Dr Jenny Taylor is the KLC Associate Fellow in Journalism and Communication. Her forthcoming book, Saving Journalism: The Rise, Demise and Survival of the News is to be published by Pippa Rann Books.

That the present would not be what it is, were it not for the past seems obvious to popular historian Tom Holland who wrote a now famous book, Dominion, about it. And it should be obvious to Christians too, were it not for the dearth of historical knowledge.

Christians see the world as belonging to God, the creator of the universe, and author of our lives. Thy kingdom come, we pray; but do we know how far we’ve come or what we owe the Bible for so much that we take for granted?

We live in a culture that is now mostly ignorant of the biblical facts of life. We fail to teach the history the Bible gave rise to. Instead, we laud “progress” as though it were self-generating. Instead of resolution, we have progressivism, a politics of nowhere that assumes whatever is new is good. To revile the past and the “dead, white males” associated with it has become a strange social goal. So, it comes as a surprise, even for the historically-minded, to discover just how much of our world was shaped by our Christian forebears, and the Bible that motivated them.

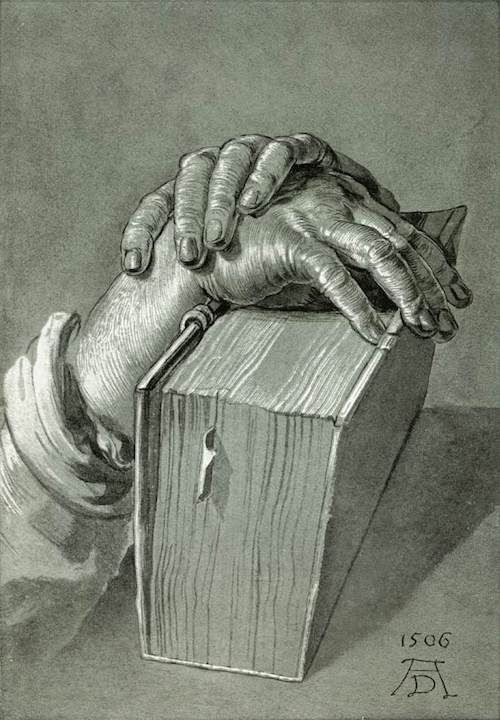

This article forms a companion piece to Estelle Liebenberg-Barkhuizen’s about the production of books. In exploring why early Christians adopted the codex format for their Scriptures and liturgy, that article concluded thus: “… the fact that the early Christians wanted to distinguish their Bibles from texts generated by a secular world, eventually resulted in the wonderful world of printing, binding and reading books.” Pause there and think: the huge labour of books owes its origins to a sacred impulse. One estimate by PricewaterhouseCoopers reckons that the global book industry is today worth about $115 billion.(1) Without the church and its passion for the holy text, we would still be using cumbersome scrolls.

This takes us millennia further back than even the Reformation that ushered in Bible printing, the first mass-produced consumer item. Upon its foundations rose the whole capitalist edifice and the nation state, if Benedict Anderson’s argument in his book, Imagined Communities (London: Verso, 1991), is to be believed. But what is far less well known is much of the work I have been researching: the origins of discourse, and what emerged with it, namely journalism and the political system it spawned.

As a society, we do not accept that our actions have consequences. We have lost a sense of the linkage between our moral and spiritual instincts and the actions and activities that result. We believe we can act as we like, or not act at all, and the world will go on its merry way: That we can act as we like, and the world owes us a living if bad things happen as a result. That’s in part because so many people have been lifted out of grinding poverty and the lack of choices it entails, that we as middle-class citizens rarely need our noses rubbing in the fallout of our own decisions. Yet I meet such people week by week at church: those that have fallen through the cracks into a kind of living hell from which they cannot rescue themselves. They believe the postmodern lie, which is the very air we breathe and tries to convince us that nothing matters.

Their stories are unbelievable, almost unbearable to listen to: of behavioural vagrancy, sexual profligacy, mind-numbing violence and exploitation, degradation of unimaginable voraciousness. And that’s in just one random town. This is the world in which Jesus is at home, thank God, and it should overwhelm us with gratitude to learn from history about how God rescues and blesses, through our use of the Bible, and how it fashions a world in which we might thrive.

My research over the past four years for the book Saving Journalism has had to go right back almost into pre-history to understand the roots of our culture, carried as it is in our discourse. Just for starters: the invention of Hebrew. Seth Sanders sustains the astonishing argument, from previously unmined epigraphic data, that the alphabet was deliberately used not just to transmit royal oracles, as with other scripts, but as “a vehicle of political symbolism and self-representation.”(2) Under the impulse of “something that happened” on Mount Sinai, history, law and prophecy all erupted. Until this moment, no people had been addressed as “you.” Yet here suddenly in the Near Eastern Semitic world, were scribes and prophets developing a written language by which to communicate the very words and thoughts, not of the king, but of God himself to his people. The result is what we have today: the Hebrew Bible, or as we know it, the Old Testament. This research came out in 2009, greeted ecstatically as “a revolution in scholarship.”

