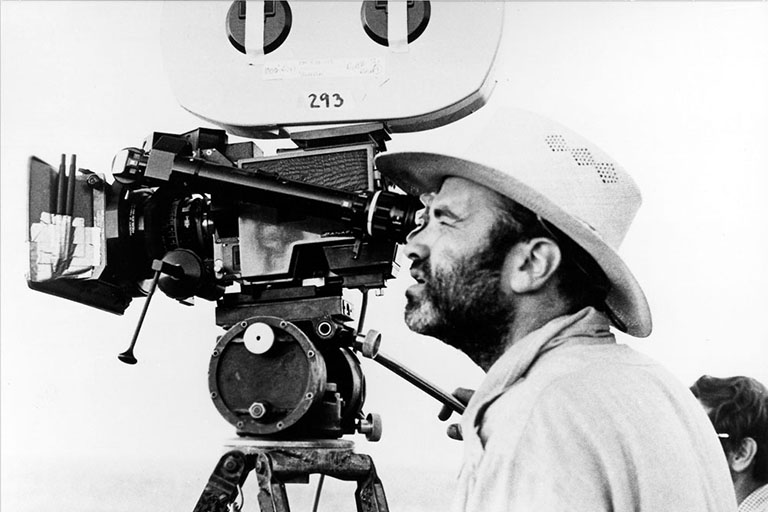

South African writer-director, Christan Barnard, earned his PhD in Industrial Engineering (Stellenbosch University). He pioneered applying machine-learning algorithms to analysing film style, focusing on the silent-sound transition in 1920s cinema and Ingmar Bergman’s work.

Cinema at its mightiest and holiest. A movie you enter, like a cathedral of the senses.

Owen Gleiberman, Variety, on A Hidden Life (Malick, 2019)

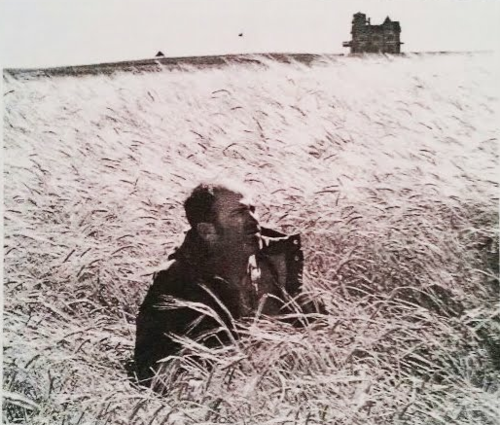

One may be forgiven for not recognising the name Terrence Malick. He is among the great writer-directors in cinema, and nonetheless remains shrouded in mystery. He does not attend the premieres of his films, does not do public interviews, does not attend awards ceremonies and does not allow pictures or videos to be taken on his film sets. He certainly does not have social media. He has been described as being reclusive, unapproachable and taciturn. But for all his avoidance of public attention and the award-ceremony limelight – two standard tools filmmakers use to position themselves as worth knowing and worth working with – Malick remains one of the most sought-after writer-directors in Hollywood, with collaborators including Brad Pitt, Natalie Portman, George Clooney, Jessica Chastain, Sean Penn, Ben Affleck, Cate Blanchett, Christian Bale and Ryan Gosling.

With Malick’s latest film, A Hidden Life (2019) – a seemingly simple story of an Austrian farmer, Franz Jägerstätter, who faces execution for refusing to fight for the Nazis during World War II – the filmmaker once again reminds filmgoers of the unique transcendent power of cinema. It is a film so saturated in beauty and suffering that it assumes a holy quality, while showing the deep humanity of a man and his family in turmoil, agonising to know what the right way to live is in the face of terror. But it is not the content of the story that sets the film apart as cinema at its mightiest and holiest – it is Malick’s singular film style.

Film style

Renowned for his naturalism and an ability to capture moments that seem impossible to script, critics and analysts have approached Malick’s work from auteurist, semiotic, phenomenological, statistical and theological angles in an effort to make sense of the films. Writer-director Christopher Nolan noted that Malick’s style is immediately recognisable but that it remains difficult to describe exactly what it is about the work that makes it so distinct. Which begs the question, how do we define and describe the film style of any particular director?

There is an easy answer to the question of film style and there is an answer with substance. At face value, visual style may be defined in relation to a director’s particular use of camera movements, camera angles, shot scales, colour palettes and cutting patterns. The content may be categorised according to genres or recurrent themes. Along those lines, Malick’s film style is not hard to explain: Shoot on a steadicam, use wide-angle lenses, film in natural light, primarily shoot during golden hour, use extensive poetic voice-over dialogue, posit nature as a protagonist and the man-made machine as an antagonist, and saturate the film in classical and orchestral music. These technical approaches can be imitated to achieve a film style reminiscent of Malick’s, but the spirit will be missing. One may, however, consider the true substance of Malick’s singular mastery of the cinematic form by considering his intentions and methods of creating.

This discussion on Malick hinges on the following premise: Malick has achieved mastery in the cinematic form, implying that he has assimilated the guiding principles (or rules) thereof, and has elevated them to a new plane of application. Essentially, he has written his own set of rules. Concerning the work of auteur directors such as Malick, I propose that the way the artist creates will have an indelible effect on what is created. This article is therefore concerned with a different approach, one that seeks to make sense of the way in which Malick makes films – the mastery he exhibits in his mode of writing and directing – and the effect this has on his film style.

