Dr Luis Cruz-Villalobos (PhD, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam) is a Chilean writer, editor and clinical psychologist. He is an Associate Fellow of the KLC. (See linktr.ee/luiscruzvillalobos.)

Poetry (1) was born in me to fulfil a function very different from that of rational thought, whether it is theological, philosophical or psychological thought. It was born as an urgent need to say something, to whisper a song … to sing so softly so as not to draw attention; rather, so that only the one who should listen would actually manage to hear the words. I remember that in my adolescence, after having already written a few notebooks of poems, I defined what poetry meant to me like this: “Poetry is like undressing behind the screen of the metaphor.” A poem allowed me to remain naked and yet hidden at the same time, free and anonymous, wide open, yet not completely exposed. With rational thought one cannot do this. It is like what Heidegger once said when he heard someone playing one of Schubert’s works on the piano: “You can’t do this with philosophy.” This is precisely why the philosopher from the Black Forest valued poetry and poets as much as he did.

For me, poetry and reflection or rational thought are distinct paths; complementary, but distinct. Many years ago, I wrote an article about hermeneutics and constructivism in which I discussed this. I commented that, from my perspective, there exists a mode of integration of personal identity that goes beyond the narrative identity as presented by Ricoeur. There is also a mode that we could call poetic identity, which is much closer to the pre-reflexive experiential processes that are not linear, causal, diachronic but rather circular, synergetic, synchronic. This poetic identity is much closer to the world of mythology, of archetypes, of spirituality that cannot be trapped by mathematical reasoning. For me, poetry is linked to this deep dimension that is particularly human, that connects us with the reality that is more primitive and necessary, that is to say, with fundamental confidence and joy. In other words, with love.

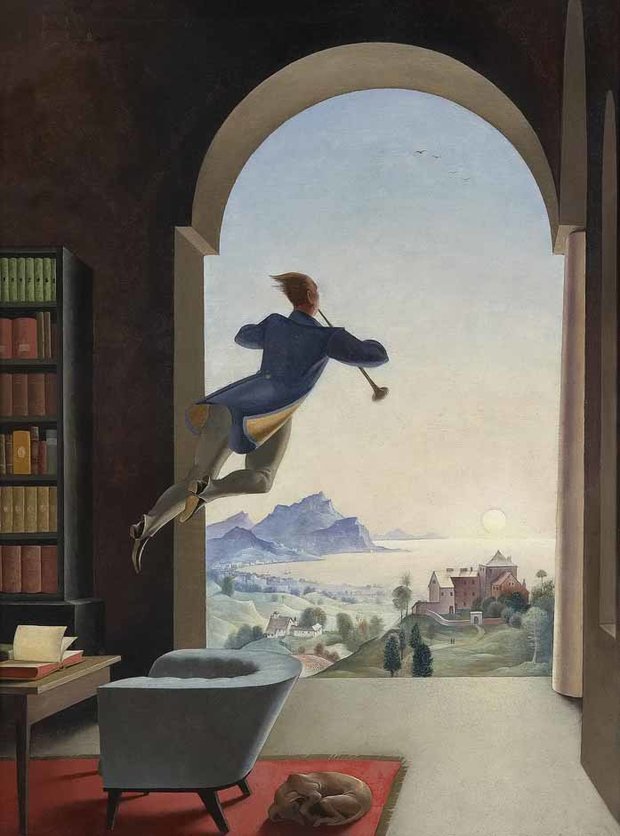

As a result, poetry has always risen in me like a spontaneous experience of connection with reality, or with the depth of reality, with the invisible foundation of reality. And with “invisible” I mean to say, just as a wise Sufi mystic once said: In the middle of the ocean a small fish asked a large fish where the ocean was because it wanted to see it, to which the large fish responded, “For that you’ll need to leave it behind.” Well, we simply cannot leave the ocean. We cannot get out of Being, out of Mystery, but poetry is a kind of juggling, a mysterious act that allows us the ex-tasis, the joy of getting out of oneself, or the Being of our being, to look from afar and to see. See the ocean. See the Invisible and celebrate it. We could also define the Invisible as the Beautiful, the Good, the True, the One.

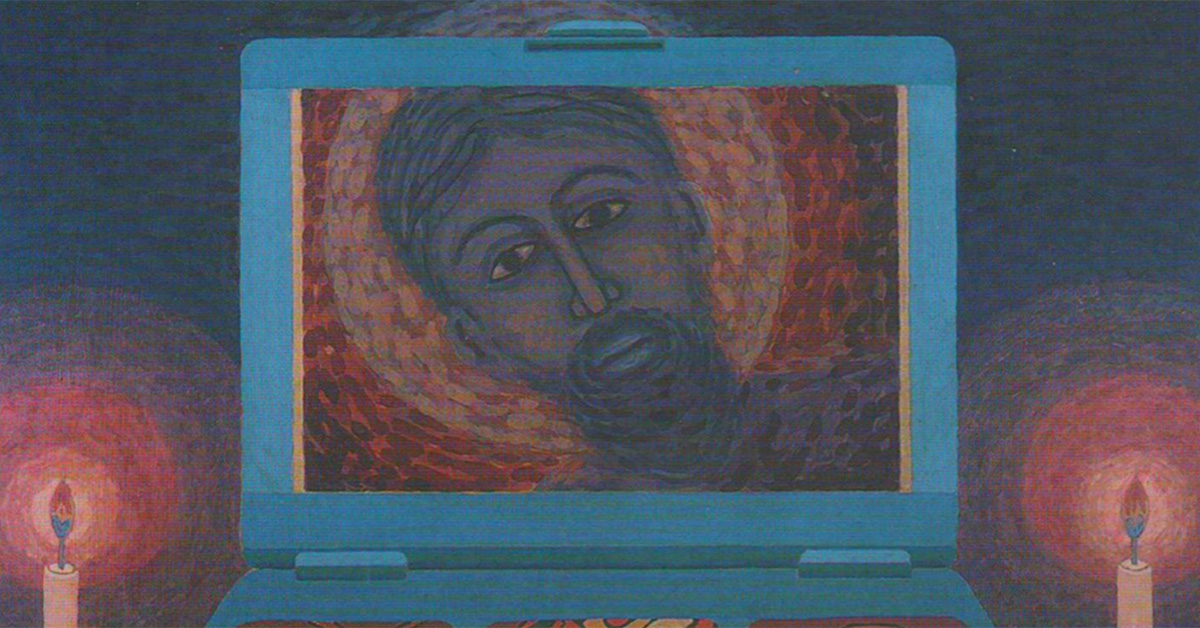

For me, poetry is the language of the heart from the heart. It is from this depth that I can see the Reality of the reality. Yet, poetry also connects us with the superficial reality, with pain, with loss, with what is ugly, but only so that we can be freed from its chains by naming these realities. We cannot do this through philosophy, nor psychology. Not even rational theology is able to do this, no matter what colour or particular hue it might be. Poetry is tied to mysticism. Yet, even poetry speaks of daily life, of the dark side of life, of what breaks our hearts, because if we follow the shadows, we will ultimately be led to the body that originated it and to the light that shines behind it.