Jeanne (Ioanna) Knights is a theologian with an interest in the primacy of living holiness as a theological source. She studied theology at Lancaster and Cambridge and has worked significantly in the Orthodox tradition. She is the Director of The Sacred Gardens of Patmos Project (www.charis-patmos.org). Charis would welcome your support in realising its vision. Charis is able to offer “Discovering Patmos” pilgrimages: should your church group be interested in making such a pilgrimage, please email ioanna@charis-patmos.org.

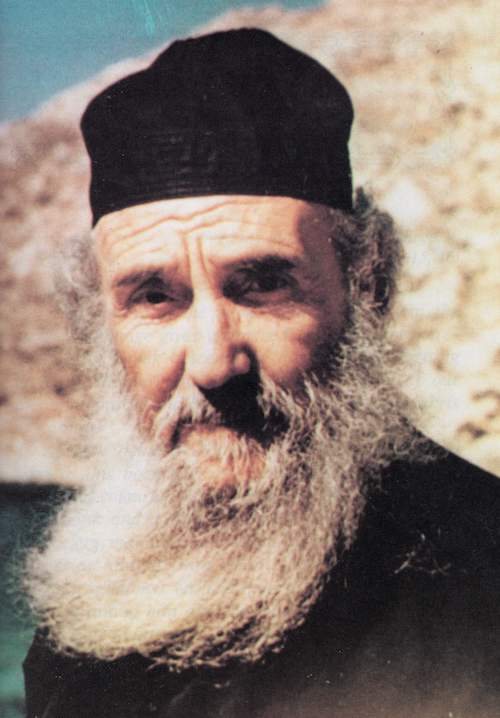

Photographs of St Amphilochios by kind permission of Metropolitan Amphilochios (Tsoukos), the spiritual heir of St Amphilochios; photographs of Patmos by kind permission of Charis.

The recently canonised St Amphilochios Makris (1889–1970) grew up on Patmos, one of the Greek islands in the Aegean that make up the Dodecanese. The island is imbued with the spirit of St John, who, in 95 AD, was exiled here.

In the late 19th century, when St Amphilochios was born, and through to 1970, when he died, the island was fully self-sufficient in the necessities of life. Born into a family of shepherds and farmers, growing up and living in such an interconnected, interdependent, microcosm of the web of life of our planet, must itself have been a great source of learning for this young man.

In 1088, the island was gifted to St Christodoulos to establish a monastery, and, at the age of 17, Amphilochios went to live in this monastery. While receiving no advanced education, he taught himself palaeography to read the remarkable manuscripts in the monastery’s library. He loved to read the Philokalia for its theory, and the lives of the Desert Fathers for inspiration for practical Christian living.

At the age of 23, Amphilochios was sent to the neighbouring island of Kos to be ordained Deacon. Instead, he sailed to Egypt, arriving penniless, determined to visit Jerusalem with the desire to become a guardian of the Holy Sepulchre. Since he acted without the blessing of his monastery, this young rebel was sent back, and given two years’ penance – to live in a remote hermitage with a monk who maintained the strict hesychastic practice of the Jesus Prayer. He was later to say of this time: “What was inflicted on me as punishment, turned out to be the greatest blessing of my life – it deepened my love of stillness.”

Amphilochios grew to become a man of both courage and sensitivity.

In 1935, at the age of 46, he was elected Abbot, at a time when the island and the entire Dodecanese were under Italian occupation. He fiercely resisted both the rule of the occupiers and their attempts to obliterate the traditions of the islands, setting up secret schools to ensure that the Greek language and Orthodox faith continued to be taught to the children, and professing monks without the approval of the Italian authorities. He showed formidable determination and was labelled “a dangerous rebel”; no longer a rebel according to his own wishes, now a rebel in the service of the island, its people and the occupied Dodecanese. Soldiers finally entered the monastery, armed with bayonets, and took Fr Amphilochios away into exile, where he continued his missionary work.

Coupled with this courage, Fr Amphilochios was a most sensitive person, sensitive to the human heart. The saint’s spiritual heir, Metropolitan Amphilochios (Tsoukos), said of him:

“Besides people he had great love for all the other creatures of God. He especially had great love for trees and flowers and was the first to bring the big pine trees to the island of Patmos. Patmos had no trees before the Elder. And he had this wisdom, when a person would come and confess to the Elder with a grave sin, as a penance he would tell the person to plant a tree, and thanks to this, Patmos Island today has many trees. His example was followed by his students from the ecclesiastical school, so now we have this little woodland in this area.”

