As the early form critics rediscovered, the Gospels themselves are the fruit of preaching. According to a justifiable translation of Eusebius’s quotation of Papias (c. 60–130), bishop of Hierapolis, Mark composed his Gospel from Peter’s “anecdotes” or little stories about Jesus for the church’s spiritual formation (Hist. eccl. 3.39.15). All four Gospels present Jesus as repeating and completing the biblical story of Israel’s redemption from Egypt and return from exile. Although his journey is finished, sitting resurrected at the right hand of God the Father (see Psalm 110:1, the most cited Old Testament verse in the New), the bride, his church, is being led by the Spirit through a long, trying wilderness. As travel guides, the Gospels are immediately and essentially applicable for Christians. (For this reason, the majority of those who attend church hear the Gospels read every Sunday.) Preaching Jesus in little stories inside the big story invites participation from readers (hearers). Anecdotes typically remember something of the past – there are good reasons to accept the Gospels as source material for historians – but they are sufficiently sparse, the barest of settings and words, to make room for the Spirit’s creative work on our imagination.

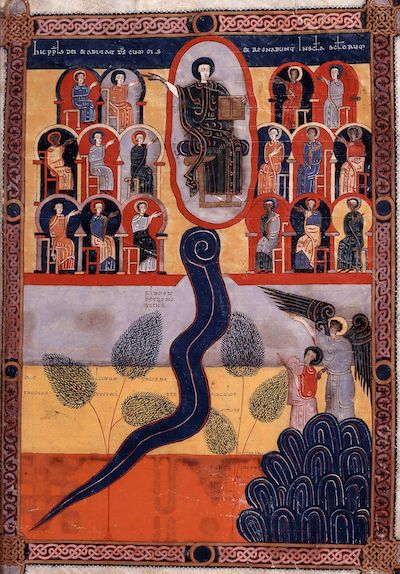

The Gospels express a pneumatic, participatory hermeneutic that we also find in the Dead Sea Scrolls, specifically the Pesharim; this way of reading Scripture can be simply expressed: “This is that.” This scene, this moment, this encounter is that biblical story. The presupposition is that God, the ultimate author of the Bible, continues to lead a people by the light of the Word through type scenes, allusions and echoes. The wilderness may look differently for every person and each community in our cultural dress and distracting idols, but it is the same journey between Paradise lost and regained. Jesus came from God, and we return to God in Christ.

And yet stories are driven by conflict and temptation. Indwelt by the Spirit, Jesus discerns that the Pharisees of his day inadvertently filled the role of Isaiah’s enemies, as the Spirit may reveal to us the Pharisees of today: “Rightly did Isaiah prophesy concerning you” (Mark 7:6). This ideology is not the gospel, not the way, but that same old idol with a new face.

To repeat and summarize: the same Spirit who led Jesus through a wilderness of temptation leads us (Luke 4:1; Gal 5:18). We all have been given a God awareness and the grace to respond (Jer 31:31). We all have been given the “anointing” and are therefore Christians or “little Christs” (1 John 2:20). There is the way of the flesh and the way of the Spirit, and these very different paths may be discerned by their fruit. The Spirit takes what Jesus said and reveals our distraction from and resistance to the narrow path that leads to life. The community that produced the Pesharim, the Yahad (“union”), most likely a branch of the Essenes, believed they had received the new covenant, also calling themselves “the Way,” although the Jerusalem church, our ancestors, counterclaimed the same epithet (Acts 9:2).

As Thomas Aquinas maintained, this way of reading (or entering) Scripture does not bypass the literal sense (sensus literalis), attuning signifiers (words) to their signifieds – what Confucius called “Rectification of Names” – it comes from a deeper signified, our union with Christ.

As preachers, we are most qualified to speak after sitting humbly in the role of the Pharisee, allowing God to convict our hearts and open our eyes: “Woe is me” (Isa 6:5). But then we need the courage of Jesus to confess what is not yet entirely clear to others in the community.

Recommended Reading

Richard Bauckham, ed., The Gospels for All Christians: Rethinking the Gospel Audiences. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1998. In this influential work, Bauckham and his friends make a strong case that scholars locked into the historical-critical paradigm have overly narrowed the intended audience (readership) of the Gospels to the specific communities of the evangelists. Rather, they were probably composed with some awareness of addressing the broader church.