Malick’s rules of filmmaking

The first rule of the film industry is: Don’t be boring. Audiences want to be entertained. End of story. Boring actors and bored audiences cause producers sleepless nights and end directors’ careers. If a young writer-director wants to build a sustainable career, achieving commercial success and keeping mass audiences entertained are imperative. This usually results in original storylines that may have an inkling of artistic integrity being changed to suit the producers’ latest hunch on what audiences want to see. And what audiences “want to see” are predictable storylines where complex characters are flattened to make them more likeable. Any ambiguities are clarified and slow moments in the film are buffered with snappy dialogue, superficial conflict or unmotivated plot twists. Malick, in this regard, chose the road less travelled.

He’s looking for a truthful moment, or an interesting moment. Also for boring moments. For normal moments. He gets what he wants through a very patient, never demanding, questioning and curious way of directing.

August Diehl (on A Hidden Life)

I wanted to remove any distance from the public. It was my secret intention; to make the film experience more concrete, more direct. And, for the audience, I am tempted to say, experience it like a walk in the countryside. You’ll probably be bored or have other things in mind, but perhaps you will be struck, suddenly, by a feeling, by an act, by a unique portrait of nature.

Terrence Malick (on Days of Heaven)

Malick manages to maintain a meandering pace on set that allows for the filming of the ordinary, boring moments. For these moments seem to contain some of the essence of what he is searching for. It is no secret that this meandering pace on set results in films that maintain a similar pace, which polarises audiences. Some hate it, some see something transcendent in it. What remains astounding is that Malick has made film after film in this mode of creation. He has broken the first rule of the commercial film industry, and it has not ended his career.

Very few filmmakers can craft a cinematic experience that, at times, feels more concrete than real life. This difficulty stems, at least in part, from the artificial environment from which most films are birthed – green screens, scenes filmed out of chronological sequence, rushed production schedules, masses of people and machinery crowding the film set. It comes as no surprise that it is a hellish task to create something real by such artificial means, which renders it fascinating that some of the cast on Malick’s The New World (2005) reported that being on set felt more real than returning to their trailers or hotel rooms after the day’s filming had been wrapped. Valerie Pachner, musing on the filming of A Hidden Life, concurs:

During the shoot, we were doing farm work all day. We were actually doing more farm work than acting. This was so wonderful and made it so real.…

It was possible to just be there as a human being.

Valerie Pachner

Small production crews, the use of natural light, and schedules that allow for improvisation and creativity during filming all contribute to the unique atmosphere of a Malick film set. It seems Malick’s ability to craft cinematic moments that strike audiences as vivid, sensory experiences of real life may stem from an ability to work with his collaborators in such a way that the film set – traditionally one of the most artificial and contrived settings conceivable – becomes akin to reality.

Alfred Hitchcock the tormentor, Ingmar Bergman the ticking time bomb, Stanley Kubrick the perfectionist, James Cameron the self-proclaimed king of the world, David Fincher the quiet dictator, Michael Bay the boisterous scourge, William Wyler the prima donna and Otto Perminger the theatrical bully. These are no doubt one-dimensional assessments of these filmmakers, but the fact remains that it is unnerving how commonplace tyrannical traits are among some of the greatest, or at least most commercially successful, directors of all time. This tendency may be explained in light of the hierarchical structures in the film industry, the necessity of a dominant personality to rally an army of crew members, the competence required to navigate the power struggles between creative crew and financiers, and the singular ambition required to rise to the top in a cut-throat industry. This begs the question: Where does the reclusive, or shy, Malick lie on the spectrum between collaborator and tyrant?

He told me to experiment and try anything. And he said, “I will never use any shot that will humiliate you or make you feel bad. You can come to the editing any time you want, and you can take anything you want out of the movie.” In that moment, I felt I could truly try anything – I could shoot without lights, I could make mistakes – and I would have Terry’s support. He is a true artist and a true collaborator.

Emmanuel Lubezki

As an actor, you’re not only there to deliver your lines. You’re also there to create the scenes and you’re invited to come up with ideas. He’s not afraid of letting people take control.

Valerie Pachner

Malick’s genuine collaborative approach stands in contrast to the director-as-tyrant personality that still permeates the contemporary film industry. Malick, who at first seems distant and unapproachable, defies the stereotyped expectations of such a venerable director. His collaborators repeatedly describe him as gentle and humble, a soul seeking answers to life’s ultimate questions. Martin Scorsese tells of a letter he received from Malick after he’d seen Scorsese’s film, Silence (2016), wherein Malick asks, “One comes away wondering what our task in life is. What is it that Christ asks of us?” Evidently, Malick sees a collaborative effort in creating art as a means of exploring these questions.

Malick’s Hidden Life

Malick’s mastery has allowed him to build a decades-long career as a commercially successful director who embraces boredom, his naturalistic approach has allowed him to create vivid, sensory cinematic experiences and his humility and sincerity have allowed him to make true collaborators of his cast and crew. Malick’s mastery of the cinematic form stands as a testimony to his character as a human being. The mystery and ambiguity give way to a man who appears humble and curious: a master in the art of asking pertinent questions and seeking intimate answers through cinema.

For an hour, or for two days, or longer, these films can enable small changes of heart, changes that mean the same thing: to live better and to love more. And even an old movie in poor and beaten condition can give us that. What else is there to ask for?

Terrence Malick (on Days of Heaven)