Brett Bradshaw is a graduate of Regent College and serves as a director of spiritual formation in Dallas, Texas. He is an Associate Fellow of the Kirby Laing Centre.

For the growing good of the world is partly dependent on unhistoric acts; and that things are not so ill with you and me as they might have been, is half owing to the number who lived faithfully a hidden life, and rest in unvisited tombs.

George Eliot, Middlemarch

The fight for the future of Ukraine wages as I write. I see the gut-wrenching images in the news of men, women and children trapped in the wreckage of war. “That could be me,” I think, “That could be my family.” I read the reports of fierce gun fights and bombings. I watch President Volodymyr Zelenskyy’s impassioned speeches to embolden Ukrainians to defend their country, to embolden the world. I pray.

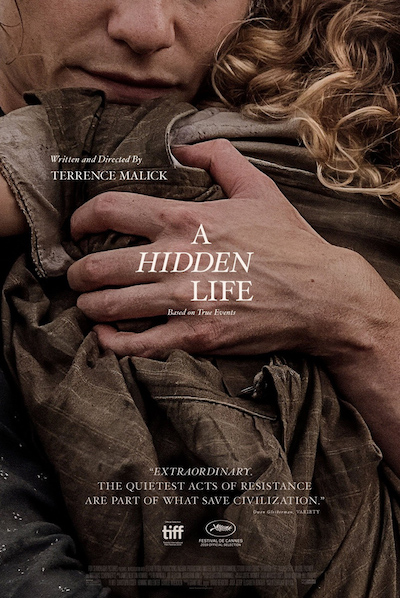

When I first watched Terrence Malick’s film A Hidden Life, I thought it was a masterfully-crafted work of art based on true events in the past. The film portrays the life of Franz Jägerstätter, an Austrian farmer who refused to swear allegiance to Adolph Hitler and fight for the Nazis in WWII due to his faith in Christ. After Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, I now see the film with visionary force for the present. A Hidden Life is a cinematic psalm bearing witness to the never-failing light of Christ in our present darkness.

Terrence Malick employs a cinematic method that calls for contemplation as one would study a psalm lingeringly, patiently waiting for meaning to emerge. A Hidden Life is, I think, a cinematic psalm, a visual poem. Like a Rembrandt painting, the form is a spiritual practice of attention akin to prayer, seeking to illuminate, not entertain, and enter the intersection between “the God who sees me” (Gen 16:13) and human responsibility.

To watch A Hidden Life is to practise seeing with the eyes of the heart. As John Calvin says, “We cannot open our eyes without being compelled to behold Him.” Mountains, streams and fields meet the humble work of Franz and his wife Fanni Jägerstätter’s hands in St Radegund, Austria in 1939. They laugh and labour, play with their three young daughters, and love one another in what appears to be a happily mundane life in an Edenic mountain village. The beauty of creation and the seemingly ordinary of human life converge as symbols of God’s grandeur and intimate presence. A river is shown cascading down a cliff with the distant sound of rushing water. It is a symbol, I think, of the deep mystery of God’s sovereignty and a calling into the depths of human suffering: “Deep calls to deep at the roar of your waterfalls” (Ps 42:7).

The state secretary of the Reich Ministry of Justice Rolan Freisler wrote: “Christianity and we are alike in only one respect: we lay claim to the whole individual.” When faced with the impending call to fight for the Nazis as a loyal subject of the Reich, Franz’s pastor asks, “What are you going to do, Franz? They ask you to take an oath to the Antichrist. Is this here the end of the world? Is this the death of the light?” Franz was a farmer, the sexton (caretaker) of the village church, a devoted husband and father. What did obedience to Christ require of him? What could he do to change the course of the war? Did his actions even matter? Who would care? The film witnesses to the mystery – a knowledge so great it must be revealed – between God’s call of grace and the human response of faith.

Here the example of the Estonian composer Arvo Pärt is resonant. The film employs Pärt’s composition Tabula Rasa: II. Silentium at the height of Franz’s struggle. Pärt composed the music with a method he is known for called tintinnabuli, meaning “bells” in Latin. Each note of the melody “rings”

with a note from a harmonizing chord to resonate a sound for the call of God’s grace and the response of faith. “This is the whole secret of tintinnabuli,” Pärt says in an interview with Arthur Lubow of the New York Times Magazine. “The two lines. One line is who we are, and the other line is who is holding and takes care of us. … the melodic line is our reality, our sin. But the other line is forgiving the sins.” Sound and story pair together in A Hidden Life to ring a bell-like resonance in search of touching the soul.

