With a life-long interest and endless curiosity about humanity, Megan Greenwood (www.mgcoaching.org) enjoys empowering people and journeying with them as they discover how to more deeply live from their core. All photographs by the author.

I didn’t usually go for walks at 4am. However, on this particular morning I found myself noticing the shadows of trees being cast by the streetlights onto the grey, broad, cement sidewalk as I made my way down it in the cool, pre-dawn air. The public square that, every night, blasted a cacophony of congested, competing songs from different groups of dancing grannies engaged in their nightly exercising ritual was silent as I passed by. The main road that usually huffed and puffed with buses, cars, bicycles, three-wheelers, honking horns and human footsteps was quiet, except for an occasional purring taxi. In a city housing over three million beating hearts, I found a surprisingly spacious solitude as I made my way to meet a friend.

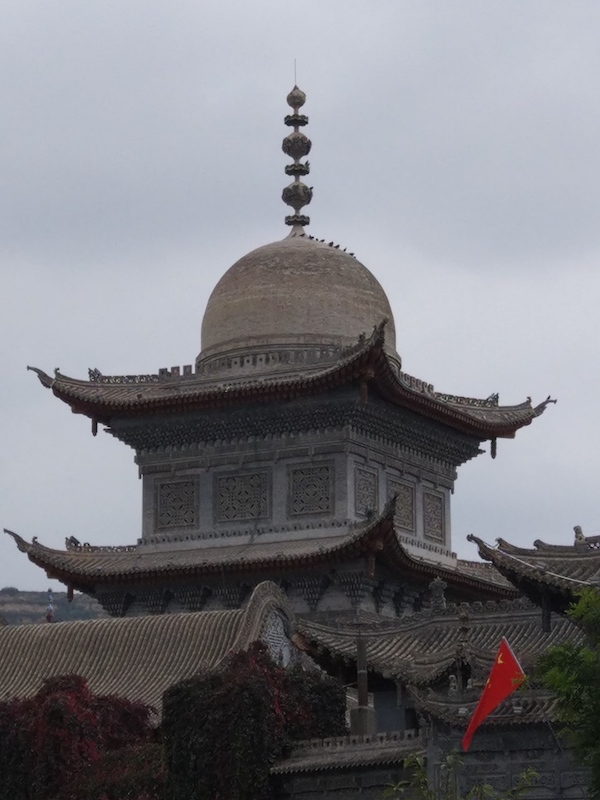

It wasn’t usual for us to rendezvous in dark, pre-dawn hours! But this wasn’t a usual morning: it was Ramadan. My friend was DongXiang 东乡. He belonged to a predominantly Muslim Mongolic ethnic minority group found in northwest China. Each year he entered into the rhythm and ritual of the month-long fast that wove together the fabric of his religious and cultural community. This year, I and another colleague from the university where I taught, decided to accompany him for a day of fasting. It meant eating together before sunrise, which was when the day’s fast would begin.

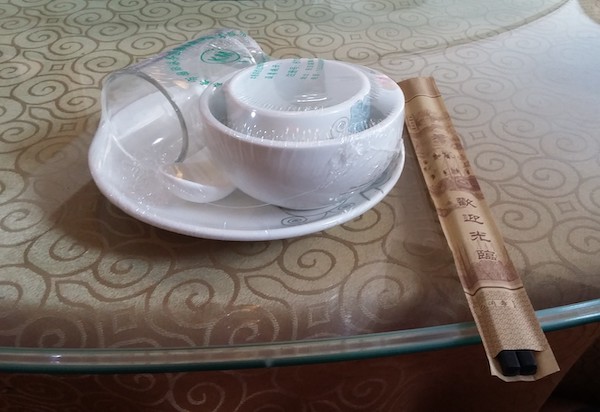

I turned down the street towards the restaurant where we were meeting and caught sight of steam rising from a huge cauldron behind the counter at the back end of it. This was a noodle restaurant, serving freshly-boiled, hand-stretched noodles of an array of thicknesses in a bowl of flavourful broth, sprinkled with cilantro, Chinese radishes, scallions, deep red chilli oil and shavings of beef. This city, my Chinese “hometown,” was renowned for this dish. True locals ate a bowl of beef noodles every morning for breakfast. They claimed that eating it any later in the day meant the broth was no longer fresh. As a waiguoren 魤国嬣 (foreigner), I grew up thinking pasta – my nearest childhood equivalent to noodles – was eaten for “lunch” or “supper” more readily that pre-sunrise meals. But this morning, aided by chopsticks, I slurped my way through its weighty warmth.

