

The German engraver, art dealer and publisher Christoph Weigel the Elder’s copperplate engraving, Zechariah’s vision of the four horns and four craftsmen, is an early modern attempt at picturing Zechariah’s singular vision. In Weigel’s rendering – one of 830 images contained in his remarkable pictorial Biblia Ectypa (Augsburg, 1695) – the prophet’s everyday reality, a tranquil rural setting with distant city, is being rolled away. Mediated by an imposing angel, a schematic alternative realm of crisp symbols against a white background comes into view in which four immense, twisting animal horns are being pursued by the craftsmen who are wielding the tools of their trade like weapons.

Over the millennia, art making and craftsmanship have often been associated with warfare, literally and figuratively.[1] Think of the many works designed to uphold violent or deceptive ideologies as well as those created to oppose, expose or undermine social, political, cultural or economic factors regarded as malevolent – as in modern and contemporary protest art. In each case, albeit for opposing reasons, intentions and actions are in play that are marked by degrees of aggression.

At first sight, Zechariah’s apocryphal account of craftsmanship and Weigel’s rendering of it appear to fall into the category of oppositional art making. As such, it appears at odds with the dominant ways in which godly craftsmanship is described elsewhere in the Bible, notably with respect to the construction – to God’s specifications, and yet with immense technical and spiritual imagination – of physical places of worship in which God would manifest his glory on earth (Ex 31, 36; 1 Kings 5; 2 Chr 2). The first such place, created during the Israelites’ post-Egyptian years of desert wandering under the leadership of Moses, was a mobile structure, the tabernacle; the second, built 500 years later, during the reign of King Solomon, was intended to be a permanent structure, a temple in Jerusalem. In each case, the overt focus was on collaborative divine/human making, not breaking. God’s instructions indicated environments of precisely measured and yet exceptional, even extravagant, material beauty and symbolic[2] resonance. And the craftsmen, skilled at working with wood, metal, stone, dyes, yarns, fine linens and precious stones, were also described as full of the Holy Spirit and of wisdom. In Proverbs 8, significantly, wisdom itself is defined as “a skilled craftsman,” “brought forth by God as the first of his works” and positioned alongside God before the creation of the world.

In Zechariah’s vision of the horns and the craftsmen, by contrast, an art of war and, conversely, a war of art, take centre stage. But when this passage is considered with reference to the book of Zechariah as a whole, we see, in fact, that exceptional, unforeseen forms of creativity are again at issue and warfare of an entirely other, unworldly, and counter-cultural nature. As such, this account of craftsmanship – not, as far as I am aware, commonly discussed in Christian apologetics for the urgency and worth of Christian art making – offers exceptional insight, especially, as I will show, for artists who want to see their work play a collaborative role in refashioning the sites of human brokenness that surround us. “Your kingdom come, your will be done, on earth as it is in heaven” (Matt 6:10).

***

The historical context of the book of Zechariah is crucial here. It references the post-exilic period when God’s people had been released back to their own land after seventy years of bondage in Babylon. Specifically, it is a powerful, prophetic call to resume the building project begun some twenty years earlier as authorised by a remarkable edict published in 539 BCE by the Persian king, Cyrus the Great, whose forces had destroyed Babylonian supremacy: the core task of reconstructing Jerusalem’s long-ruined temple and public spaces. As indicated in Haggai 1, most people had become more focused on building homes for themselves. Crucially, the rebuilding of the temple and the city was to be neither retrograde nor defensive. It was meant to convey an enlarged post-exilic vision that God had already begun to communicate to, and through, the pre-exilic prophet Isaiah: “From now on” (Isa 48: 6b–7), “I will tell you of new things, of hidden things unknown to you. They are created now, and not long ago; you have not heard of them before today. So, you cannot say, ‘Yes, I knew of them’.” And indeed, in Zechariah (2:4–5; 10–13) we read that Jerusalem was to be “inhabited without walls because of the number of people and livestock in it.” Why? Because God himself would be “a wall of fire around it” and “the glory within it.” Witnessing this, “many nations” – namely, Gentiles, including former enemies – would “join themselves to the Lord.” God’s desire was for a profoundly non-self-protective approach to re-establishing Jerusalem, with the intention of welcoming as many as wished to come.