Secondly, literary critic Erich Auerbach compounds for us the import of this research with his magnum opus on the power of the narrative contained both within the ancient Hebrew text, and also in the Gospel of Luke. In Mimesis ([New York: Doubleday, 1957], 170), he discusses the representations of reality contained in the stories of Abraham and Peter the fisherman. He takes us on a breathtaking tour d’horizon of classical literature in which he leaves us in no doubt that what we have therein is unique for the future of Western civilization.

Auerbach compares Homer’s handling of the epic story of Odysseus’s return home to the island of Ithaca after two decades of wanderings, with the way the Hebrew Bible’s authors handle the call of Abraham to take his only son Isaac up Mount Moriah and sacrifice him there. Odysseus on his return is exactly the same as he was when he left Ithaca two decades earlier (17). The patriarchs on the other hand have undergone a formation “because God has chosen them to be examples.”

To stress again, this idea of development is “entirely foreign to Homer” or the other writers of antiquity. Such a concept sets up an overwhelming suspense that is not merely stylistic, the artifice of a teller of great legends, but is the very story itself. The absoluteness of this belief – that God is working his purposes out in the very stuff of life of those who attempt to respond to him – gives rise to certain specific literary possibilities unknown before.

One of those possibilities is the mining of lowly character because in it might be contained the purposes of God. There is not the space to go into this in detail, but Peter’s transformation in the courtyard after his betrayal of Jesus, challenged by a lowly serving girl, overturns the extant genres of comedy and tragedy. And it justifies almost the whole of literature thereafter, not least being contemporary reportage and the validation of public opinion.

The form which it was given was one of such immediacy that its like does not exist anywhere else in ancient literature (45). Auerbach believed that no single passage exists in any antique history where direct discourse like that of the servant girl was employed like this – “in a brief, direct dialogue” (46). In short, Peter exists in literature at all because he is loved by Christ, the second person of the Trinity, whose Passion changed the whole world. Reports of it are contained in a book, bound and printed thanks to that same religious impulse.

Language created a people – God’s people; first the Hebrews then the Christians through whom God’s story is worked out. It was not the other way around. People did not simply “create language” for its usefulness. It had not happened, and would not have happened without that religious impulse. And so it has gone on throughout history: that wherever the Bible is translated into the vernacular, there a people is raised up from abjection and ignorance to take its place at the forefront of history. As with the Germans after Luther’s translation of the Bible into the demotic; so with the English after first Wycliffe and then, under Luther’s influence, Tyndale.

In India it was the Northamptonshire cobbler William Carey who gave the common people their own languages in writing and translated their Scriptures so they could think religiously for themselves and work out what was true and what was false. And in China, it was missionaries from London who set up the first printing presses and according to the first republican president, Sun Yat-sen, fathered the Republic with its promise of freedom. “The Republican movement began on the day when Robert Morrison set foot on the soil of China” said missionary-educated Sun Yat-sen with revolutionary optimism.(3) Sadly, the religious impetus that spawned it was regarded as dispensable by first the Confucian intelligentsia who inherited the new world of vernacular literature and newspapers, then the Communist atheists who took over from them. Today China ranks second from bottom out of 180 countries on the World Press Freedom Index.

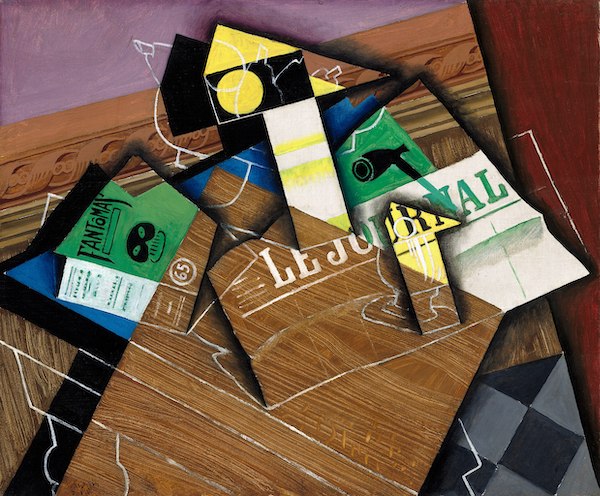

My third point is this: that that same impetus resulted in journalism, the discourse for a people. This was clearly manifest in Europe with the advent of newspapers whose pioneers from Milton to Defoe to William T. Stead were nearly all Christian Dissenters. Newspapers developed on the back of Luther’s Bible and his energetic Reformation pamphleteering. It was Tyndale’s beautiful translation of the New Testament with its remarkable cadences and memorable phrasing that gave Britain a language for ordinary folk. This readied its readers to become the target market for news because it democratised communication.

And on the back of that came oppositional government, dependent as it was on a literate populace. The innovation which oppositional politics rested upon was the creation of “popular opinion” disseminated through newspapers. Whereas politics had so often been subject to demagoguery and sloganeering, rather, this public opinion was directed by the establishment of an independent journalism that knew how to assert itself against the government. It made critical commentary and public opposition against the government “part of the normal state of affairs.”(4) The press in 1792 was for the first time established as an organ genuinely engaged on behalf of the public in critical debate: “as the fourth estate” (Transformations, 60). And this became a model for the world.

It is no coincidence that as Bible reading suffers attrition in the West, so does democracy … and the journalism that it spawned. But that is another story.

Get the latest issue in print or subscribe for the next three.