Craig Bartholomew is the Director of the Kirby Laing Centre. Istine Rodseth Swart is an administrator and the Associate Editor of The Big Picture.

Craig Muses

It’s a new notebook, fresh and pristine, well crafted. Opened, the spine sits flush against the desk, just as it was made to do. As the thoughts come, the fountain pen glides across the smooth-textured paper. Ordinary glory.

All workmen know that doing a job well requires quality tools. This goes for the student, the scholar, the writer, the artist, the administrator, as much as any other worker. Good painters know the difference between a good brush and a bad one, between quality paint and cheap, inferior paint. Workers feels bereft and inadequate without their tools. Good work involves far more than the right tools, but the right tools provide the confidence and context for good work to be done. It is the same for the writer.

Writers’ tools have changed dramatically over the last 35 years with the communications revolution: computers, software and keyboards now take pride of place, displacing the pen and the notebook. We doubt, however, that the pen and notebook will become redundant. Most of us move relatively seamlessly between the notebook and the computer. They are very different mediums, and we do well to retain their complementarity. When in a supermarket, I make sure to walk past the stationery section even though I am fairly sure that there will be nothing there to attract my attention. I am somehow drawn to the tools of my vocation. I am called literally to be a writer. But writing is an indispensable part of many vocations, and in this respect the same rules apply.

It is the notebook and the pen – stationery – that is the focus of this article. Not just any tools provide the writer with the confidence and context for good work. Alas, having outsourced most of our industrial base to China and other countries, we welcome back with open arms a tsunami of cheap, disposable, poor quality stationery. We all know that plastic is polluting our oceans and rivers, but again and again we buy and dispose of cheap plastic pens and other stationery. Perhaps this is just the price of progress, but I think not.

