I love motorcycles — especially old motorcycles. It’s hard to explain the attraction to the uninitiated, indifferent or antagonistic, but I suppose it is comparable to some people’s love for cooking, or long-distance running, or crocheting, or woodworking, or gardening or bird-watching. Part of the attraction is aesthetic and mechanical — old motorcycles are rugged and tough but also elegant and beautiful; they are incredibly intricate but also wonderfully simple; they can be somewhat indulgent but also imminently practical.

Another part of the attraction is the immediate (and often unprejudiced) initiation into a fraternity of riders when one makes the decision to kick a leg over a machine and start riding. I have rarely seen the kind of unswerving loyalty and self-sacrificial generosity that I have seen and experienced in the motorcycling community (even in the church which should be the most natural habitat of these virtues). Yet another part of the attraction is a deep commitment to skill/excellence and the cultivation of mind/body/spirit I see at play in the realm of motorcycling. Riding a motorcycle requires the kind of skill and focused attentiveness that is becoming rarer and rarer in our modern, technological society. (1) Riding also has a contemplative dimension, as it requires not only attentiveness but also alone time with nothing but your thoughts bouncing around inside your helmet.

What’s more, I have met geniuses who troubleshoot, repair and restore old motorcycles, and I have met incredible artists who customize and build motorcycles with unparalleled precision and beauty. Perhaps this gives a small window into my love for motorcycles. I want to go a step further and suggest that motorcycles can serve as a vehicle for blessing. To do that, I want to dig into the annals of history; the time: the mid-twentieth century; the place: East London, England.

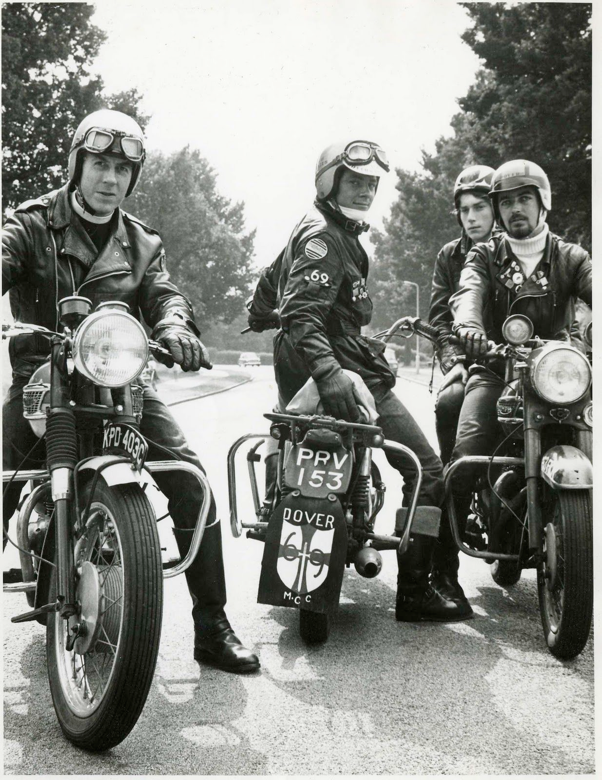

Bill Shergold (1919-2009) was the founder and president of the 59 Club, a motorcycle club established in 1959 for disaffected and socially marginalized youth in north and east London. The club quickly became the largest motorcycle club and even today still boasts some 30,000 members. What may come as a surprise is that Bill Shergold was a priest, and the 59 Club began as a Church of England-based youth club. What made Father Bill’s (the “Biker Priest’s”) ministry to the biker subculture so successful? I would suggest it was a success for at least the following five reasons.

First, Father Bill’s love for motorcycles and the youth was not manufactured but genuine. He had ridden a motorcycle for years before starting the 59 Club and he had a heart for the youth — it seemed only natural to meet these youth where his and their passions intersected. Motorcycle riding and culture was not merely an avenue for evangelism but a good gift from God that Father Bill and the youth of north and east London shared and celebrated.

