Jamie Myrose is a doctoral student studying Systematic Theology at Boston University.

The inflation rate in America hit a generational high of seven percent in December, 2021. It is unsurprising, then, that many

Americans have turned to “side gigs” to help make ends meet. Pandemic layoffs and furloughs made this market more prevalent as people found themselves at home for long stretches of time without work. Any interest or hobby could become an opportunity to make a few extra bucks.

Side gigs, however, are not a result of the pandemic alone. In a capitalist economy, the demand for higher profits results in the pressure to monetize every hour and activity. This pressure means that hobbies are no longer just hobbies: they can (and should) be monetized to help one’s bottom line. Recreational activities gain a secondary purpose as forms of pseudo-employment, often leading to anxieties concerning one’s skill level. Being an amateur at an activity, which was previously fine for one’s personal use, may now keep someone from being contracted. The worth of pursuing an activity becomes associated with its potential to produce income rather than for the love of the activity alone, an external rather than internal validation.

In 1 Corinthians 9, St Paul asks if ministers have the right to receive compensation for their work. Should the church in Corinth support his activity there, or should he seek out alternative employment to perform simultaneously? Though he ultimately chooses not to exercise this right, Paul answers his question with the former: as with any trade, ministers should be compensated for their work. Yet our modern, capitalist context invites the inverse of this question: does one have the duty to make a living off of one’s talents or skills? To what extent can talents remain just talents, distinct from the work of our livelihoods? Must they be monetized? Tales like The Juggler of Our Lady offer an insight to this question.

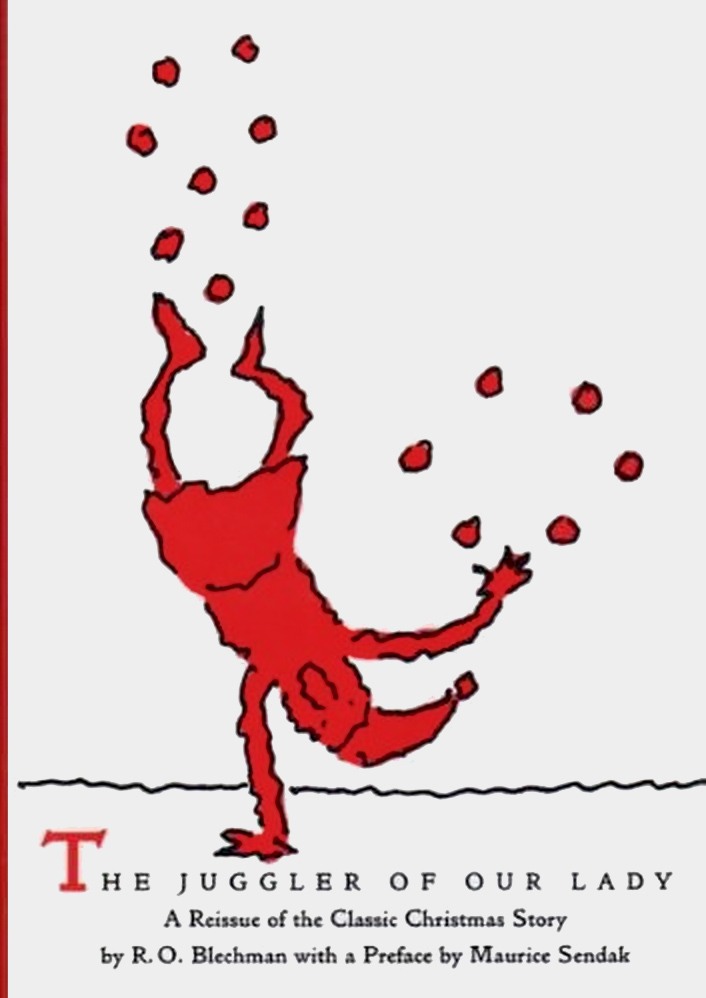

Published and illustrated in 1953, The Juggler of Our Lady, by R. O. Blechman, recounts the medieval legend of a hopeless juggler named Cantalbert who joins a monastery after failing to find an audience for his craft. Not sharing in the aptitudes of the other monks, Cantalbert is assigned to odd jobs around the monastery that no one else wants to do. When it comes time to offer a gift to the Virgin Mary at Christmas, he despairs over having nothing prestigious to offer her like his brothers. Ultimately, he decides to give Mary the performance of a lifetime and juggles for her throughout the night. Come that morning, Cantalbert’s gift is Mary’s favourite.

The story does not end with Cantalbert leaving the monastery to return to a career in juggling. His joyous activity does not translate into his livelihood nor does it become a side gig. Instead, juggling remains the silly, beautiful, and gratuitous activity that it had always been for Cantalbert. The Juggler of Our Lady reminds us that the passions of our recreation, like the divine gift of our lives, are valuable without considerations of their usefulness. In a culture that monetizes everything, dare to do something priceless.

Get the latest issue in print or subscribe for the next three.