Aston lives in Nottingham with his wife and is part of a local church who meet there.

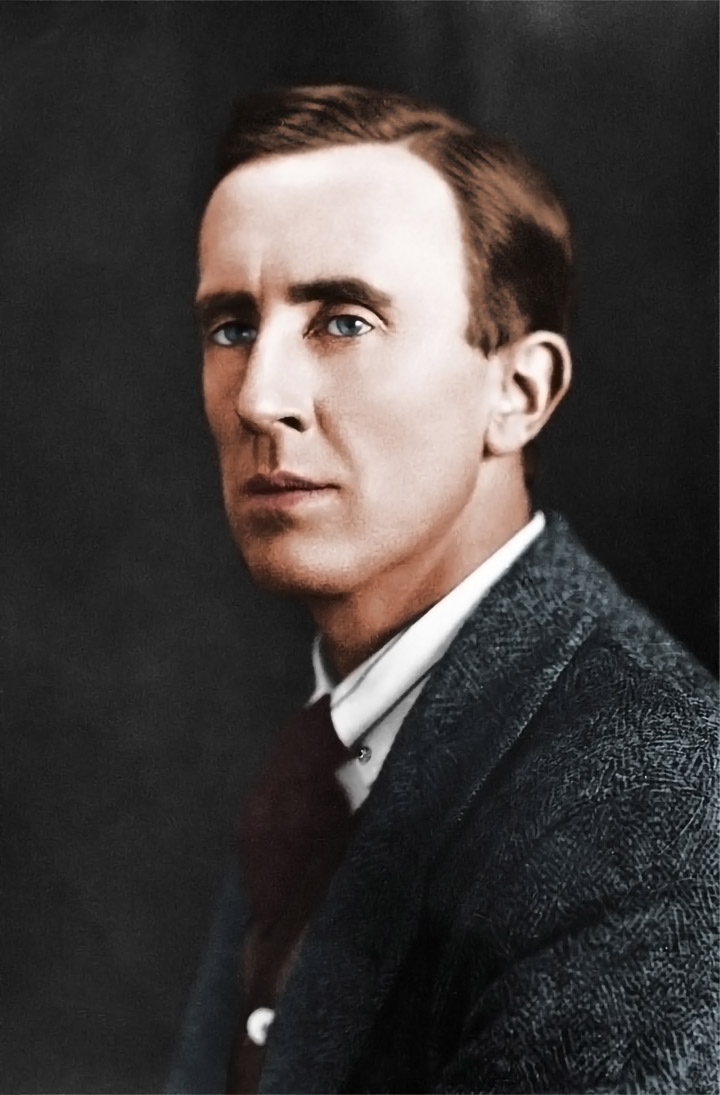

It is easy to write off lovers of J. R. R. Tolkien’s work as those who have a kind of trivial interest in merely good stories – those perhaps with a bookish or imaginative bent. But this is often mistakenly simplistic. Tolkien’s literary work can be appreciated as much more than just good stories, they can also offer relevance to modern-day issues relating to human making and living. For example, what does a set of books published in the 1930s–1950s set in a fantasy world with pre-technological, medieval sensibilities have to tell us about future technological aspirations? Actually, more than might be at first thought.

Aragorn, the long-awaited king in the Lord of The Rings trilogy comes from a line of men with a history filled with both immense glory and tragic woe. The Númenoreans received the island of Númenor from the Powers, angelic beings in the west of Middle-earth who are its guardians. This island which the Númenoreans called their home was a gift for faithful service in battle against the forces of darkness. The people of Númenor grew in might, power and splendour. Nature on the island blossomed and the blessing of life was evident in all its fullness. Although they lived for hundreds of years, they were still mortal like the rest of men. Over time, however, the Númenoreans became dissatisfied with the boundaries imposed on them by the Powers. They desired to roam the seas and conquer other lands. And still another gnawing desire grew upon them – the desire for immortality.

The Númenoreans began to hunger for the undying city that they saw from afar, and the desire of everlasting life, to escape from death and the ending of delight came upon them; and as ever as their power and glory grew greater their unquiet increased.” (The Silmarillion [Harper Collins, 1999], 315)

Akallabêth

And they said among themselves: “Why do the Lords of the West sit there in peace unending, while we must die and go we know not whither, leaving our home and all that we have made?”

“Why should we not envy the [Powers], or even the least of the Deathless? For of us is required a blind trust, and a hope without assurance, knowing not what lies before us in a little while. And yet we also love the earth and would not lose it.” (315)

Akallabêth

One subject that deserves attention is the modern ideology of Transhumanism. Transhumanism is a broad set of aims, hopes, aspirations and philosophical claims which centre around augmenting the human experience of life, transcending our limitations and radically expanding our capabilities – using science and technology. This might include technologies from artificial intelligence, to highly sophisticated powerful algorithms, to expanding the power of the brain with technological upgrades. But more shocking is the interest in overcoming the problem of death. A number of solutions are proposed for this. Extending consciousness by uploading it to some kind of cloud technology, freezing the human head or body to “resurrect” when the technology is perceived to be ready or prolonging the life of the body indefinitely.

