Peter Altmann is an Associate Fellow of the KLC and is the David Allan Hubbard Associate Professor of Old Testament at Fuller Theological Seminary. He is especially interested in the deep connections between food, economics, and worship.

God as Gardener. Picking up on a common theme in the ancient Near East, rulers – both human and divine – appear in the Old Testament in gardener garb. In this role it was expected that they would protect and work the land so that it could produce its bounty. Along these lines, Genesis 1 depicts God as the one causing all kinds of vegetation, as food for all animals and humans, to spring forth as the ultimate cornucopia throughout the earth. Genesis 2 describes the first humans maintaining a very particular garden, Eden (which means “luxury, bliss” in Hebrew), as God’s stewards. In Ecclesiastes, the king not only made a veritable paradise (2:4–6), but apparently even takes up a plough (5:9), thus developing a deep connection with the place from which his food comes. Outside the biblical texts, the Persian kings that ruled Judea after the exile (538–333 BCE) are rumoured to have only eaten food that came from their kingdom. All this to say, in antiquity a lush and fruitful garden represented the heights of excellence, power, enjoyment, and wealth (cf. Esth 1:5). These gardens were intended to serve as places of delight for all the senses, including the eye (their beauty), the ear (the singing birds; Song 2:12), and especially the mouth and nose through eating and drinking.

The fundamentally agricultural nature of ancient societies like Israel meant that God’s, and human leadership’s, primary responsibility concerned safeguarding crops from enemies and ensuring the necessary ingredients for bellies to become satisfied. God was therefore deeply concerned for the supplies of water, the physical ground, and the plants that grew in it. (These could also serve as striking metaphors for God’s people in Isaiah 5:1–7 or John 15:1–8, not to mention Mary Magdalene taking Jesus for a gardener after his resurrection in John 20:15.)

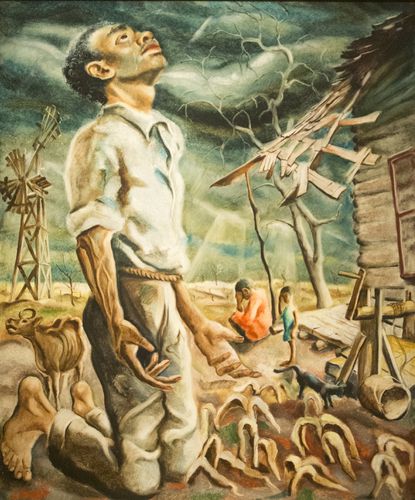

Destruction of Agriculture and Fasting in Joel 1–2. The lush descriptions of, e.g., Genesis 1–2 provide the backdrop for understanding how the desolation of the land, such that it could not provide for its human (and animal) residents, represents a tragedy on many fronts. This destruction marks broken bonds between God, earth, animals, and human worshippers that come to the fore in Joel 1–2. These chapters offer parallel descriptions of the annihilation of the agricultural land belonging to Zion, God’s chosen city of Jerusalem. They describe devastation beyond anything remembered (1:2–4; 2:2). Drought and perhaps wildfires (1:12, 19–20; 2:5), locusts (1:4), and an army as destructive as locusts (1:6), all brought about by God as the leader of the army (2:11), heap up one layer of ruin after another. Thus, rather than gardening and guarding the divinely-elected land, God brings desolation. While it may be tempting to think here of “pruning” in order to keep with the farming imagery, the locust army represents something far more destructive, often associated with the locust plague of Exodus 10:4–20. These events are described in similar ways, especially with the admission, even by pharaoh, of God’s control over them. Nonetheless, just as reported in Exodus 10:19, Joel 2:20 proclaims that God can also drive these bearers of destruction into the seas.

Joel 1–2 show the intricate connection between Jerusalem and Judah’s lands failing to produce their bounty and the dearth of agricultural offerings on Jerusalem’s altar (1:9–10, 16). The food products from Judah’s gardens (and fields) are intended to reach God’s altar. The surprising feature that arises here is that the priests and the land lead the people in lamenting the loss: In v. 9 it is the priests, and in v. 10 the land that already mourn. These two groups seem to have been most sensitive to the divine rejection behind the land’s destruction. In other verses the prophet calls the people to join in – the drunkard who enjoyed the products of the fields (1:5), the farmer who worked with the land to produce them (1:11), and the entire community, both young and old (1:14; 2:16). Likewise, various animals “groan” and “cry out,” augmenting the communal mourning.

Reading these chapters with an eye for “food and place” highlights the integral connection between food-producing land and worship, especially by mentioning Zion along with the priests and the house of the Lord (1:14). This text does not tell us whether the people had done something in particular to bring about this suffering (though the remark in 2:13: “Rend your hearts and not your clothing. Return to the Lord, your God,” suggests some kind of insincere repentance in their past). Its focus, instead, lies on the admonition to carry out a particularly food-related action in response to the devastated land: because the food is “cut off before our eyes” (1:16), the people should proclaim a fast (1:14; 2:15).

That is, because food has been cut off through the devastation of their lands, the people should cut themselves off (further) from food as an act of worship. This action recognizes God’s ability to restore the situation (2:14) by once again providing ample sustenance. There is a profound question mark in the unfolding of 2:14–17: How will God respond? The community’s fast cannot compel God to intervene, but it can display both trust in God’s ability and hope that divine action will ensue. These verses acknowledge a conviction that the human community alone cannot bring about its own deliverance from the desolation of its land. This is a fundamental question on the table in our modern moment with regard to climate change: Can humans invent means to stop (or reverse) climate change? And, even if such technologies emerge (or have already emerged), do humans have the goodness of heart (or will) to use the technologies for the good of all – all humans, animals and plants – that will restore the land, and with it, humanity’s future? Biblical analysis, theological reflection, and the documented inability of nations to hit their emission reduction targets suggest otherwise.

God’s Restorative Intervention. In Joel 2:18–27 God’s own proclamation asserts that divine action will bring their hopes to fulfilment. It is the arousal of God’s own zeal (jealousy) for the land that engenders pity for the people (as well as the land and animals). This mercy overflows into abundant harvests, which indicates healed land. In response, in 2:21–22, it is first the soil that God consoles, followed by the animals. In v. 21, the soil is invited to rejoice, with humans belonging to Zion following its lead in v. 23. The crescendo continues, moving toward feasting and worship of God in v. 26, and reaching a climax in v. 27. Here is God’s proclamation of taking up residence in the midst of Israel. The Lord’s return to Zion, to the temple, is even heralded by the return of bountiful harvests. Luxury or bliss, the “Eden” that the army destroys in 2:3, returns in the physical enjoyment (rather than merely some kind of immaterial rejoicing!) of food and drink (2:23–27). The bonds between God, land, animals and people become whole.

The Kirby Laing Centre for Public Theology in Cambridge. Charity registered in England and Wales. Charity Number: 1191741

Kirby Laing Centre, Office 1, Unit 6, The New Mill House, Chesterton Mill, French’s Road, Cambridge, CB4 3NP

© 2025 The Kirby Laing Centre for Public Theology in Cambridge