Michelle A. Stinson (PhD, University of Bristol) is a Visiting Scholar in the Old Testament at Denver Seminary (Denver, CO) and serves as co-chair of the SBL “Meals in the HB/OT and Its World” programme unit. Her current research considers topics related to food, land care, hope, and the psalms. She is an Associate Fellow of the KLC.

As springtime arrives in the Rocky Mountains and winter wages its tug-of-war with the encroaching summer warmth, gardeners and urban farmers in the Denver area ramp up their hope-filled preparations for what will be the hopelessly short growing season ahead. As a new arrival to this ecosystem – zone 5b on the “USDA Plant Hardiness Zones” map – I continue to marvel at how our mile-high elevation still blesses this would-be gardener with the gift of a window of time, however short, to bask in the glories of growing her own food.

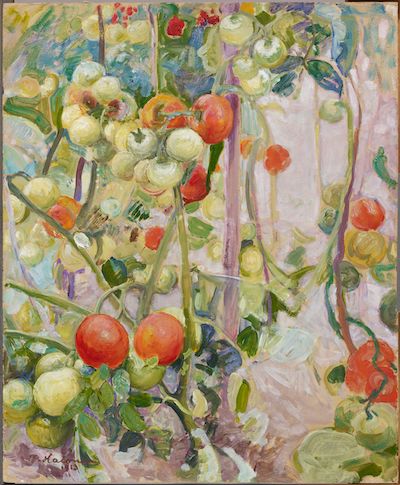

Each year, I make a commitment to myself to refrain from buying tomatoes and peaches during the “off season.” By “off season,” I mean the months before the first ripe tomatoes appear in my garden – early August here in Colorado – and after the last unripe green tomatoes are plucked from the vines before our first frost, some years as early as late September. For peaches, I have to rely on my farmer friends with orchards outside Palisade, Colorado, who bring their bounty to a farmers’ market close to my home. And yet it is a long wait until July for the delight of a PF#1 or an Early Red Haven, the first Colorado peach varieties to come to fruition.

Enjoying the gift of food in season or “in its time” (בעתו) is an idea that has roots in the Hebrew Bible, being present in the garden narrative (Gen 2–3), an undercurrent in the wilderness wanderings (Exodus – Numbers), and something celebrated in the psalms. Psalm 104, a hymn of praise to YHWH, the creator and sustainer of the world, offers a helpful context for considering this theme. For here, the psalmist both celebrates God’s abundant provision while also extolling the wisdom of limits in God’s good creation.

Psalm 104, in keeping with the form of a hymn, is bookended by calls to praise (vv. 1a, 35b). The body of the psalm divides into five stanzas:

The psalmist spends much of the song extolling the works of God, namely, God’s creation of and providential care for the created world and its inhabitants. Surprising to some readers, human beings don’t enter the psalm until v. 14, almost halfway through the composition. As scholar James Mays notes (in Psalms, IBS [Louisville, KY: John Knox, 1994], 334): “It is remarkable with what unqualified directness the human species is considered as simply one of the creatures dependent on the providing of God.” While humans may seem to appear “late to the party” of this psalm, they still – as we shall see – have a seat at the table.

In Psalm 104, abundance and limitations are held in a beautiful balance. In this hymn that celebrates the abundance of God’s provision for – and through – the natural world, the psalmist also describes and celebrates the specific limits and boundaries embedded within the created order: namely, “an appointed place”/ “boundary” (גבול/מקום) set for the waters (vv. 8–9), the “appointed places/times” (מועדים) set for the moon and the sun (v. 19), and God’s provision of food “in its time” (בעתו) for God’s creatures (v. 27).

In the centre section of the hymn, the psalmist praises God’s work in providing food appropriate to various creatures. God causes grass to grow for the livestock (v. 14a) and various plants for humans to cultivate and transform into food (v. 14b). The psalmist pauses to delight at the possibilities humans are invited to enjoy: “wine to gladden the human heart, oil to make the face shine, and bread to strengthen the human heart” (v. 15). (2) It is not surprising to hear of these three food products – wine, oil, bread – within this psalm since they are derived from what scholars refer to as the “Mediterranean triad” (grapes, olives, grains), the three agricultural crops that grew most easily in the semi-arid landscapes of ancient Israel.

The theme of food is picked up again near the end of the song as the psalmist now considers God’s food provisions for all God’s creatures – the land creatures and the sea creatures and God’s human creatures – all who benefit from the largesse of God’s generous hand: “These all look to you to give them their food in due season. When you give it to them, they gather it up; you open your hand, they are filled with good things” (vv. 27–28). Here the phrase translated “in due season” is literally, “in its time” (בעתו; cf. Ps 145:15).

This phrase, occurring fifteen times in the OT, refers to “a time set by nature (i.e., for rain or fruit) or the right moment for something,” be this the rains, harvest, fruit, food, day and night, constellations, God’s intervention, or a word. (3)

As the psalmist contemplates the generosity of God, there is also an acknowledgement of the natural limits imposed by seasonality in God’s provision in and through the natural world.

Reflecting on my lived reality of hoping and waiting – and at times not so patiently waiting – for my first taste of summer tomatoes and peaches, it is easy to be tempted in late February by the allure of the beautifully sun-streaked peaches on display in the produce section of my local grocery. And yet I know that one bite will reveal the true nature of that fruit. It was pulled from a tree in the southern hemisphere and allowed to “ripen” in a cargo container, while being transported across the waters. All this in order to appear as an impossible-possibility in the midst of winter’s stranglehold on the landscape. Like the fruit in the primordial Garden, one taste makes everything clear. And yet, as Psalm 104 reminds us, fruit – enjoyed in season – holds within itself the goodness that it, and we, were created for.