Estelle is a retired art historian and paper conservator. She undertakes conservation work from home and makes artists’ books, often with a Christian theme.

Extensive research is available on the origins, content and language of early Christian manuscripts. However, not much information is readily available on how these manuscripts were assembled and bound into what eventually became the “books” of the New Testament. A number of book historians agree that very little is known about bookbinding structures used until the early Middle Ages. This is because the original bindings were often dismantled and discarded by researchers and historians so the text could be photographed, documented and studied; sometimes the loose pages were even sold at various markets. While Christian texts clearly survived, the actual bindings dating to the first two centuries AD do not seem to exist. As a Christian who makes artists’ books, I kept asking: what did the earliest Christian books look like?

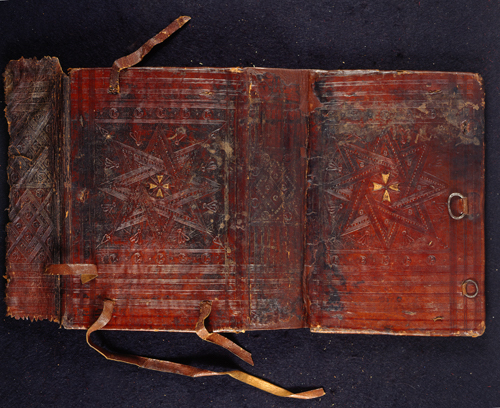

However, this article is not about the history of bookbinding; neither will it delve into any theological issues, but it focuses on my question. The Coptic Christians bound their texts from ca. AD 400 using a decorative chain stitch to link one quire to another. Wooden boards were then added as covers and the whole covered with leather. The front cover was decorated with leather tooling and often gemstones and precious metals were added.

Is it possible that the format chosen by the early Christians, namely the caudex or codex (or book) format, derived from the antique Roman wooden wax tablets? These tablets consisted of a set of small wooden boards covered with wax. Notes such as personal notes, accounts, receipts and even legal information were written into its surface using a stylus. Once the information was redundant, the surface could be smoothed over and re-used. A number of these waxed, wooden sheets were bound to form a caudex or codex either by lacing leather thongs through holes along the one edge or inserting metal rings, resulting in a book-like structure. The Romans also used pugillares membranei or parchment notebooks. These were small and used for personal notes. Our current-day books derive from the codex form.

Whether the early Christian codex derived from the wooden waxed tablets or the smaller pugillares is not clear. What did become clear was that the early Christians chose the codex format not only to distinguish between their sacred texts and those of the Jews, but also from other secular texts, which were, like Jewish texts, also written on scrolls. Jewish sacred texts, along with secular and literary texts of the antique period, were written on papyrus or parchment sheets which had been pasted together into long strips and rolled up into scrolls. While scrolls were often wound around a central cylindrical core, to be read either by winding it horizontally or vertically, the Jewish Torah used two cylinders to access the text from the beginning or the end: one cylinder is rolled to release the text to be read while the other winds up the text already read.

According to Larry Hurtado and Chris Keith in “Writing and Book Production in the Hellenistic and Roman Periods,”(1) the codex format was also not widely used for literary texts until the fourth century AD. The standard form for books was scrolls which could easily be made, while making a codex required a specific skill, knowledge, and preparation and planning of the pages. For the early Christians to choose this format was therefore significant. Hurtado and Keith note that some of the earliest fragments of Christian codices date to the mid-second century AD, and that these scriptural texts in codex format therefore differed radically from all other liturgical texts which were written in scroll form. Many of the earliest Christian texts on papyrus contain a vertical row of punctures down a central fold, indicating where the original binding was done, and that these texts were not written in scroll form. This clearly indicates that for the early Christians, the choice of the codex for the Bible indicated its holy and sacred identity.

Hurtado and Keith conclude that the preference for the codex format was not based on the practical advantage of a small, compact item which could easily be transported. Some biblical codices were quite large, making them cumbersome to use while travelling. This choice had centred on a specific, Christian identity, a conclusion supported by another important point which Hurtado and Keith raise, namely that unlike non-biblical codices, the biblical codex had wide margins and fewer lines with “generously sized” writing. The text appeared to be written with “little concern to make the maximum use of the writing space.” No skimping was suitable for a holy text! Also, Hurtado and Keith note that these earliest Christian codices were written in a “legible and practised hand,” unlike the “elegant pagan literary rolls of the time, and also in some early Jewish copies of biblical texts.” Hurtado and Keith conclude from this that, although the early Christians did not have professional calligraphers among them, they did not want non-Christians to write up or copy their sacred texts. The scroll and the codex, therefore, co-existed for at least the first four centuries AD but the codex gradually became the dominant form of binding books. Eventually, Judaism accepted the codex structure for its religious texts.

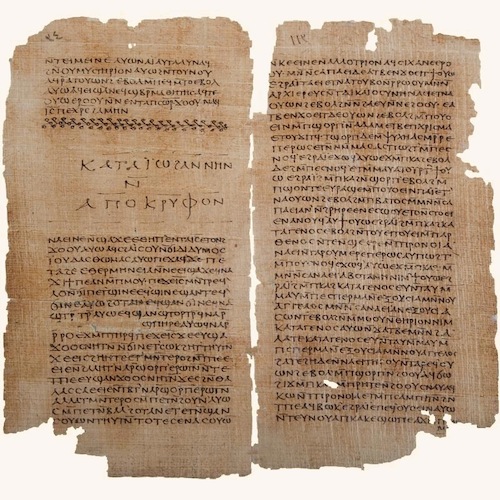

Regardless of how interesting and significant this information is, for me the central question remains. Looking at the bindings of the Gnostic texts found in 1945 at Nag Hammadi, some indication was given: these early codices were written on papyrus and bound as single or double quires into papyrus or leather covers with flaps and thongs at the top, bottom and front to tie it all up. But the Nag Hammadi codices are dated to the third and fourth centuries AD, leaving the question of the earliest Christians bound texts unanswered.

The leather thongs on three sides of the Nag Hammadi codices offered a possible answer, allowing my imagination to conjure up some basic binding possibilities: single sheets were compiled, wrapped and tied up in a parchment or papyrus cover. Thongs along the open ends: top, bottom, and fore-edge, were tied to secure the contents of this “folder,” Alternatively, single sheets were compiled and probably loosely tied along the left edge, so that they could function like the pages of a book, following the example of Roman wax tablets. Loose sheets could also be folded, trimmed and bound along the centre. Following the Nag Hammadi codices, quires might have been sewn into leather covers, retaining the practice of tying everything together along the open ends to prevent losses. However, for me, this mystery continues, but the fact that the early Christians wanted to distinguish their Bibles from texts generated by a secular world, eventually resulted in the wonderful world of printing, binding and reading books. That makes each book a potentially sacred site.

The Kirby Laing Centre for Public Theology in Cambridge. Charity registered in England and Wales. Charity Number: 1191741

Kirby Laing Centre, The New Mill House, Unit 1, Chesterton Mill, French’s Road, Cambridge, CB4 3NP

© 2022 The Kirby Laing Centre for Public Theology in Cambridge