Titia Ballot, who was born Titia du Toit, is an acclaimed South African artist whose ancestors were French Huguenots. Istine Rodseth Swart talks to her about her roots, faith and artworks.

IRS: Titia, you lectured at the Potchefstroom University for Christian Higher Education (PU for CHE) from 1986 to 1991 when Craig Bartholomew and his Christian Worldview Network were active in the RSA. What was your involvement with the CWN at that time?

TB: At the time I headed the Fine Arts department at the then PU for CHE, where lecturers were expected to express a Christian worldview in their fields of expertise. Today it is known as the North-West University, an amalgamation of three institutions.

The Fine Arts department and the History of Art department, headed by Prof Muller Ballot, endeavoured to establish a forum for Christian Aesthetics by involving other departments e.g., philosophy, theology, music, drama and the Institute for Reformational Studies. A series of conferences took place with participants from abroad as well as local artists and academics. As a result of these conferences, we met Craig Bartholomew and learned about his Christian Worldview Network. We then collaborated in preparing a Manifesto for Christian Artists which was published in 1994 by the research committee of the Arts Faculty at the PU for CHE. In 1994 both Art departments were closed due to the university’s rationalisation programme. This ended my academic career and necessitated our move to Stellenbosch where Muller was appointed as director of the University Museum in 1990.

How wonderful it is to see how God blessed the endeavours of many over many years, eventually to come to fruition in the Kirby Laing Centre for Public Theology. My involvement, although with interruptions, in realising this ideal has enriched my worldview which finds expression in my art.

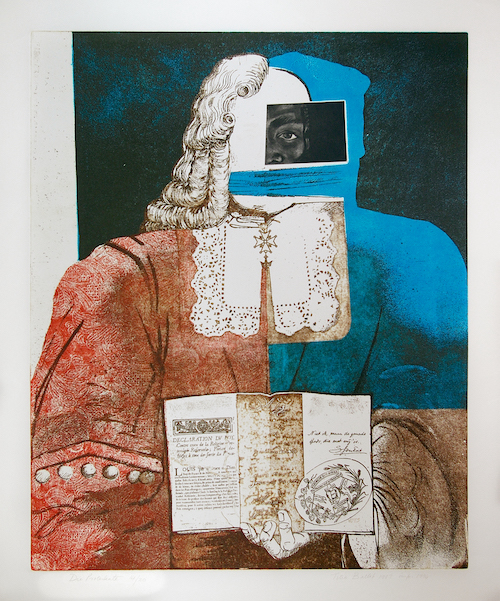

IRS: The Protestant, your etching created in 1987, is now the centrepiece of the permanent collection in the Heritage Room of the Huguenot Memorial Museum, in Franschhoek (South Africa), that aims to portray the legacy of the Huguenots with more honesty than the political climate in the country allowed in the late 1980s. Tell us the story of the origin of the etching, its “rediscovery” and the exhibition of which it is the heart.

TB: A member of the du Toit clan donated it to the museum. During the museum’s rejuvenation in 2019, it was discovered and chosen to embody the contribution of all Huguenot descendants in South Africa: It is at the centre of a wall of portraits of famous and ordinary descendants of different race groups. Twenty-two years after it was created the portrait’s message of hope for reconciliation in our land is being understood by a new generation of South Africans. For the first time the new exhibition now places the Huguenots of South Africa in context to the massive global flight out of France during the 17th century.

IRS: What is the significance of the enigmatic black man superimposed onto the face of the refugee in the portrait?

TB: Two years before the first group of 320 Huguenots – French refugees – arrived, the brothers Francois and Guillaume du Toit from Lille, made their way to the Cape. They received free passage on VOC ships, a sum of money, and were granted farms near Stellenbosch and in Paarl. They were issued with the necessary implements, seed, building materials and animals (eventually to be paid back to the Company). They worked hard and prospered. Guillaume had only daughters, making Francois the father of the du Toit clan in South Africa.

When in 1987 during the “struggle years” I met a young black pastor and activist for human rights named Francois du Toit, it cemented my belief in the existence of a heritage of protesting Protestants in South Africa. More importantly, this descendant and namesake was a fellow Christian, also protesting against the injustice of the apartheid regime. This is the origin of the African head. The message of Christians of all races combatting injustices together wherever and whenever it occurs is what prompted the Huguenot Museum to choose this work as centrepiece. The current influx of refugees to South Africa makes the work even more relevant for our time.