Transhumanism will lead humanity forward to understand what seems like a simple truth: that the spectre of ageing and death are unwanted, and we should strive to control and eliminate them.

Zoltan Istvan

In 2030 we will be ageless and everyone will have an excellent chance to live forever. 2030 is a dream and a goal.

Fereidoun M. Esfandiary

It is tempting at first glance to see Transhumanism as a somewhat juvenile, wishful fancy or hobby which is hardly worth taking seriously. However, like the trivialising of an interest in Tolkien, I believe this would be a serious mistake. Transhumanist claims are not merely a fanciful interest like comic books or science fiction. Several proponents of Transhumanism are influential, wealthy, powerful – or a combination of these. Historian Yuval Noah Harari receives accolades from Barack Obama, Bill Gates and Mark Zuckerberg and is a key member of the highly influential World Economic Forum. Elon Musk is one of the wealthiest men alive and committed to innovation in various fields. Professor Brian Cox is a popular physicist with programmes broadcast by the BBC. Harari, Musk and Cox are all confident that humans will achieve life unending.

It’s also easy to see why these ideas, fringe though they may be now, are in danger of gaining wider appeal. The Transhumanist vision of overcoming death is in many ways a utopian narrative. It seems as though a form of widespread health and security is being offered to humanity as a whole for the common good. Who would control this new power and which elites would distribute its goods is a disturbing question that we will gloss over for the time being. It is worth noting that at times these visions of human grandeur are not merely filled with pseudo-Christian overtones – they are expressed in explicitly religious terms.

Having raised humanity above the beastly level of survival struggles, we will now aim to upgrade humans into gods and turn Homo sapiens into Homo deus.

Yuval Noah Harari

Like the people of Númenor, Transhumanists who seek to overcome death are seeking to wrest the power of life and death from God – even if they claim not to believe in him. Science and technology have been the instrument of much material good in the world by alleviating various aspects of poverty, sickness and pain in life. But there is a forbidden fruit which Transhumanists want to reach out and grasp, just like the race of Númenor – to live forever on man’s own terms and be like gods. Contentment with one’s lot in life and the relative prosperity we have access to is not what is being advocated. In many ways, here is an atheism that is not content to embrace the claimed “nothingness” that lies on the other side of death. On the other hand, it betrays a kind of Gnosticism which seeks to advance humanity to become divine. On the island of Númenor such pursuits ended up in very dark places. The temple to the creator of Middle-earth, Ilúvatar, was torn down and human sacrifice began to be practised. And the discontentment grew.

But for all this Death did not depart from the land, rather it came sooner and more often, and in many dreadful guises. For whereas aforetime men had grown slowly old, and had laid them down in the end to sleep, when they were weary at last of the world, now madness and sickness assailed them; and yet they were afraid to die … and they cursed themselves in their agony.” (328)

Unsurprisingly, the people of Númenor were mistaken. Tolkien highlights the reality that living forever would not be a utopia even if it were achievable. The elves of Middle-earth had perpetual life, yet they had to endure the grief and frustration of a world marred by evil over millennia – unless they could bear it no more and wasted away in grief.

The hubris of the king of Númenor eventually reached its peak. Setting sail to make war on the Powers and wrest the gift of eternal life from them, the people of Númenor met their end. The Powers stood aside and petitioned Ilúvatar to act. Ilúvatar’s subsequent destruction of the Númenoreans gives a nod to the legend of Atlantis. Apart from that remnant that chose not to follow such evil, the island and its people are swept away in total judgement.

Tolkien’s Middle-earth saga portrays the beauty of the earth and the beautification of bodily life. It also portrays the grief of life marred by evil. The saga’s history of the Númenoreans show the perils of dissatisfaction with the shortness of life – even though this brevity itself is a gift. Transhumanist hopes of humanity transcending death through technology are eerily similar to such dissatisfactions. Tolkien’s tale seems prophetic of current technological aspirations – probably because he is drawing on the Christian faith which is piercingly insightful of human nature. The same pride evident at Babel returns again and again.

The reality is that death is both a judgement and a gift. Although God’s judgement of death came because of Adam’s sin, the reality of death and the shortening of life decreed in Genesis chapter 6 also comes with mercy to God’s people. This truth is highlighted by the world before the flood. For a person to bear with the toil of this life century after century is no easy task – especially in a time of particular evil surrounded by evil people with enduring power. Death is also crucially a judgement: decreed by God for sin. One of the key issues with Transhumanist hopes of unending life, is that it aims to overturn this judgement and outwit the judge who gave it. But God cannot be cheated and judgement is only taken away in and by Christ:

For the trumpet will sound, and the dead will be raised imperishable, and we shall be changed. For this perishable body must put on the imperishable, and this mortal body must put on immortality. When the perishable puts on the imperishable, and the mortal puts on immortality, then shall come to pass the saying that is written:

“Death is swallowed up in victory.”

“O death, where is your victory?

O death, where is your sting?”The sting of death is sin, and the power of sin is the law. But thanks be to God, who gives us the victory through our Lord Jesus Christ. (1 Cor 15:53–57)

This has been accomplished in Christ alone for all who will trust in him.