It was by this very woodland, in a cave, that St John, in earlier times, heard the word spoken by God: “And he that sat upon the throne said, ‘Behold, I make all things new’” (Rev 21:5). Few visions have had more impact on later generations than this record of God’s purpose revealed to man.

Nineteen hundred years later, by the very cave in which St John received his vision, in the woodland planted by Fr Amphilochios, Metropolitan John of Pergamon spoke the following words:

“We are used to regarding sin mainly in anthropological or social terms, but there is also sin against nature. The solution of the ecological problem is not simply a matter of management and technicalities, important as these may be. It is a matter of changing our very worldview. For it is a certain worldview that has created, and continues to sustain, the ecological crisis.”

“Sin against nature … a matter of changing our very worldview.”

And this worldview begins with how we see ourselves. To the degree to which we have severed links with our material environment, with the soil from which our bodies are made, are instructed to care for, and to which our bodies will return, we cease to express our true character. Fragmented and detached from the matter of which we speak, the temporal moment is lost, the link with the body is lost.

The sacrament of confession was a vital and central part of St Amphilochios’s life. As a confessor, he was exacting – saying that the confessor should weep and suffer more than the other. Taking a long time with each person, he wanted there to be a real opening of the heart. He aimed to give courage and hope, showing solidarity towards his spiritual children; if he imposed a penance, then he would very often also fulfil the penance himself. He cried with those who cried and rejoiced with those who rejoiced. In this way, he created a closer bond with his spiritual children. To avoid wounding the Elder’s heart, each person took care not to repeat their mistakes and stayed away from the pitfalls.

Courage, sensitivity and love are not simply human states, they are theanthropic states, embodying both divine and human states. Being incarnate, they acquire meaning, and as such, Fr Amphilochios’s life – the account of his existence and interactions with others – emanates value, from a locus unencumbered with concepts and arguments that may become confined in the intellect.

When people see such holy persons, it is more accessible and easier for them to reach Christ. And beyond seeing, also understanding, for the life force emanating value from the holy person touches real bodies, flesh and blood listeners, who may be gathered up into its narrative to extend and elaborate it with his or her own life.

I first visited Patmos in 1992. Staying at the women’s monastery founded by St Amphilochios, I heard stories of his life, stories which kept me reflecting until my next visit … and my next. And on each visit, I felt drawn to pray by his grave. In 2004, I understood: understood that I was being led to initiate a small Christian Ecological Centre … and then events unfolded rapidly. Three days later, standing on 4,500 m² of land available for purchase, amid the monasteries, and again that evening sitting by his grave, I understood how to move forward … in faith, knowing that I needed to follow.

This became our first garden – the Garden at the Holy of Holies. And then our second garden, a former farm adjacent to the Cave of the Apocalypse – St John’s Garden.

And the vision for this small Christian centre grew, a learning community in theology, life and livelihood, through a series of Sacred Gardens that bear witness to the way we relate our lives, livelihoods and relationships to the earth, … that can also have a radiating effect around the world, … just as St Amphilochios’s life continues to have.

Sacred Gardens of Patmos – a witness to the healing of our planet, each other, ourselves – leaving a legacy to inspire future generations to “live lightly on our earth.”

Our gardens are not exactly “gardens” in the botanical sense, although of course we have an eye to this, but gardens in the sense of a place where God meets man, where one can experience a dynamic connection with the earth. They are places of learning, for we ourselves need to learn, be transformed, before we can transform the world.

It would take time to tell you what we have accomplished and are doing. Perhaps you will “come and see.”

In speaking with the saint’s spiritual heir, Metropolitan Amphilochios said:

“With God’s help, and with the Elder’s blessings you will be able to complete this. The grace of our Virgin Mary first of all, of St John the Theologian, of St Christodoulos and the blessings of our Elder Amphilochios, may they always be with all of us and I hope that the dreams and plans you have, Sister Ioanna, may be blessed by these things and may they be a ray of light which will beam from the island of Patmos, from the Cave of Revelation, from the monastery of Patmos and spread up all over to enlighten and bring warmth to the hearts of people.”

St Amphilochios used to say to his many disciples:

“Do you know that God gave us one more commandment, which is not recorded in Scripture? It is the commandment “love the trees.” When you plant a tree, you plant hope, you plant peace, you plant love, and you will receive God’s blessing.”

The Kirby Laing Centre for Public Theology in Cambridge. Charity registered in England and Wales. Charity Number: 1191741

Kirby Laing Centre, The New Mill House, Unit 1, Chesterton Mill, French’s Road, Cambridge, CB4 3NP

© 2022 The Kirby Laing Centre for Public Theology in Cambridge