Paul Glader chairs the Journalism, Culture and Society programme at The King’s College in NYC. He is also executive director of the international nonprofit organisation, The Media Project, and its award-winning, nonprofit news outlet, ReligionUnplugged.com.

NEW YORK – The news about the news industry, once again, rang grim this summer. The facts were clear and not heartening. And they pointed to a distinct set of problems.

Viewership on Cable TV channels plunged 19 percent in the first half of 2022 compared to 2021. Traffic on the top 12 most popular news apps was down 16 percent in the same time period. Engagement with news articles on social media also dropped 50 percent in the same time period according to a firm called NewsWhip.

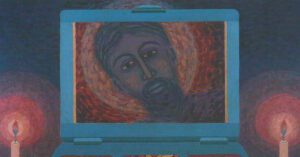

Americans are increasingly sounding like the poet in Ecclesiastes when he says in chapter 1, verse 2, “Meaningless! Meaningless! Utterly meaningless! Everything is meaningless.” It could be that the book of Ecclesiastes is one we should return to when considering our news and information quandaries.

Other studies this summer of 2022 show citizens turning more nihilistic on the news, less interested and less engaged with news media products. Blame Covid-19 fatigue! Blame the war in Ukraine! Blame the increase in tribalism in America. Blame gender ideology that increasingly alienates conservative and religious audiences. Blame social media platforms that create an amalgam of “content” that often confuses, misinforms, addicts and wearies readers who slog through the endless stream of information.

The impact of this disinterest from American consumers seems to be most pronounced and dire when it comes to local news. In late June, research showed that 360 more newspapers in America, almost all of them weeklies, closed shop since 2019. That’s on top of the 2,500 newspapers closed since 2004 in an earlier survey by Penelope Muse Abernathy at Northwestern University. Vulture-investing hedge funds are buying up the carcasses of some newspaper chains. Newsroom employment has gone from 114,000 in 2008 to 85,000 in 2020 in the United States. And nearly 1,800 communities across America have no local news outlet, leaving them veritable news deserts.

Business journalism as a refuge

Amid the carnage, it seems business journalism is a slightly safer place for reporters and publishers. The jobs tend to pay better, roughly $66,204 in median salary per year for reporters, nearly $100,000 for editors, according to the 2022 study from the Donald W. Reynolds National Center for Business Journalism, based in Phoenix. Circulation and revenue also seem more stable. Business readers often have corporate credit cards to expense subscriptions as they need accurate news and information to do their job.

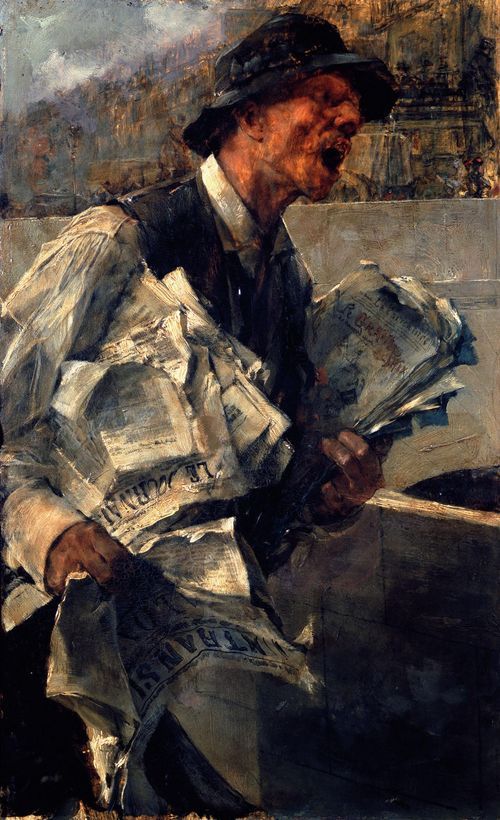

Mitchell Stephens, a journalism professor at New York University, points to business journalism as a beginning of the news business in his book, A History of News. Humanity emerged from the oral storytelling tradition of Ancient Greeks, tribal societies and European town criers in coffee shops and public houses. Commerce became an early topic for written news. In the 16th century, Venetian merchants received written reports of the spice trade from India to Portugal. They also learned of movements of the Turkish fleet, which threatened their trade business. Early banking entities from Italy such as the House of Fugger used private written reports and correspondents to provide key information in finance and business as well as movements of the Spanish armada. News sheets emerged in continental Europe (present-day Germany) with Johannes Gutenberg’s letterpress spawning printed products in religion, commerce and other topics.