Henri de Lubac, Medieval Exegesis. 3 Volumes. Translated by Mark Sebanc and E. M. Macierowski. Edinburgh, UK: T&T Clark, 1998, 2000, 2009. In the first volume, subtitled The Four Senses of Scripture, de Lubac re-introduces the Quadriga to the modern world. The cardinal was part of a movement in Roman Catholicism to retrieve the medieval worldview and exegesis of the church before the reductionism of the Enlightenment and the flatness of subsequent hermeneutical approaches to Scripture. Other significant voices of the ressourcement movement are Hans Urs von Balthasar and Jean Daniélou.

Martin Dibelius, From Tradition to Gospel. Translated by Bertram Lee Woolf. New York: Charles Scribners’s Sons, 1934. Dibelius, an early form critic, drew attention to the homiletical function of pericopes in the Gospels, claiming: “At the beginning of all Christian activity there stands the sermon” (37). Despite the overstatement, there is a grain of truth in this.

Geza Vermes, The Complete Dead Sea Scrolls in English. New York: Penguin Books, 1998. There are newer translations of the Dead Sea Scrolls, but the translator deserves mention for popularizing the expression “rewritten Bible.” A good place to start for understanding this genre is a slow reading of the Yahad’s commentary on Habakkuk (1QpHab) where the “Kittim” have become the occupying Romans but there are also enemies within Second Temple Judaism. For a more academic discussion, see Sidnie White Crawford, Rewriting Scripture in Second Temple Times (Studies in the Dead Sea Scrolls and Related Literature. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2008). She describes rewritten Scripture as “characterized by a close adherence to a recognizable and already authoritative base text … and a recognizable degree of scribal intervention into that base text for the purpose of exegesis” (13). For Vermes’s contribution to scholarship in this field, consult Rewritten Bible after Fifty Years: Texts, Terms, or Techniques? A Last Dialogue with Geza Vermes, edited by József Zsengellér (Supplements to the Journal for the Study of Judaism 166. Leiden: Brill, 2014).

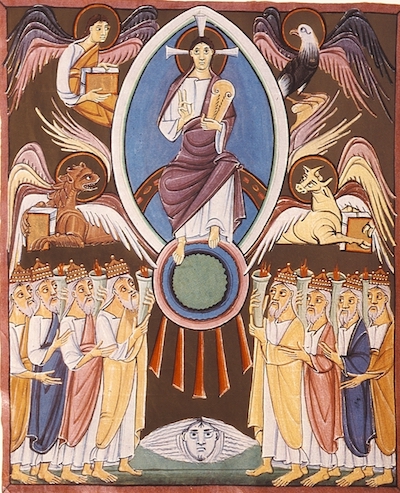

This Jewish hermeneutic evolved and flourished in the church as the Quadriga. Rabbinic interpreters recognized this and, in turn, borrowed the Quadriga from Christians, calling it Pardes (“Paradise”). This fourfold way of reading Scripture is displayed in Thomas Aquinas’s Catena Aurea (“golden chain”), a collection of glosses on the Gospels from Eastern and Western fathers. Aquinas insisted that the deeper senses of Scripture ought not to contradict the literal sense (sensus literalis). Another important work is Bonaventure’s The Tree of Life, which formed Franciscans in the way of the Gospels after their founder. His biography of Francis embodies the this-is-that hermeneutic. Ludolph of Saxony, a Carthusian monk, wrote The Life of Jesus Christ, which invited readers to enter imaginatively into the Gospel scenes. Milton T. Walsh is currently translating the volumes into English (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press). The work inspired Ignatius of Loyola’s Spiritual Exercises that formed Jesuit missionaries and was considered mandatory reading by Teresa of Ávila. The Quadriga enters English literature in the commentaries of Richard Rolle. John DelHousaye’s The Fourfold Gospel: A Formational Commentary on Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John (Eugene, OR: Pickwick, 2020, 2021) may be the first commentary to employ the Quadriga (Pardes) in over 500 years.