IRS: What is the significance of the documents the refugee is holding?

TB: 1669: A proclamation by Louis XIV regarding the fate awaiting the Protestant refugees should they flee: confiscation of property, access to education and professions revoked, banishment as galley slaves, etc.

1706: A letter of complaint to the Lords 17 in Holland signed by Adam Tas and 31 Huguenots (including the du Toit brothers) exposing the corrupt farming practices of Governor Willem Adriaan van der Stel, resulting in his removal from office. An act of protest against injustice for which they were incarcerated.

1875: About 170 years later, Dominee S.J. du Toit, a direct descendant of Francois, established an organisation in Paarl to fight for the recognition of Afrikaans as a written and official language alongside Dutch and English at the Cape. Shown is the Emblem of Die Genootskap van Regte Afrikaners as well as a sentence in his handwriting stating: “Niet ik, maar de genade God’s die met mij is.” (Not I, but the grace of God that is with me.)

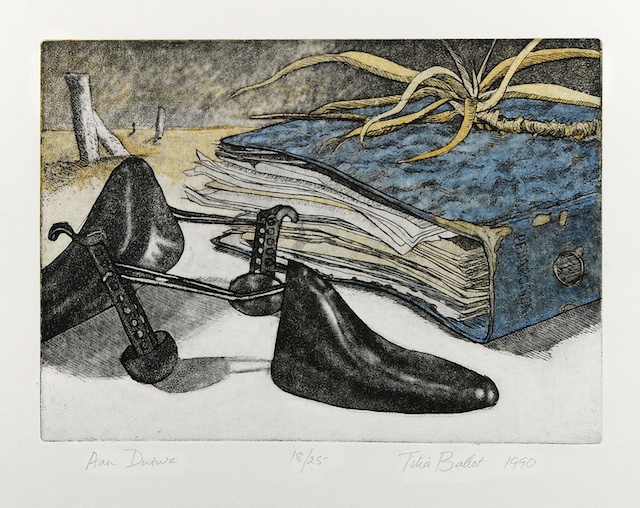

IRS: Your delightful For Dutwa, is a reference to your father that suggests that your parents made you aware of your roots. What other valuable lessons did you learn from your family?

TB: Other valuable lessons, as alluded to in this etching, were a love for learning and respect for nature. We also knew that their footsteps were safe to follow. My parents and grandparents were believers so I grew up knowing about the Trinity. However, it was only during my time at high school in the fifties that I made a personal commitment to follow in His footsteps. It was during the sixties that our family began to doubt the “good intentions” of the apartheid leaders. Through our involvement in the work of the Moral Re-Armament group in South Africa we were able to meet with citizens of other races in our home or in theirs. This was very unusual for Afrikaner families at the time. I therefore knew that apartheid was incompatible with a Christian worldview and that I needed to do something about it.

IRS: What are some of the complexities of your ancestry that influence your work?

TB: I honour my ancestors because of the decisions they made in faith and obedience to God. They chose the Protestant way in spite of severe persecution and they chose Africa although there were other options, less foreign and less dangerous. I firmly believe that the reformed faith they brought still enables us today to rebuild the bridges they and their descendants destroyed and that our faith is the only bridge we have to reach out to our estranged fellow South Africans.

However, I still struggle to come to terms with the fact that the descendants of Huguenot and other settlers were responsible for the apartheid regime’s atrocities and injustices in SA as were exposed by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission – the TRC – (1995 – 2002). That descendants of a people driven from their homeland in 1688, could so soon start to “forcefully remove” fellow South African citizens from their land, is difficult to fathom.

IRS: In 2008 you were honoured with a prestigious award from the South African Academy for Science and the Arts with the following (translated) citation: Titia Ballot is virtually the only South African graphic artist that stood out boldly in the spotlight with her Christian-based message of reconciliation and healing.

How have your spiritual journey and your artistic development informed each other?

TB: Muller and I were married in 1968 and lived in Potchefstroom where we both lectured at PU for CHO. In 1980 Muller was seconded to be our cultural attaché in Bonn, Germany, for four years. It was there, seeing my country from a different viewpoint and being better informed about its politics, that I fully realized the evil of the apartheid regime. We returned to the university in 1985, resolved to try to bridge the social alienation in our Christian community caused by apartheid. We joined Koinonia, a local nonracial group of Christians and met regularly in spite of the political implications at the time. It was at such a gathering that I met the black pastor who features as a protesting Protestant in my etching.