God’s expansive, hospitable vision for Jerusalem is reflected in and underlined by the name by which he persistently announces himself in Zechariah: namely, as Yahweh Sabaoth, or Lord of Hosts. This has two inflections. In Hebrew, hosts may refer literally or figuratively to a mass of people assembled for war. Thus, Yahweh Sabaoth speaks of an almighty and victorious Warrior King (Lord our Warrior) who wins our battles. But Lord of Hosts also refers to the lordship of God over all the multitudes of earth as well as heaven. Where scriptural logic is concerned, these aspects of God’s name are deeply aligned rather than contradictory. The doubled character of God’s name also relates to the image of the coming Messiah prophesied in the final chapters of Zechariah. For here, as also already in Isaiah 53 – I am citing teaching by theologian Roger Forster – the promised Lord our Warrior is shockingly portrayed through “four beautiful ‘Suffering Shepherd King’ songs that point to the death and resurrection of Jesus.”[3] Here, saving peace for all nations is proclaimed (Zech 9:10b) and, again, warfare of a very particular and paradoxical nature. Centuries later, in Jesus’ own self-presentations and self-explanations, these were the portions of Scripture he would most consistently cite. For Jesus as Lord our Warrior was a saviour not solely of the Jews but of the whole world (John 1:29), and not of a military kind, as the Jews expected, but humble and sacrificial while nonetheless established in authority over all that exists. In him, King, Priest and Peace Offering are intertwined.

***

What, then, of this paradoxical Christ-like warfare to which, in Zechariah, godly artistry is called? This “terrifying” and “cutting down”? Here, Forster is again insightful. He says that Zechariah’s second vision is fundamentally about “breaking the horns (the power) of disunity by forging unity among God’s people” – understood not in racialised terms but indicating those of every nation who are turned towards him.[4] For what terrifies the powers (literally diabolic[5]) that seek to scatter, un-home and devastate? Not the varied responses of counter-violence that are so easily deployed including, as noted, by oppositional forms of art-and-craft activism. For violence loves violence, feeds off it, and multiplies it like a virus. Required instead, is a radical movement informed by an entirely alternative spirit, proceeding from a platform of peace, by which attention, matter, hard truths, beauty and symbol can intersect to serve the human/divine, human/human, and human/world realignments we need today. But working in this way persistently and well needs divine empowerment. Zechariah 4:6 is instructive. “Not by strength or by might, but by My Spirit,” says the Lord of Hosts to Zerubbabel, the Prince of Judah who was responsible for the rebuilding work in ruined Jerusalem, that seemingly impossible task. “What are you, great mountain? Before Zerubbabel you will become a plain. And he will bring out the capstone [a term drawn from the building trade] accompanied by shouts of: Grace, grace to it.”

In times of pressure, a commitment to craftsmanship, within devastation, for the sake of unity – which horns am I called to terrify? – requires unflinching focus on Yahweh Sabaoth who throughout Scripture, from the creation accounts in Genesis to the re-creation accounts in Revelation of a new heaven, new earth, and new Jerusalem, also reveals himself as Master Craftsman. We must remember that in Zechariah a devastating effect of “the horns that scattered Judah” was that “no one could raise his head.” That is, physical and, above all, spiritual vision were diminished. No wonder then that before that call to rebuild, the book of Zechariah opens with God’s insistence that the geographically returned people of God also return to him (Zech 1:1–6). Here, again, the promised Messiah, Jesus, – who for most of his life on earth worked with his human father as a craftsman (Mark 6:3) – is our paradigm as we witness him, in Scripture, continually configuring and reconfiguring his constant orientation of turned-ness towards God. Recently, the psychologists Joshua J. Knabb and Kevin P. Newgren attempted to account for “the firm sense of self” displayed by the scriptural Jesus throughout his lifetime. They described him as “ripe with temporal continuity, self-esteem, ambition, values, ideals, and a sense of belonging, purpose, and power.” How and why? Because he was rooted in an ever-deepening relationship of apprenticeship to God the Father as his Master Craftsman.[6] This “firm sense of self” was vital since, as indicated, his saving work would so definitively counter long-held Jewish expectations. To repeat, it would be sacrificial, not militaristic.

