Marit Greenwood is an artist who is drawn to contemplative spirituality.

I tend to be someone who is aware of my surroundings and I greatly enjoy nature, quiet and a contemplative setting. This makes sojourning in Origins Retreat Centre a “good fit” for me.

The buildings are understated: spaciousness dominates.

In the chapel, only a thin sheet of glass separates one from the extensive nature beyond and actually serves to provide a certain level of continuity with the general spaciousness. Nature enters the chapel – the odd bat, wasp and relentless call of the red-chested cuckoo that can last the whole duration of the silent meditation. And my exhalations join the air circulating the immediate and remote environment.

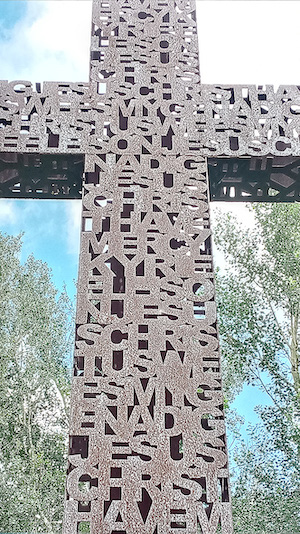

In the poplar grove, besides all the green life thereof, the intermingling of nature and human construction continues. Rust is claiming the exterior of the massive Cross-of-Words into a more restful ochre than its original metal glimmer; the face of the angel visiting Mary (one of the sculptures comprising the twelve stations of the life of Jesus incarnate) hosts a hibernating ladybird; the doves of another sculpture ascend and descend like a shower of leaves, trees playing host to their form.

And the image of God with extended hands invites me in.

Us in.

In.

“In Him we live and move and have our being,” we learn from the writings of Acts. And on the back of this particular sculpture, I find some spontaneous marks on the surface forming an imprint of a figure – myself by projection.

In Him indeed.

Have I capacity left to further marvel, I can leave the grove and walk up to the apex of the koppie (small hill) behind the grove. This takes me over weathered, elephant-skin dolomite, fine ancient sedimentary rock and quartzite stained a deep sienna. Up, further into the conservatory lands of the Cradle of Mankind, of which Origins is part. Up, past aloes, white-throated swallows and bobbejaanstert (black-stick lily) plants no longer in bloom.

From the top of the koppie I can regain perspective, the understated buildings now reduced in scale, even the Cross not visible behind the poplars and the chapel, as ritual place to meet quietly with God, now replaced by a vast, endless natural arena for worship. The focus of that worship now somehow with less definition, less boundary, not even just a thin pane of glass. More pervasive now, resembling more that part of the Trinity we name Spirit. Breath. Air. More immediate too as a sudden breeze refreshes me in the heat and as I breathe in the next breath of air, or is it the next breath of Spirit?

In Him we live. … Where and how does metaphor roll over into reality?

Only after having written this last paragraph which refers to a blurring of boundaries and a taking into myself that which is external, do I realise that I had stepped experientially into what Peter Leithart in his compelling book of theological speculations, Traces of the Trinity, describes. “My connection with the world is a Celtic knot. Inside and outside form a Möbius strip that folds back on itself” (4).

Not only of the world, but also with its Source, the Triune God.

Indeed, my entire stay at Origins attested to this indwelling of so many things by each other in the created order, to a “perichoretic pattern” (144) fundamentally reflecting the circumstance that all such patterns are essentially “traces of the Trinity … find[ing] their source and root in the fellowship of Father, Son and Spirit, each of whom indwells each other in a far more profound and exhaustive fashion than we find in creation” (136).

In. And my life depends on it.

Get the latest issue in print or subscribe for the next three.