Reporting for the New York Times from Lviv, Ukraine, Marc Santora’s words demonstrate the power of music: “After seeking shelter while an air raid siren blared, I walked by the Lviv City Council and heard a lovely song, so I stopped to capture a moment of beauty. Then the siren went off again.” Here is a moment where sound became light in the darkness as, I think, Malick searches for through cinema. Once again, A Hidden Life is a work of art that points beyond itself to the never-failing light of Christ in our weary world.

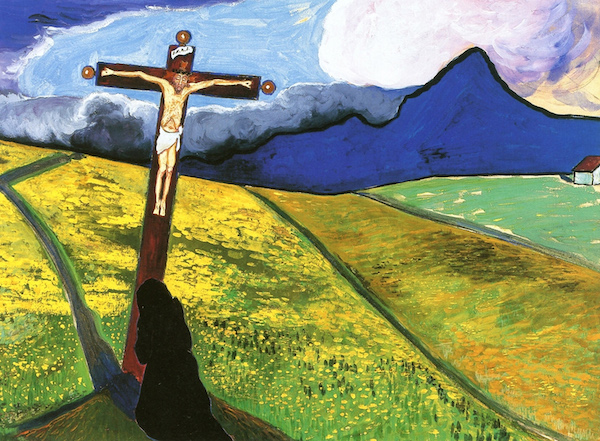

Natural light flickers and flits upon gold foil in Franz’s hands, and the call of discipleship echoes in the words of the church painter:

They imagine that if they lived back in Christ’s time, they wouldn’t have done what the others did. … What we do is just create sympathy; we create admirers. … We don’t create followers. … Christ’s life is a demand. … You don’t want to be reminded of it so we don’t have to see what happens to the truth. … A darker time is coming when men will be more clever. They won’t fight the truth. They’ll just ignore it. … I paint their comfortable Christ. … Someday I’ll paint the true Christ.

Once called up to fight, Franz refuses to swear allegiance to Adolph Hitler. He is imprisoned, tempted, tortured, and finally executed for his conviction “that I cannot do what I believe is wrong.” It was Franz’s fellow prisoner at Tegel, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, who wrote, “When Christ calls a man, he bids him come and die.”

Fanni must also carry the cross of caring for their daughters and working the family farm without the help of her husband. She is rejected and reviled by neighbours and church members. Even so, the film reveals Franz and Fanni united in Christ through prayer, and their marriage becomes, as the Apostle Paul describes, a living mystery of Christ’s love for the church. These are Fanni’s last words to Franz in the film before his death: “I love you. … Whatever you do … whatever comes …

I’m with you … always. … Do what is right.”

On August 9, 1943, Franz Jägerstätter wrote a final letter to his family that read: “I thank our Saviour that I could suffer for him, and may die for him. I trust in his infinite compassion. I trust that God forgives me everything, and will not abandon me in the last hour.” He was executed by guillotine at 4:00 pm that afternoon.

The film shows Franz on a bench as one of three – note three – awaiting their execution, and the scene transforms into a vision. Franz is seen riding a motorcycle on his way home. The sun rises over the mountains. It is a vision of the new heavens and the new earth when the never-failing light of Christ that dawned on the cross and in the resurrection becomes full day. In the final scenes of the film, Fanni’s voice is heard saying:

A time will come when we will know what all this is for … and there will be no mysteries. … We will know why we live. … We’ll come together. … We’ll plant orchards … fields. … We’ll build the land back up. … Franz … I’ll meet you there … in the mountains.

The words are drawn from a vision of the new heavens and new earth in Isaiah 65:17-25.

The camera zooms in on a tree veiled in shadow against the last light of day and lingers for a moment on a mountain river cascading down the cliff: “Then the angel showed me the river of the water of life, bright as crystal, flowing from the throne of God and of the Lamb through the middle of the street of the city; also, on either side of the river, the tree of life …” (Rev 22:1-2). The film portrays the way of suffering love and ends in the comfort of Christ’s return when, “He will wipe away every tear from their eyes, and death shall be no more, neither shall there be mourning, nor crying, nor pain anymore …” (Rev 21:4).

Terrence Malick’s film A Hidden Life cannot stop the war in Ukraine. It cannot ease the pain of human suffering and sin. It cannot tell us exactly what to do in our own time and place. But it does what great art is charged to do. A Hidden Life bears witness to the Way through this veil of tears where a life hidden in Christ with God can become by grace a true sign of the never-failing light that has overcome the darkness.

_________

I owe a debt of gratitude to Park Cities Presbyterian Church and the Faith & Culture ministry for giving me the occasion to contemplate Terrence Malick’s film A Hidden Life. I wish to thank Alan Jacobs and Joel Mayward for their insights into the film that enriched my own reflection. I too want to thank my friend Stephen Bell for introducing me to the work of Terrence Malick.

Get the latest issue in print or subscribe for the next three.