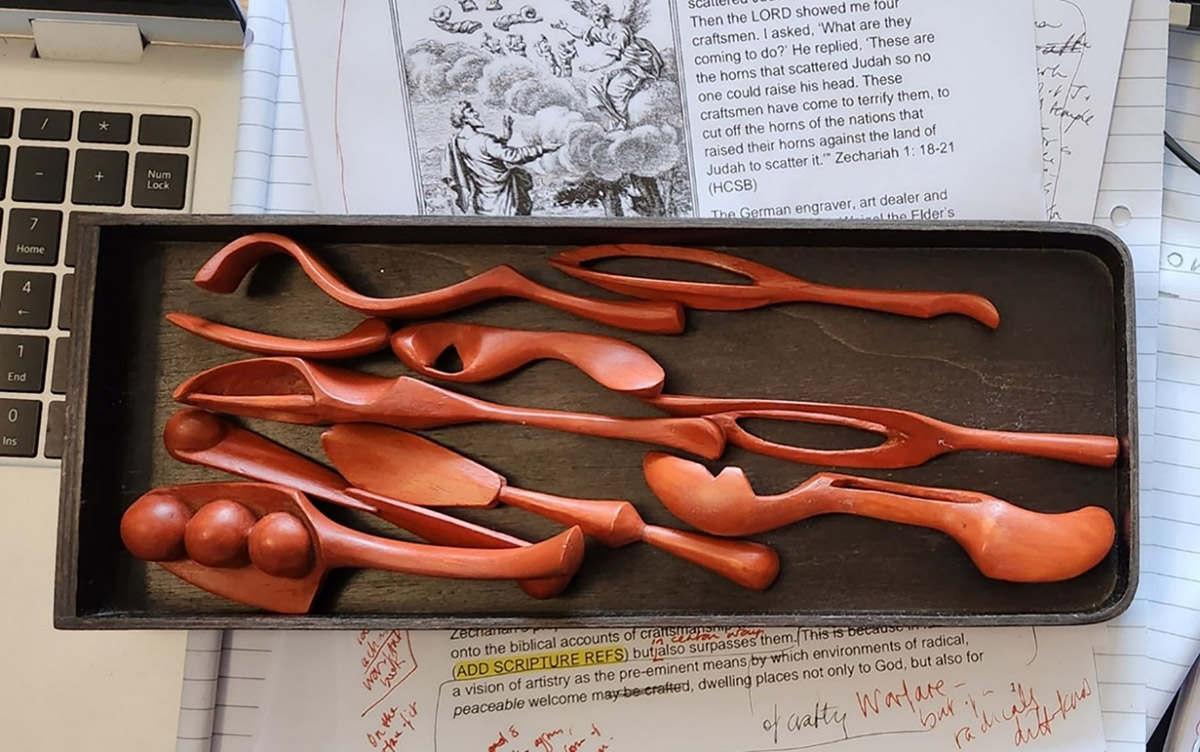

On my desk is a wooden tray. It holds a series of small works of art, a set of strange “tools” – or peaceable weapons? – crafted by the South African artist Gert Swart. He calls these objects “Findings,” a term that refers to the clasps, links and rings that hold pieces of jewellery together and make them wearable. Swart’s Findings were made to be handled and accompany me as I work. I see them as God-inspired, urging me to keep reaching into as-yet unknown terrain, glimpse something of God’s ways and thoughts, so much higher than our own (Isa 55:8–9), and participate as skilfully as I can in forging the new, diverse, sacrificially-generated unities that are certainly in God’s sightlines.

[1]. In the ancient world, the potency of craftsmen was widely acknowledged. Thus, when the tragedy of Jewish exile into Babylon occurred “all the men of might, even seven thousand, and craftsmen and smiths a thousand, all that were strong and apt for war, even them the king of Babylon brought captive to Babylon.” (2 Kings 24:16 KJV, emphasis mine).

[2]. From the Greek symbolon, meaning to throw or cast together, that is, unify.

[3]. Roger Forster, “Zechariah,” in Right Through the Bible: Old Testament, audio recording, Ichthus Christian Fellowship, August 2017.

[4]. In Jewish tradition, Zechariah’s craftsmen have been variously interpreted. Some interpreters understood them as symbolic representations of Gentile kingdoms who exerted a kind of redemptive power by overthrowing nations that had themselves overthrown God’s people (such as Persia, whose victory over Babylon meant that it was possible for the long-captive Jews to return home). In the Talmud there is a tradition of identifying the four craftsmen with four figures of redemption “The Messiah the son of David, the Messiah the son of Joseph, Elijah, and the Righteous Priest.” (See: Sukkah 52b, Dr Joshua Kulp, The William Davidson Talmud, accessible via https://www.sefaria.org.)

[5]. From the Greek diaballein: to throw apart, separate, compartmentalise.

[6]. See Joshua J. Knabb and Kevin P. Newgren, “The Craftsman and His Apprentice: A Kohutian Interpretation of the Gospel Narratives of Jesus Christ,” Pastoral Psychology 60/2 (2011): 245–262, 24. Accessed 26 November 2023, doi: 10.1007/s11089-010-0311-x.

The Kirby Laing Centre for Public Theology in Cambridge. Charity registered in England and Wales. Charity Number: 1191741

Kirby Laing Centre, The New Mill House, Unit 1, Chesterton Mill, French’s Road, Cambridge, CB4 3NP

© 2022 The Kirby Laing Centre for Public Theology in Cambridge