After Germany I felt like a stranger in my own country but knew that I was more African than European. I needed to express this in my art, returning first to my roots, to Clocolan in the Free State where I was born on the border with Lesotho. Second, feeling like a refugee in a strange land, I researched my Huguenot ancestors with whom I now felt a kinship. I realized that apartheid has robbed South Africans of our trust in one another and that we needed to get to know each other again. I felt a need to share my culture with that of all South Africans in order for me to absorb their rich and diverse cultural heritages as well.

The first works were a series of still lifes in the style of the 17th century Dutch “vanitas” paintings which were inspired by Ecclesiastics 1:2: “Everything is meaningless, utterly meaningless.” These paintings, depicting hoarded valuables, were meant to warn the affluent against greed and to remind them of the reality of death. By grouping objects with cultural meaning from various cultures in SA together, I intended to reach out and to heal. This theme of sharing and appreciating other cultures continued to appear in my later work.

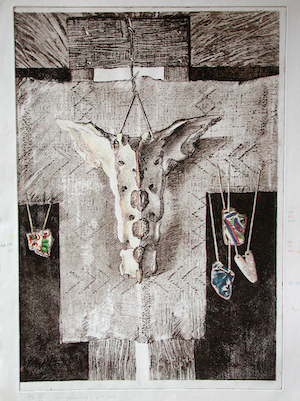

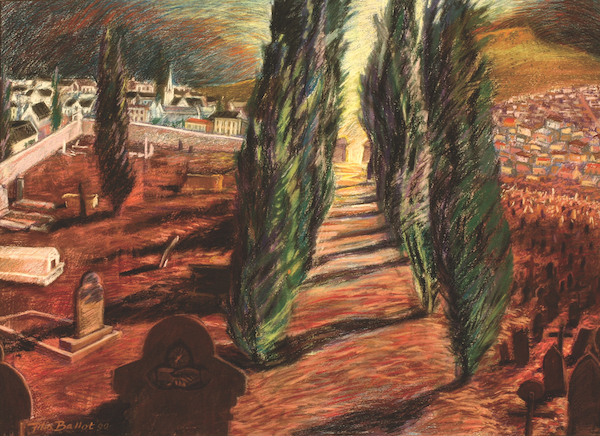

From 1988 to 1994 my pastel paintings in large format expressed my anger and frustration at the lack of change and the government’s inability to make decisions. Works like Good Friday in Graaff-Reinet and The Bartholomew-night massacre and other Fears speak to the injustices, historical and current, as well as the fears prevalent in our society. Etchings such as Cross for the Cape of Good Hope express the fears and uncertainty felt before the dawn of a new democratic SA. The cross appears in a number of my works in different guises as a symbol of salvation and of our only hope for a better future.

During the 1998 sessions of the TRC (some of which I attended) I was confronted by the skeletons in my ancestral closet. My way of coming to terms with it resulted in a series of four etchings where I deconstructed the Voortrekker Monument, a symbol of my Afrikaner heritage now proven to be tarnished and shattered. As signs of hope and redemption I included either water or fire as symbols of restitution and of the hope to be forgiven by those we trespassed against.

IRS: How would you distinguish between spiritual art and Christian art?

TB: Spiritual Art I see as an umbrella term for all art expressing religious ideas and corresponding worldviews. Thus, Christian art is also spiritual art.

IRS: Would you describe your work in general as spiritual or specifically Christian?

TB: I consider my artwork as specifically Christian because I see the world through a Christian lens. I realized early in my life that creativity is His special gift and I should use it to the best of my ability and as my way to thank and praise Him. My art is the visual language of my faith whether people understand it as such or not. My art is addressed to all viewers and not specifically to Christians. My work is not created to be used in churches but works have often been exhibited there confirming that Christian artists too have a calling to fulfil in the secular world.

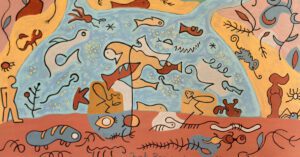

Examples of works that have been labelled as spiritual are the Transcendental Elements of Air, Water, Earth and Fire featuring no specific Christian symbols, although I had the burning bush in mind. The Genesis series (the seven days of creation) is another example. Good Friday in Graaff-Reinet seems to be just a landscape, until you become aware of the centrally placed cross disguised as a pathway as well as suggestions of injustices in this town. Good Friday, when Heaven came to earth to save mankind, has inspired several artworks through the years.

