Aston Fearon lives in Nottingham with his wife and is part of a local church who meet there.

On the surface of it, humankind knows more now than we ever have in history. Scientific knowledge and its applications have increased exponentially in recent history and perhaps show no sign of slowing down. Yet for many of us in Britain (and probably most in modernised, industrialised, capitalist societies) we live in a peculiar position.

Humankind in this kind of society as we know it is characteristically more and more alienated from reality and the knowledge of things. For example, many of us aren’t acquainted with how the food we eat ends up on our plates. We might personally purchase groceries from the shop but we are separated from the experience of the realities of raising food – and all that involves. Perhaps we know something of the supply chain of our local supermarket – or perhaps not. But do we know what a squash plant looks like and how its flowers and fruit develop? G. K. Chesterton put it well:

“What is wrong with the man in the modern town is that he does not know the causes of things … He does not know where things come from; he is the type of the cultivated Cockney who said he liked milk out of a clean shop and not a dirty cow.” (1)

Despite the fact that eating is such a common activity, we organise our society so that most don’t actively participate in experiencing the sources of these things.

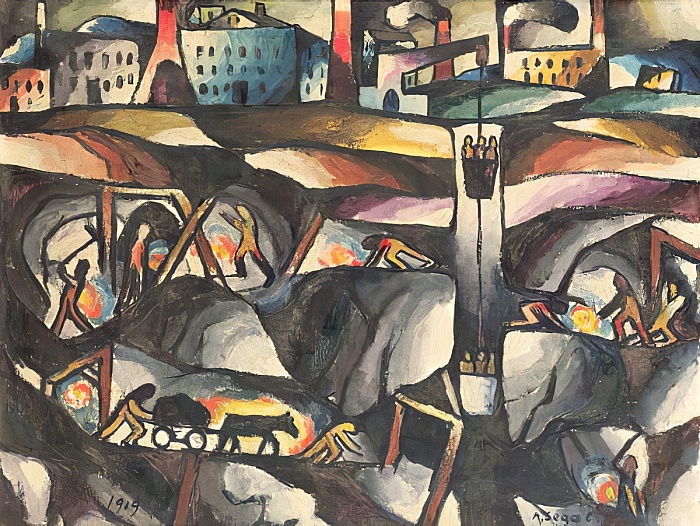

However this isn’t just what may be seen as an agricultural phenomenon. A variety of factors encourage us to focus a high proportion of time specialising for work in specific roles in paid employment in order to provide for a division of labour. Higher education and postgraduate study is prized and often a unique privilege for those who can partake in it. However in these and other environments a certain narrowing of focus can take place. This narrowing is arguably characteristic of much of society and without other valuable input, can lead a fuller experience of all of reality to atrophy. Often the realities of industry and public life can leave us so busy and focused on meeting certain targets that we are unable to be present to realities that exist even within our own field of work. Writing in the fifties in his work The Technological Society, Jacques Ellul claims:

“Man as worker has lost primary contact with the primary element of life and environment, the basic material out of which he makes what he makes. He no longer knows wood or iron or wool. He is acquainted only with the machine … Men with scientific knowledge of materials are found only in research institutes. But they never use these materials or see them and have merely an abstract knowledge of their properties. The men who actually use the materials to produce a finished product no longer know them…” (2)

Ellul’s hyperbole could grate on some but his point is illustrative. How many scholars or authors have witnessed the paper-making process? How many of us know the materials that are in our smartphones – what they are like and how they are drawn from the earth? Is it common for the marketing executive, remote-working in a cafe, to know anything of the leather sofa she sits in? Or if it’s even leather at all?

Scripture reveals Jesus to us, the image of the Father and the only way of salvation. It also reveals Christ as the agent of creation (along with the Father and the Spirit):

“He is the image of the invisible God, the firstborn of all creation. For by him all things were created, in heaven and on earth, visible and invisible, whether thrones or dominions or rulers or authorities – all things were created through him and for him. And he is before all things, and in him all things hold together.” (Colossians 1:15–17. See also John 1:1–5 and Hebrews 1:1–3.)

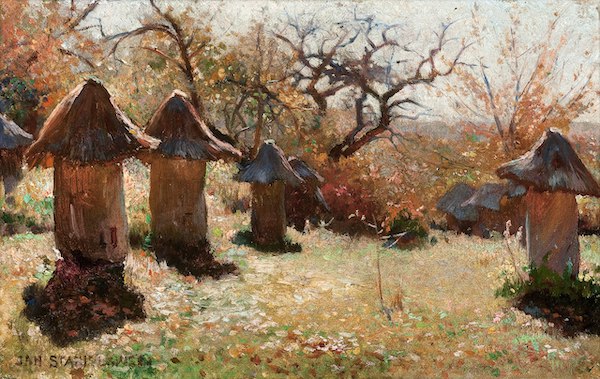

If all of reality is God’s creation sustained by Christ, surely Christians are invited to be acquainted with the reality of God’s creation and the way things are. In its proper context resistance against our alienation from creation has value. Not only can it put the reality of God’s creation in plain view in all its complexity, but it also offers a window into the variety of aspects of dominion which humanity is undertaking even amidst the curse of the fall.

Any constructive responses that we aim for should probably avoid being too narrowly prescriptive to all people – after all, creation is vast and humanity is diverse in its gifts and abilities. However we do need to translate doctrine and theory into concrete lived realities – and opportunities abound in both the commonplace and the surprising. As an example, allotments are not new yet recent years have brought a resurgence in people being more involved in raising food. Reputable courses exist to learn skills from soap making to jewellery making. We can all become more interested in the materials we are using every day whether in laptops or pushchairs.

It’s a part of God’s grace that unbelievers too can aim to appreciate God’s creation and grow in skill and knowledge in developing it – even if they don’t have a Christian faith. There are voices outside of Christianity decrying the dangers of various forms of this alienation and advocating for living, eating and working that is more in touch with reality as it actually is. Yet of all people Christians have a unique opportunity and responsibility to be in touch with a wide experience of reality – while growing closer to the one who made it all.

The Kirby Laing Centre for Public Theology in Cambridge. Charity registered in England and Wales. Charity Number: 1191741

Kirby Laing Centre, The New Mill House, Unit 1, Chesterton Mill, French’s Road, Cambridge, CB4 3NP

© 2022 The Kirby Laing Centre for Public Theology in Cambridge