Dave Beldman is a professor at The Missional Training Center in Phoenix, Arizona, and is an Associate Fellow of the KLC.

When the centurion saw what happened, he began to glorify God, saying “This man really was righteous.” All the crowds that had gathered for this spectacle, when they saw what had taken place, went home, striking their chests. But all who knew him, including the women who had followed him from Galilee, stood at a distance, watching these things. (Luke 23:47–49)

While the authors of the Gospels make the focal point of their narratives of Jesus his death (and resurrection), the composition of their rendering of Jesus’ suffering and death includes various spectators.

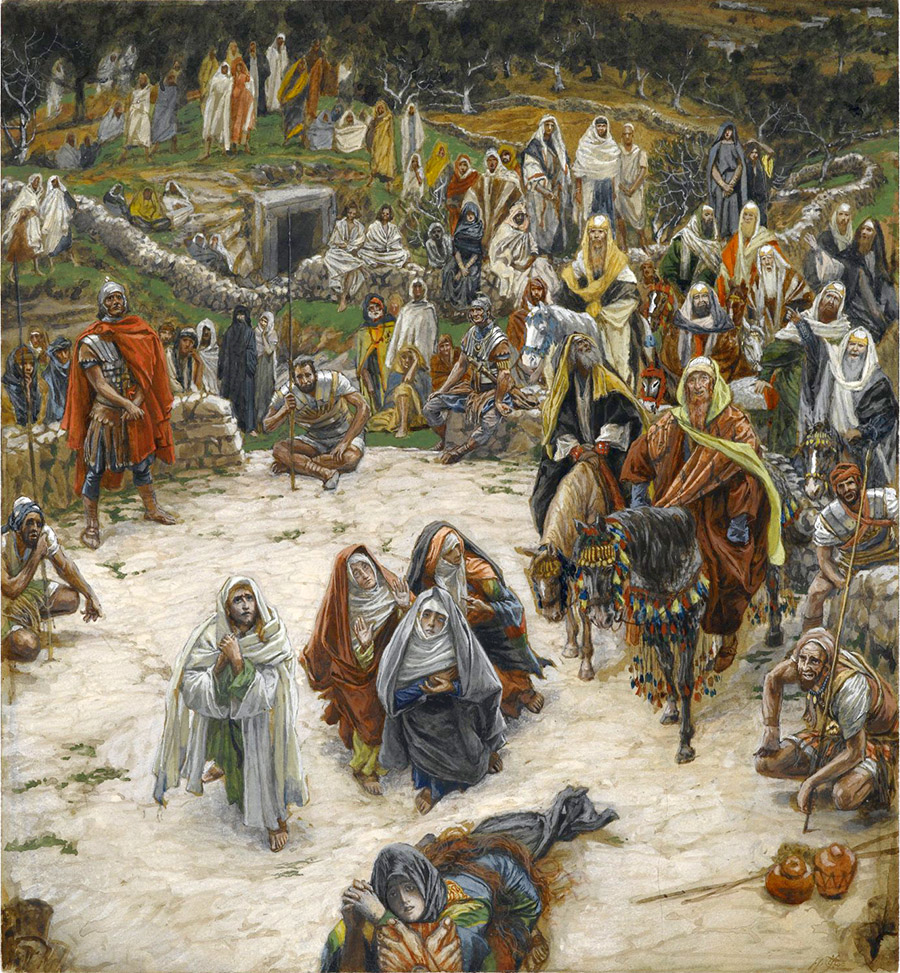

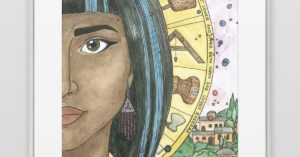

Spectators of Jesus’ crucifixion are the subjects of a recent piece of artwork by artist duo Darren and Trisha Inouye, the creative geniuses behind Giorgiko. Ever since I was introduced to their work, I’ve been intrigued by the fictive world they have created – a world populated by sweet-faced, childlike characters against the backdrop of an ominous, post-apocalyptic-looking landscape. The adorableness of the characters and the bleakness of the landscape are by no means the only contrasts to be found in Giorgiko’s work. We recently met to discuss their painting The Spectacle, the Tragedy, the Passion. Like James Tissot’s work, Gioriko’s portrayal of the spectators is from the perspective of the cross.