In my visual language I often use symbols and metaphors as keys to understanding the meaning. Biblical references, history, art history in particular, politics and literature all feature in my work.

IRS: What did you intend to convey with Triptych for the Promised Land (parts of which are also seen in Self-portrait with Muse)? What are its most significant symbols and references?

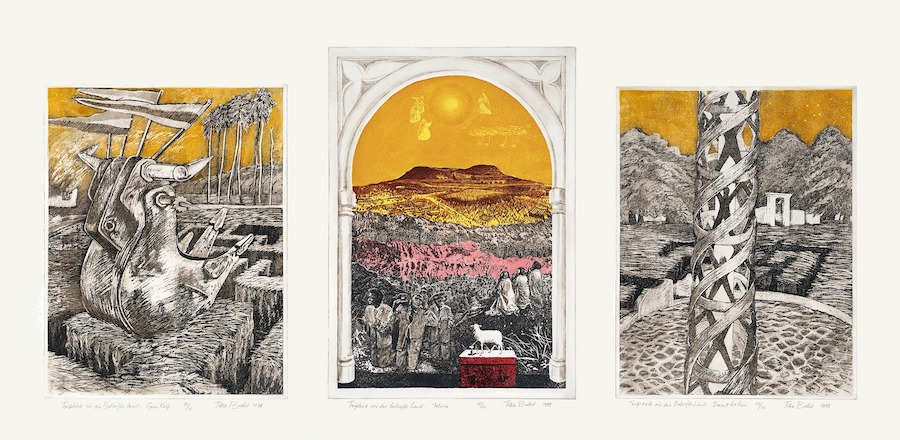

TB: Triptych for the Promised Land, comprising the panels Golden Calf (1994), Moria (1998) and Column of Fire (1994) is a prayer for the new democratic RSA.

Life on a cultural boundary has long been a theme in my work. In this triptych references to the Gent Altarpiece, painted by the Van Eyck brothers in 1453, are interwoven with images of the annual Easter mass congregation of the Zionist Christian Church of Africa at Moria near Polokwane. The parallel drawn is that of Israel’s biblical journey to Canaan and the South African experience of being en route to a promised land – a free and democratic South Africa. Moria, the centrepiece, with its parked buses, uniformed ZCC worshippers and angels flying alongside helicopters bearing the new national flag, contribute to this festive “Adoration of the Lamb” in Africa. Moria, being the biblical site where God provided a lamb to be sacrificed instead of Isaac, Abraham’s son, becomes more meaningful because it foreshadows Jesus’ redemptive death on the cross.

The lamb: This work was completed during the years when the TRC held its hearings throughout the land in an attempt to confront the past and effect reconciliation and healing for all South Africans. I have always believed that the only way to healing was through the cross and that believers know The Way. At the 1998 Easter Z.C.C. gathering, TV footage showed three political figures kneeling and praying together: Mandela, de Klerk and Buthelezi. They represented vastly different cultures and ideologies but prayed together nevertheless. This to me was a sign of hope and proof that the Lamb is truly our only hope of salvation.

The golden calf on the left appears to be a destructive metal monster as a symbol of a violent past and/or of the violence inherent in humankind. It tears up the land against a background of burning houses and crops.

The column of fire on the right depicts a tranquil pond and a column of light around which human figures are standing on each other’s shoulders whilst clasping hands; a promised land only to be entered after forty years of wandering in the desert in order to learn obedience to God’s word? In contrast to Golden Calf, Column of Fire suggests a constructive participation in the rebuilding of the land and the healing of its people.

IRS: To return to The Protestant: Not every artwork produced by a Christian artist has an overt Christian message – is there anything specifically Christian that this work conveys?

TB: On the third document in the refugee’s hand there are the handwritten Dutch words of Dominee S.J. du Toit, mentioned earlier. The document of Louis the 14th specifically refers to Christians of the reformed faith. There is also the well-known Huguenot cross on his chest.

IRS: As you reach your milestone 80th birthday this year, what are your plans for the future?

TB: It is now time to take stock, to make sense of all the work done during the past five decades. I am therefore compiling notes, images and articles about my work for a publication sometime in the near future.

Being in the winter of my life, I experience time and place anew having a broader overview of time past as well as a sense of time future while also savouring the present. I am deeply grateful for the blessed life I have been granted.

Visit Titia’s website: www.titiaballot.com for more information about the artist and to see the works referred to, but not illustrated, in the text.