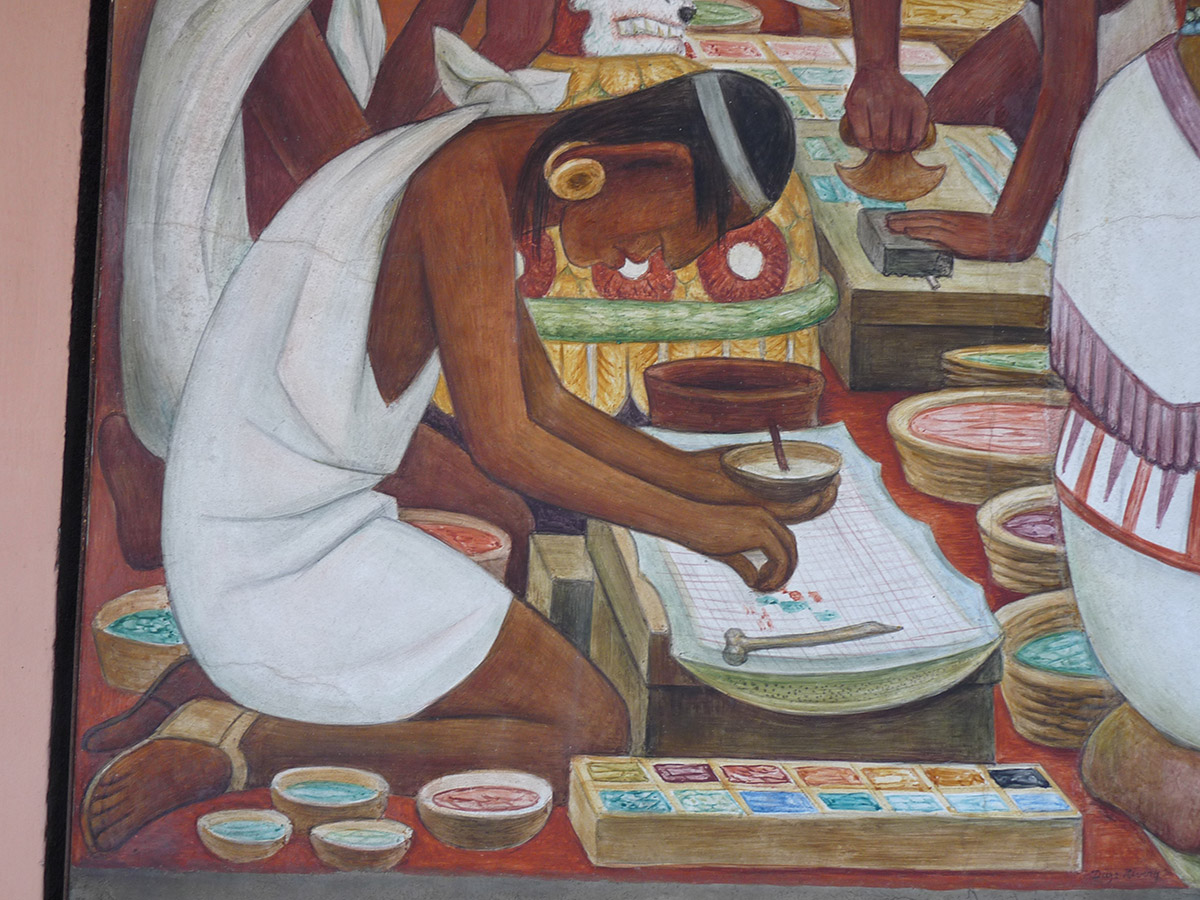

I learnt from Calvin Seerveld that cultural implements like the pen did not have to develop the way they have. Even as humans open up the hidden potentials of the creation, we make choices to go one way rather than another, some far better than others. The ubiquitous plastic, disposable pen serves neither the environment nor the writer well. No writer wants their hard-won work to be hastily received and then quickly disposed of, so why use blunt tools that exude such an ethos? Although there is something endearing and nostalgic about the quill in Harry Potter, we need not go that far back to find the tools we need!

I am an advocate of the fountain pen. Invented in 1827 by the Romanian Petrache Poenaru, he described it as a “self-fuelling endless portable quill with ink.” A good fountain pen – I have 2 Lamys (https://www.lamy.com) – can last a lifetime and be handed on from generation to generation. And one can easily avoid plastic cartridges with what is nowadays called a “converter.” Quality inks come in a variety of colours which make a welcome change from plastic highlighters.

I am an advocate of the fountain pen. Invented in 1827 by the Romanian Petrache Poenaru, he described it as a “self-fuelling endless portable quill with ink.” A good fountain pen – I have 2 Lamys (https://www.lamy.com) – can last a lifetime and be handed on from generation to generation. And one can easily avoid plastic cartridges with what is nowadays called a “converter.” Quality inks come in a variety of colours which make a welcome change from plastic highlighters.

The ballpoint pen replaced the fountain pen in the mid-twentieth century, but I have yet to find one that reaches the quality of a good fountain pen, and there is a big difference between a good ballpoint pen and cheap disposable pens. As our societies seek to remain connected with the world, we are amidst something of a return to analogue and a revival of classic stationery. Alas, no sooner does the fountain pen make a return, than our consumer culture mass produces it. Near where I live, one can buy one today for £2.

So, what sort of tools do we find best for our work? I love Clairefontaine products, made in France (https://www.clairefontaine.com). Even their relatively cheap, stapled notebooks easily open flush to the desk and are a delight to write on. The difference is tangible.

Istine reminisces

At age nine I had to change schools, quickly discovering that my old one was unusual,[1] at least for teaching Marion Richardson handwriting. Suddenly expected to handle a dipping pen and write in cursive style, my first attempts were deplorable. My teacher, short of stature but ferocious, declaimed: “What have we here? A BLOT!” The comment seemed unrelated to the splotch in my workbook – the shy, timid new girl with the impossible name was now a blot.

Fortunately, my deep-seated love for pen and paper carried me through the feared dipping pen to the beloved fountain pen with its slight, satisfying resistance on well-made paper. In addition, my mother was a teacher and demonstrated that teachers are fallibly human, thus helping me to accept that I was not a blot on creation. It took a while though, and profoundly affected my treatment of pupils and students when I taught. Alas, my rocky road to penmanship inhibited the development of beautiful handwriting, but did not diminish my admiration for a skilled hand, or the breathtaking art of calligraphy.

Most teachers love stationery. As HOD, I was heartened to see how the almost ceremonial handing out of departmental stationery supplies helped combat beginning-of-the-year blues. Careful budgeting ensured that every teacher received at least one favoured item and each one’s order was checked with almost childlike joy, augmented by discovering new suppliers who could consistently provide violet whiteboard markers: apparently, mysteriously, an essential requirement for our mathematics teachers.