I’d be lying if I said I could recall the conversation we had, as this meal took place about five years ago. What’s more striking to me now is reflecting on how this young gentleman’s path crossed and shaped mine. He was one of hundreds of university students I taught, and one of many I had befriended as I witnessed their university experience. He grew up in a predominantly Muslim autonomous region, so entering university meant being thrust into a space that more acutely highlighted his “differences” and minority status. This required him to frequently navigate cross-cultural interactions with, and stereotypes and assumptions held by, Han ethnic majority classmates. Although usually well-meaning, most of them had had limited exposure to cultural differences and had been fed a somewhat romanticised, essentialised view of China’s fifty-six recognised ethnic minorities. Perhaps that alone created common ground between us, as my existence in China was an ongoing cross-cultural dance and misidentification was common. (“No, not all foreigners are American. No, not all South Africans are black. Yes, my mother tongue is English – and yes – I come from Africa.”)

In addition, both of us were pursuing our respective faiths in a context where the predominant flavour of the day was – and is – atheism. Through his actions, not words, he began to open my eyes to what this meant for him. When extra-curricular activities were hosted at certain spaces by me or other foreign teachers, he was absent. This puzzled me – especially in an indirect, highly relational context. What did it mean? Eventually it dawned on me that we were choosing non-halaal spaces. No wonder he was absent. Enthused by my insight, I tried to be more sensitive. While other students took extra cookies we’d baked together back to their dormitories as snacks, he politely refused them; they were not halaal. This, despite my explanation that I had specifically purchased halaal butter, in the hope that they would pass as acceptable. I grew to know how food could exclude or include. That awareness emerged gradually, along with a clearer sense of what being a people “set apart” could look like. I watched the choices he made, including his annual devotion to partake in Ramadan, which he described as helping him to recentre towards creator God. I saw it too as a pursuit of holiness.

By the time his final undergraduate year came, I more readily recognised the 清真 (halaal) sign on restaurant windows that designated them as welcoming spaces for him. They’d become our meeting grounds. It was also in his final year of studies that the idea to join him in his fasting emerged, leading to this moment of slurping noodle broth together before sunrise. Soon enough, sunlight replaced streetlights and tree shadows. Full stomachs replaced full bowls. We parted ways, heading into the activities that lay before us that day. I was extra careful to not let food or water touch my lips as the day passed by.

We bookended the day with another shared meal, reconvening after sunset at a gate of the university. My friend led us down a skinny side-street to a spot I would not have found alone. We squished into a tiny corner upstairs and were brought a large platter to be shared. Literally translated as “Big Plate Chicken,” it included belt noodles – their name derived from their generous thickness – slices of potatoes, veggies, a whole chicken cut into pieces, and a medley of Chinese spices all swimming in the characteristic red chilli oil which had many a time left its signature flick on my clothing.

Tummies full, we departed. I made my way back towards my apartment. The grannies were dancing vigorously. The night’s traffic was diminishing, but not yet at its 4am low level. I wove my way between clusters of students holding phones, snacks, or plastic packets with cups of boba tea in their hands that cast swinging shadows on the sidewalk.

I was mindful of the fact that my tomorrow would not follow the same rhythm as my friend’s. Once again, he’d encounter the fresh dawn air. And again. And again. And again. I would not. At least, not in that way. Nevertheless, I still carry with me the essence of his imago Dei, clasping chopsticks and sharing space at a table of common ground – one where there’s always room for one more.