Peter S. Smith is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Painter-Printmakers and former Head of Kingston College School of Art, Design and Media (1984-2010). He has a BA Fine Art (Painting) from Birmingham College of Art and Design (1969) and an MA in Printmaking from Wimbledon School of Art (1992).

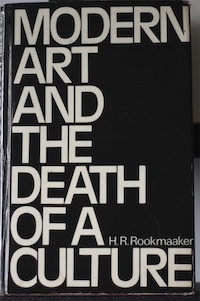

The first Impressionist exhibition in Paris in 1874 faced severe critics, but much has happened in the intervening years to modify our view of their work. Standing in front of a Monet painting today, we can understand why those first critics were shocked, but we cannot easily share their emotion. Dr Hans Rookmaaker’s book Modern Art and the Death of a Culture was first published in 1970. If we are to make sense of it today, we need to contextualise it. It contains no reference to now familiar works made after 1969 and an artist’s later works may modify our earlier opinions about them. The book was a 1970s’ call to action, rather than an academic treatise.

If you use the term “modern art” to refer to all contemporary 20th-century art and read Modern Art and the Death of a Culture in that light, you will find fault. Rookmaaker regarded modern art as one stream within contemporary 20th-century art. It was a kind of powerful subculture, supported by a group of artists, museum curators and art critics, who successfully presented modern art as THE art of the 20th century. He was not alone in suggesting this, but after his death in 1977 more writers began to agree that Modernism was such a subculture. By the 1980s this had become the prevailing opinion. In a 2018 Sunday Times review of America’s Cool Modernism, art critic Waldemar Januszczak wondered why some 20th-century artists represented in the exhibition had been previously overlooked by that Modernist agenda.

How did Rookmaaker distinguish modern art from contemporary 20th-century art? In modern art he identified certain common concerns, while not suggesting all are present in any particular work. Often there was a nihilistic attitude, which regarded humanity as absurd and alienated from the world. There may be a view of creativity and spirituality which is fed by neo-Platonic or neo-Gnostic roots. In Rookmaaker’s view, this devalues the created world, turning it into an alien place which obscures and hides “real” reality. There may be an interest in Eastern philosophies, theosophical movements, or a kind of secular mysticism. The older notion of “artist as prophet” still existed, but was modified to include the idea of artists as visionary figures with special insight to interpret their times. There was a desire for a revolutionary break with the past and its conventions.

Contemporary 20th-century art had different intentions. Arising out of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, there was a growing rediscovery that a painting is lines, shapes, forms and colours on a flat surface. Rookmaaker’s term for this is the “iconic element.” These visual language elements, as they are used together pictorially, depict an artist’s understanding of the structure of reality. They always give us more than the eye can see. A portrait by Rembrandt and a child’s drawing of a face, can both be structurally clear in their use of a pictorial language and enable us to recognise a face. For Rookmaaker this meant that we can reject 19th-century naturalism as the only way to depict appearances and explore more expressive ways of working with these renewed stylistic means. This 20th-century work, while it may be innovative and challenging, does not search for such a deep break with the European tradition. It still explores more normal human experiences and views of reality.

Does this mean that we can simply classify our artists as either sheep or goats? Rookmaaker recognised that individuals are complex and beyond simplistic labelling. It is possible to discern a straightforward use of 20th-century contemporary pictorial language in one work, whilst another, by the same artist, may show a Modernist attitude. Rookmaaker had great faith in the painting as the primary source of meaning. He had a high regard for Picasso as an artist, admiring Picasso’s use of pictorial language in his painting Guernica. However, he objected when in other work, Picasso’s interest in Nietzsche made evident an absurd view of humanity or reality. Rookmaaker asked if it is clearer to find traces of Gnostic thought in the catalogue of a Rauschenberg exhibition, or to recognise those traces in the work itself. He was convinced that the work itself is both clearer and more explicit.

Is Modernism just a style? Again there are no easy answers. For Rookmaaker the modern movement was not a style but an attitude, a certain spiritual insight or a feeling for the predicament of humanity. This can be expressed in a variety of styles. He listed naturalism, a certain kind of mannerism, or expressive iconic types of visual communication. These different pictorial languages are also used in 20th-century art without Modernism’s intentions or undercurrents.

Significantly, Rookmaaker found modern art full of religious and spiritual content. In 1968 he introduced me to art historian Sixten Ringbom’s work on the mystical and theosophical themes in modern art. This spiritual element has been hidden in plain sight, because many of the institutional guardians of Modernism chose to overlook it. Waldemar Januszczak argued, in a 2021 article, that the art historians and institutions of Modernism repeatedly ignored any idea that in Modernism there can be found religious or hermetic intentions. There was a fear that it would sully the waters. Artists, like Kandinsky, who had been accepted into the Modernist canon, never hid their interest in religion and theosophy. According to Waldemar Januszczak:

It wasn’t the artists who were hiding their spiritual drives. It was the organisations that had taken custody of their reputations.(1)

Rookmaaker never doubted that these “spiritual drives” are present in modern art. For him the real question was, what kind of spirituality or religion is being advocated. He recognised that many modern artists struggled with the loss of a spiritual dimension, which grew out of a disenchantment with aspects of Enlightenment thinking. He did not doubt their ability to articulate these concerns. He empathised with them, while questioning their solutions.

Rookmaaker believed that the 20th-century renewal of pictorial language opened up new and exciting ways of working. He was equally aware that pictorial languages are not neutral but devised to disclose particular attitudes or points of view. However they are malleable, so he found no contradiction in praising Feininger’s and Delaunay’s use of Cubism’s pictorial language as positive rather than Modernist. He also speaks of beautiful work by Matisse.

Rookmaaker’s particular view of Modernism; his interest in the plurality of different streams in 20th-century art and his suggestion that industrial design, advertising art and contemporary typography should be included in the study of 20th-century art, anticipated aspects of postmodernism. However, he would have rejected postmodernism’s lack of belief in the possibility of a shared understanding of external reality. Despite our varied worldviews, central to Rookmaaker’s thinking was a conviction that, in our humanity, we do share a created reality to which we all have access. This reality, which includes the visual arts, is ordered by God’s structures and norms which, in turn, open up possibilities for us to discover. To reject them leads to abnormality. For this reason Rookmaaker was wary of the term “Christian Art.” Even with good intentions, Christians may make poor art, whereas, when acting out of their created humanity, artists with no Christian profession do produce beautiful and truthful work. It may be better to speak about art which does justice to reality. However, Rookmaaker was never prescriptive about the ways in which artists who are Christians should work. Rather, they are free to explore and disclose Christian attitudes and ways of thinking in a contemporary way in a contemporary context.

Rookmaaker’s restricted use of the term “modern art” means that many works, previously thought of as Modernism, can be seen in a different light as innovative and positive 20th-century contemporary works of art. Today, 21st-century art institutions promote contemporary art practice as vigorously as they did Modernism. One key characteristic of contemporary art practice is a focus on societal “issues.” Again, this is only one stream in contemporary art, but it still shares Modernism’s conviction that the artist is a special person with an elevated “prophetic” role. Rookmaaker’s challenge to that idea of the artist’s role still stands. He reminded us that we do not need to be modern in order to be contemporary. Perhaps one of our questions now should be, “Do we have to engage in contemporary art practice in order to be contemporary?”