Second, he could see with clarity that these youth were the kinds of outcasts and marginalized that Jesus no doubt would have pursued in his earthly ministry. From the pen of Father Bill himself:

[Through written correspondence] and above all from the conversations with the boys themselves, I soon began to realize that they were virtually an outcast section of the community. Because of their dress, their noisy bikes and their tendency to move around in gangs, nobody wanted them. Dance halls refused them, bowling alleys told them to go home and change into ordinary clothes. Youth clubs were afraid of them. Even the transport cafes didn’t really welcome their custom (Link Magazine, 1966).

Father Bill had the eyes (and heart) to really see “the boys,” (2) whom the rest of society found distasteful and would have preferred to ignore and in reality did push away.

Third, the 59 Club was interested in its members’ character development — we might say that discipleship was at the heart of the ministry. The history of Christian mission is riddled with “colonial” attempts to “civilize” the “savages,” such that gospel transformation often got confused with social relocation. Father Bill and his colleagues represented the British cultural establishment and “the boys” represented a profoundly anti-establishment culture. The temptation would have been to encourage the youth to toss their black leather jackets, cut their hair, adopt more conventional modes of transport, and “convert” to a socially “acceptable” way of life. The 59 Club (rightfully) resisted this model, in spite of pressure to the contrary. Father Bill and his colleagues effectively removed barriers, providing a bridge between the establishment and the biker subculture, not so that the youth could be converted to the establishment but to provide a context for authentic community and the common good. This did not mean that Father Bill ignored the problematic aspects of the biker culture — “Respect for others, safety and social responsibility were high on his agenda.”(3) Like the very best cross-cultural mission, the 59 Club affirmed the creational goodness of the culture while working against the idolatry in it.

Fourth, the 59 Club encouraged its members to integrate their love of motorcycles with the cultivation of Christian virtues. Father Bill’s dreaded visit to Ace Café is the stuff of legend now. He became convinced that to reach the biker culture he would have to breach its unofficial headquarters, even if it meant being humiliated or worse (he supposed he would probably lose his trousers or get thrown in the canal).(4)

He never expected the warm reception he received from the rough crowd at Ace Café, and the inaugural Biker service at Eton Mission soon after was bustling with youth bikers (and news media representatives). With several motorcycles lined up in the aisles of the church, Father Bill urged his listeners to use their machines as vehicles of blessing — to “dedicate their bikes and themselves to God’s service, endeavouring to use the machines in a responsible way.”(5) Indeed, members of the 59 Club were mobilized, many becoming part of the Volunteer Emergency Service, a nation-wide registry of some 4,000 volunteers. Their unique mode of transport was ideally suited to specific needs (e.g., the quick and nimble delivery of vaccines, medical supplies and blood donations between clinics and hospitals). Not only were the bikers not paid for their service, they had to pay a fee to be on the registry of 24/7 on-call volunteers.

Finally, we cannot underestimate Father Bill’s love for and commitment to Christ and his love for and self-sacrificial service on behalf of “the boys.” Griffiths maintains that this is key: “Perhaps the most effective aspect of his youth ministry came through an absolute dedication to the bikers on a day-to-day offering of pastoral care.”(6) In answer to an intricate theory about the success of his ministry, Father Bill answered simply: “Well that sounds very grand. Actually, I only wanted to show God’s love. [They] were just a nice bunch of boys.”(7)

Father Bill provides a model for cross-cultural, incarnational ministry. He shows us that ministry and mission need not turn us away from our passions but that as we celebrate the wonderful gifts of life (like motorcycles) we might find contexts for participating in Christ’s mission. Father Bill and the 59 Club give us glimpses of the kingdom amidst disaffected youth in post-war British life. They suggest the possibility that even a motorcycle can be a vehicle for divine blessing, that the kingdom can come with the twist of the throttle.