Such innovation continues into the 21st century. While many local news outlets are collapsing, business journalism appears to be flourishing. Outlets such as The Wall Street Journal, The Economist, Financial Times, Bloomberg, CNBC and Forbes continue serving massive audiences in the millions and employing journalists by the thousands. Several new players have emerged including Quartz, Insider, Cheddar, The Information and Axios. The latter, started by founders of Politico and named after the Greek word for “worthy,” launched their newsletter-driven platform with a dramatic manifesto on Medium in 2016:

“All of us left cool, safe jobs to start a new company with this shared belief: Media is broken – and too often a scam. Stories are too long. Or too boring. Websites are a maddening mess. Readers and advertisers alike are too often afterthoughts. They get duped by headlines that don’t deliver and distracted by pop-up nonsense or unworthy clicks. Many now make money selling fake headlines, fake controversies and even fake news.”

What ails other parts of journalism?

Since Axios launched, the problems ailing the news industry have come into even sharper focus. Many news outlets, particularly in the United States, strayed from core principles of fairness, neutrality and fact-based rigour. Instead, some are lulled toward the principles of fundamentalist woke-ism: the notion that journalists should only report news that fits preconceived narratives on racial oppression, gender ideology and anti-capitalism.

In so doing, such outlets are aligning with identity politics or partisan politics and find themselves adrift from early American ideals of free speech, free press, religious freedom and overall pluralism.

President Donald Trump was a lightning rod who channelled some of these forces, speeding up the causes and effects. He attacked the news business and, at times, called it the “enemy of the people.” Some of the mainstream media in turn dropped the gloves and called him a liar in their news pages. And some journalistic institutions on the left are doing the same things they despise in journalistic institutions on the right such as Fox News and Breitbart.

A few lone voices in American journalism, such as publisher Walter Hussman at The Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, continue defending basic journalism principles such as labelling opinion and pursuing objective, fact-based reporting in the news pages. “Americans clearly see too much bias in reporting,” Hussman said in an April speech at The King’s College in NYC, where I chair the journalism programmes. “They also think inaccuracies are either intentional distortions or fabricating news.”

Hussman champions good old-fashioned “objectivity” as one of the core values at his newspaper company, which he believes helps his staff report rigorously in the public interest and which helps his readers trust the newspaper. “It would seem tempting to write a story to convince others to our way of thinking. But that is the very reason reporters need to resist those normal human instincts in order to tell the story as straight as possible, to keep our emotions, prejudices, and politics out of covering the news. Those core values of journalism help us do just that,” he said.

A return to core values?

If a set of factors caused distrust in news – technology disruption, ideological agenda-driven journalism, and an abandonment of core principles – it would be logical to consider those problems while brainstorming solutions.

Already, across the US and world, a host of news media start-ups and associations such as Zenger News, SmartNews and LION Publishers and others are pursuing new approaches to provide quality news. Products such as OpenWeb and the Coral Project aim to improve the experience of comment boards. Companies such as Piano are helping news outlets launch paywalls and grow subscribers. A product I built called VettNews Cx, a division of Vett Inc., is helping news organizations improve their methods for receiving reader feedback and corrections requests.

Indeed, a good starting place for entrepreneurship is to champion some of the core values that caused newspapers to have high trust and impact in past decades. Paul Starr, a Pulitzer-Prize-winning sociologist at Princeton University, wrote about newspapers in a 2009 essay in The New Republic, describing them as, “our eyes on the state, our check on private abuses, our civic alarm systems.”

One problem with Cable TV news in America is an incessant desire to ring the civic alarm system with “Breaking News” banners to the point that the term “Breaking News” becomes meaningless. CNN once used the “Breaking News” banner on a segment about the 102nd anniversary of the sinking of the Titanic. New leadership at CNN this year said they would scale back the use of such banners.

Ultimately, citizens will vote with their feet, their eyeballs and their pocketbooks. Already, many are growing tired of the plethora of content across a range of social media apps and platforms. People, again, seem to echo the poet in Ecclesiastes in chapter 1, verses 8–11:

“All things are wearisome, more than one can say. The eye never has enough of seeing, nor the ear its fill of hearing. What has been will be again, what has been done will be done again; there is nothing new under the sun. Is there anything of which one can say, “Look! This is something new.”?”

Quality information in the future may involve more data, more numbers, more hard logic. It may involve a mix of robots and algorithms working alongside humans to surface rigorous information while telling compelling stories. Ultimately, quality news must help minimize our foolishness and maximize our wisdom.

As we ponder a future for news media in the 21st century, perhaps we should think more about the poet’s words from Ecclesiastes on the role of knowledge and wisdom. In chapter 8, verse 8, he asks, “Who is like the wise? Who knows the explanation of things?”

The Kirby Laing Centre for Public Theology in Cambridge. Charity registered in England and Wales. Charity Number: 1191741

Kirby Laing Centre, Office 1, Unit 6, The New Mill House, Chesterton Mill, French’s Road, Cambridge, CB4 3NP

© 2025 The Kirby Laing Centre for Public Theology in Cambridge