Darren and Trisha pointed out that for Christians the day of Jesus’ crucifixion is the most significant day but for others it’s just another day. They understand, as did the authors of the gospel accounts, that there were – and still are – different responses to Jesus’ death, and through this painting, wanted to create hospitable room for people to relate to spectators from different times and places. Anachronism and other types of juxtaposition characterize their artwork and certainly feature in this piece, especially (but not only) in the way the characters are dressed. Styles cross cultures and times, including a Renaissance outfit (with the frilly collar or “ruff”), contemporary skateboarder wear, a nun’s habit and an astronaut suit. Many spectators have their heads uncovered but some don ball caps, turbans, beanies and more (the figure close to the bottom right corner who looks to be a soldier from some era wearing a soldier’s hat/helmet). Characters are both male and female, from different places and times, both modern and classic.

The setting of the painting is also fraught with tension. The marble staircase and column evoke elements of the classical Graeco-Roman architecture of Jesus’ day (though probably not evident in first-century Jerusalem), but the spray-painted graffiti gives it a modern feel. The thick ominous sky and foreboding mountain range in the background might be the most historically accurate part of the painting.

The variety is meant to communicate that no matter who or where or at what time in history you are, you have to reckon with the crucifixion. Although that’s what Darren and Trisha are trying to evoke with this work, they clearly are not trying to dictate how viewers ought to respond. The faces of the people that occupy the world that Giorgiko has created are not easy to read. It’s not accurate to say the faces are blank or emotionless; however, their expressions are extremely muted and only very subtle differences exist from face to face (a slight upturn or downturn of the lip). More is revealed through the postures of the characters (turning to look, staring, not looking at all, peering around others, etc.) but even those are subtle and sometimes ambiguous. For example, I pointed to the two figures who seemed to be shielding their eyes to get a better look, and Trisha asked if the hand to the forehead might not be a salute. The painting invites viewers to engage deeply and reflect thoughtfully.

We talked about some other peculiarities of the piece. The dark-coloured dogs with pointy features and blank white eyes intrigued me. They are the main subjects of some of their past paintings and appear in others. At least six, by my count, make a cameo in The Spectacle, the Tragedy, the Passion. Darren and Trisha explained that in their work the dogs started out more sinister but have developed into a kind of extension (and reflection?) of the human self. Dogs in general (and here in the painting) are human companions – they are typically generous with their love and affection and can bring a sense of peace and joy. In the wrong environment or with the wrong temperament, they can be dangerous, causing fear and violence. The spears and flags are also curiously placed in the composition and are symbolic. Darren described the practice of planting flags – sticking a pole with a bit of fabric on the end into the ground (or the moon!) as an indication of ownership. It’s absurd and futile to think that a planted flag could secure territorial rights. The flags and weapons, for Darren and Trisha, are symbols of human grasping and human pride.

There are further subtleties in the work that make it worthy of detailed study (e.g., beyond its title, there is a clue in the painting that the spectators are indeed looking at the crucifixion). Darren and Trisha honoured me by introducing me to a few of their “friends” (maybe family members) from the world of Giorgiko. The focal point of the painting is the figure in the white T-shirt and baseball cap front and centre, who seems to be in the spotlight. This is Brother who is part of a larger redemption story in the Giorgiko world. Watching from a distance, Wonder and Jay appear perched atop the mountain in the top left corner. And an intriguing character, Judith (blue dress with a white collar), is peering through two people between the columns in the top right. Judith, they explained, has a regrettable history of betraying her friends. In the painting, it’s as though she can’t look away from the crucifixion, but she also doesn’t know what to do with it … should she keep her distance in the shadows or look it fully in the face and in turn have to examine her own broken self. (I caught a sense of hope for Judith from the artists!)

Giorgiko invites us to ponder: What do we do with the crucifixion? Of course, as Christians, Jesus’ death is a world-changing event, but are there ways in which we betray an indifference, a disdain or even ignorance? Here’s a challenge: practise visio divina with The Spectacle, the Tragedy, the Passion. May we be drawn again into the mystery of Christ and look full into the horror and beauty of our Saviour’s death.