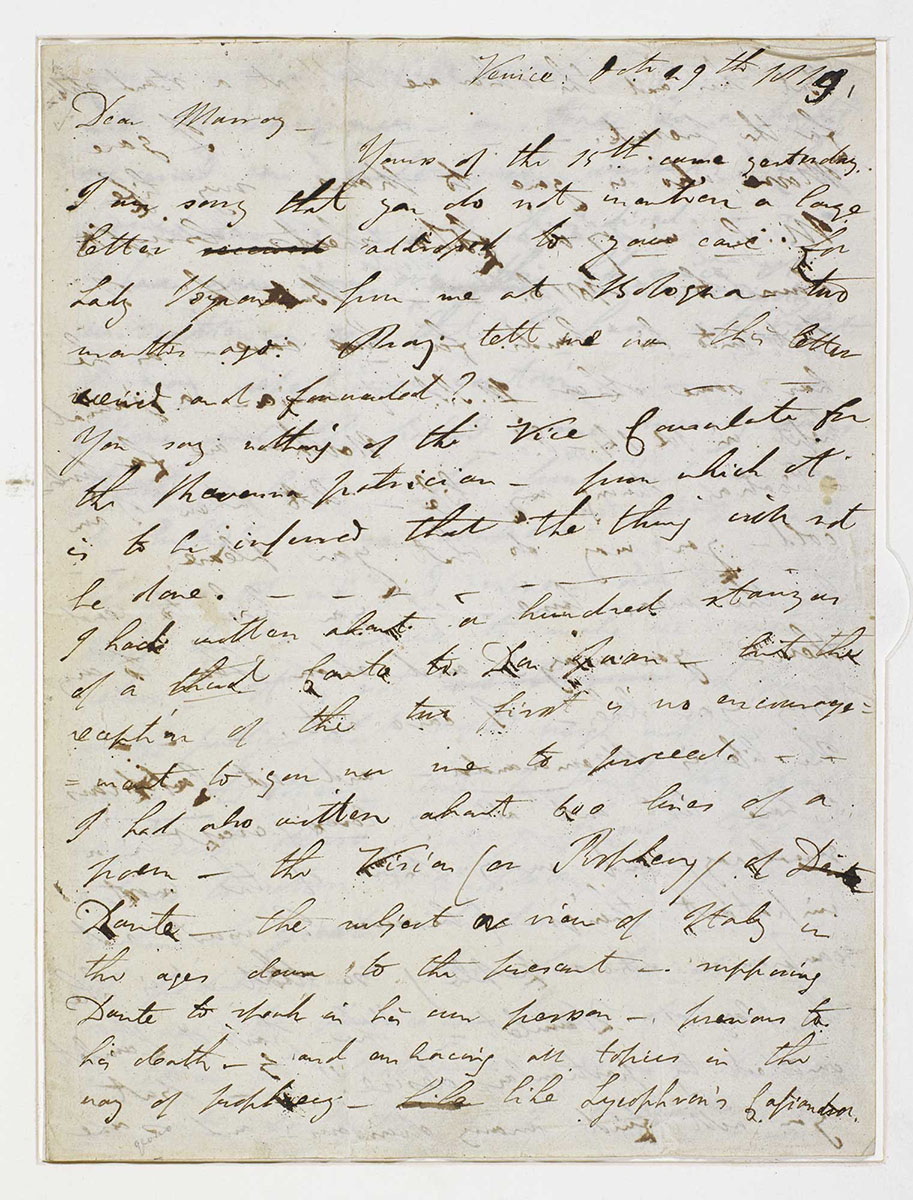

I lament the demise of letter writing: recognizing senders by handwriting; excitedly examining foreign stamps; deciphering closely written, space-maximizing script of “airmail letters”; experiencing the thrill of handling beautiful, thick, creamy paper, sometimes precious handmade paper; the joy of receiving thoughtfully purchased or painstakingly hand-crafted cards.

Modern stationery and modes of communication have not only robbed us of quality, but also motor skills and thoughtful social interaction. Computers allow us to cut, paste and delete to near-perfection, but at the cost of developing skills of planning and structuring before writing; pausing and thinking while writing, accepting imperfections and imbuing communication with character.

Our love of books, paper and the ingenious implements with which we make marks on them, remind us that we enjoy creation not only through the works of God’s hands, but also through what is crafted by the hands of his creatures.

Resources

Although surprisingly little has been written about this ubiquitous dimension of our lives, here are some sources:

***

[1]. The school I left was located in Isipingo Beach, unusual for being the only South African town from which whites were evicted under the apartheid regime’s group areas act.