Dr Philip J. Sampson, is a Fellow at The Oxford Centre for Animal Ethics and Consultant Editor for the Journal of Animal Ethics.

“There is,” says the proverb, “a place for everything and everything in its place.” In 1675, John Hacket, Bishop of Lichfield, elaborated: “The Lord hath set everything in its place and order.” So, what place did God give food?

It depends upon the food. The culinary place for every seed-bearing plant and every fruit-bearing tree starts in Eden (Gen 1:29–30). For John Calvin, the vegan diet of Eden was “abundantly sufficient for the highest gratification,” “a liberal abundance which should leave nothing wanting to a sweet and pleasant life.” The promised land is the vegetarian place of abundance: grapes, pomegranates and figs (Num 13:23); the kingdom of God is the place for a bloodless feast – after all, the lamb is to lie down with the wolf, not within the wolf (Isa 11:6–9; 65:25).

The place of animals is not on a plate, but to praise and disclose their great creator, to sing out in praise and joy. (1) The church has sung out these truths most weeks for many centuries. From Thomas Ken’s (1674) “Doxology” (“Praise God from whom all blessings flow; praise Him, all creatures here below”), to Kari Jobe’s “Revelation Song” in which we join all creation in singing praise to the King of kings.

Our family had little of this in mind when we first began to move to a plant-based diet some fifty years ago. It was not because we were especially aware that the purpose of creation is to praise and declare God; (2) nor for epicurean reasons of “the highest gratification,” as Calvin put it. Discovering the pleasures of a plant-based diet, and insight into the biblical meaning of creation came later. Rather, it was because we had learned that our dietary choices were directly contributing to the malnutrition suffered by many in the developing world. For us, it made no sense to campaign for social justice while undermining our message with our actions. Moreover, to us, a change of diet seemed a small effort for the improved nutrition of malnourished children. Only later did we find it hard to sing with integrity one of the many songs based on Psalm 148, from Thomas Ken to Kari Jobe, while knowing we would go home and eat the choir.

But look around you. The world is no longer an Eden, or even a promised land; and God gave animals to Noah to eat.

Our fallen world is without doubt a place of dietary scarcity, suffering and death. Since the flood, fleshpots have sometimes been necessary for survival in this sinful world. It was, observed the Calvinist, Thomas Adams in 1629, “sin that made us butchers, and taught the master to eat the servant.” Yet, God is merciful to his animals, and constrains our cruelty. Noah was commanded to ensure the animal was dead before butchery began (Gen 9:4), outlawing the practice of cooking an animal while yet alive. The Mosaic covenant declared “unclean” (inedible) those animals whose slaughter entails intense agonies: swine, crustaceans, cetaceans, cephalopods … Even “clean” (edible) animals may not be slaughtered or eaten if they bear the scars of abuse or mutilation (Lev 11; etc.). By contrast, modern factory farming relies on mutilation and abounds in abuse. Solomon in all his wisdom, warned that animal cruelty is wickedness, incompatible with a righteous life (Prov 12:10). We also have New Testament witness. Jesus relies upon his heavenly Father’s known care for sparrows to demonstrate his care for us (Matt 10:29). His reputation for making “easy” yokes that do not chafe and cause pain, reassures us that discipleship is a place of care (Matt 11:28–30). Gentleness is a fruit of the Spirit (Gal 5:22). In view of this, it is unsurprising that many of our evangelical forebears took a dim view of cruelty. Westminster divine, George Walker (1641), calls it “a kind of scorn and contempt of the workmanship of God our creator.”

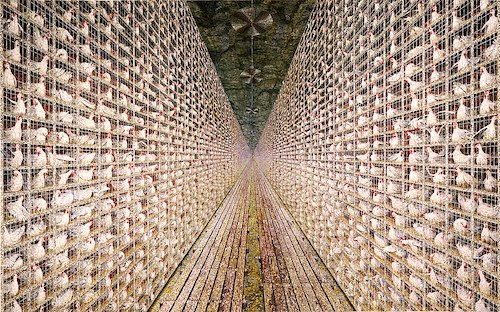

In today’s world, we don’t just eat the choir, we first hand over God’s creatures to an industry known for its cruelty. Calvin asked why God bothers to care about birds (Deut 22:6–7; Matt 10:29). He answers that he “meant to express the better, how greatly He abhors all cruelty.… Birds may seem of no value to us, but God will tolerate no cruelty to them.” Yet we tolerate it; indeed, we pay for it. In the modern meat industry, chickens are routinely scalded to death, cattle are skinned and dismembered alive. (3)

How the demons must rejoice at the sights of such butchery; how they must enjoy the cries of pain. An animal created to praise God has been reduced to screaming, quivering flesh; its agonies disclose nothing of the God of love; much about ourselves. From its violent, sinful origin (Gen 6:11–13; 9:3–4), to the cruel wickedness of industrial farms, the place of meat has always been bloody.

We live in a place where it is entirely possible to live healthily without supplementing our diet with flesh; indeed, research indicates that the low-cruelty diet of Eden is actually healthier – as one might expect of God’s plan for us.

In the wilderness places we reject God, and lust after fleshpots. God provides until we are gorged, until it comes out of our nostrils; and we bury those who lusted in their graves of desire. (4) Carnist lust kills.

The British may be an island nation, but we are no island, entire of ourselves. The place we give meat has an unsustainable global impact. It industrialises hideous cruelties, is a major source of greenhouse gases, pollutes land and sea, contributes to malnutrition in developing countries, causes ill health, is associated with antibiotic-resistant bacteria, and generates new zoonotic diseases. Does God have a place for such ruinous food in Britain today?

Recent publications by Philip Sampson:

Animal Ethics and the Nonconformist Conscience (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018).

“The Ethics of Eating in ‘Evangelical’ Discourse: 1600–1876,” in Ethical Vegetarianism and Veganism, ed. Andrew Linzey and Clair Linzey (Abingdon, Oxfordshire: Routledge, 2018).

“Evangelical Christianity: Lord of Creation or Animal among Animals? Dominion, Darwin, and Duty,” in The Routledge Handbook of Religion and Animal Ethics, ed. Andrew Linzey and Clair Linzey (Abingdon, Oxfordshire: Routledge, 2018).

“Noah, Jesus and Ecology – Sustaining and Restoring the Environment,” in Climate Crisis and Sustainable Creaturely Care, ed. Christina Nellist (Cambridge, UK: CSP, 2021), 137–151.

Further Reading:

Andrew Linzey, Animal Theology (London: SCM, 1996).

Philip Lymbery, Farmageddon (New York, NY: Bloomsbury, 2014).

See also: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0WW56dKrqeQ (Warning: explicit content).

The Kirby Laing Centre for Public Theology in Cambridge. Charity registered in England and Wales. Charity Number: 1191741

Kirby Laing Centre, The New Mill House, Unit 1, Chesterton Mill, French’s Road, Cambridge, CB4 3NP

© 2022 The Kirby Laing Centre for Public Theology in Cambridge