Sarah Beth Baca is a painter, illustrator and entrepreneur who lives and works in Houston with her husband and their three children. (See https://www.sarahbethart.com.) All paintings by the author.

Have you ever found yourself wondering why an artist’s work evolved – what made them explore or wholly shift the direction of their work? If you compare the early work of Lee Krasner or Henri Matisse with their later work, you’ll see an intriguing change in style, theme and colour. This visual representation of an inner transformation fascinates me as an artist. In a sense, art gives us a graphical documentation of the stages of a person’s life.

Like many artists who came before me, there have been seasons in my life when my art has undergone considerable renovations. As an artist who grew up in the Christian faith, this visible change was directly connected with my inner faith journey. But, before my craft could change, two things had to take place. First, I had to be willing to step into the uncomfortable, and second, I had to muster the courage to tell a story.

As a beginner art student in college, my ideas and concepts for what my art could say or mean were solely informed by my professors and limited life experiences. I didn’t know much, but I knew I loved to paint. Art gave me a voice to speak a new language of colour, shape and texture. Still, I painted out of assignment; I painted what I saw in magazines; I painted the ideas of other artists I admired. Eventually, I began to paint things I enjoyed but only what felt safe … sticking to trees, boxes, chairs, impressionist landscapes and plants.

A shift happened in my early art career, and concepts like redemption, forgiveness, transformation and renewal rose to the surface of my work. I felt a tugging in my spirit to start conversations and bring hope and courage to others through my art. Instead of simply building skills and creating visually appealing work, I wanted to impact the world around me through art.

As a young mother, I encountered another crossroads when several troubling passages of the Bible surfaced, and I was challenged to face them head-on. For the first time as a Christian, I took a deep dive into theology and women in Scripture. You see, throughout my life, I’d felt overlooked by God as a woman. I’d avoided addressing this feeling for decades, but I couldn’t run from it any longer. If my relationship with God was to go any deeper, I needed answers.

After several years of wrestling through the misconceptions I’d grown up with about the Bible and being a woman in the church, I grew deeply in my faith connection to God, coming to see myself and women in the Bible through a new lens. This immersion of learning and conversation was a formative time that produced a desire to tell the stories of these biblical women through my art. I didn’t know it yet, but my learning process was about to birth a new venture. For the first time in my artistic journey, I wanted to tell visual stories. But, unlike my previous creative endeavours, I didn’t feel equipped to take on the task before me.

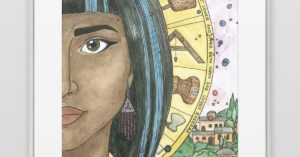

With no clear plan in sight, I swallowed my fear and stepped into the unknown. After spending time studying the story of the Samaritan woman at the well, also known as Saint Photina, I sketched out half of a face inspired by traditional Orthodox iconography. I added some colour and line work. Unsure, but excited to share what I was learning, I shared my reimagining of Saint Photina on social media along with her story. The response to my unique perspective was astounding. In my small network alone, I saw a hunger to reexamine familiar (and some less familiar) biblical stories of women.

The dialogue sparked through that one piece energized me, motivating me to continue and see where the road would lead. Next, I painted a second portrait, Abigail, sharing her image and story. As time went on, I developed a rhythm. Armed with a list of women I wanted to portray, I’d pick one and then start learning as much as I could about her by reading multiple translations and commentaries. I’d then dream up a colour palette, following my instincts with watercolour paint, using whatever skin tones, hair colours and details came to mind. Then I would identify symbols that related to the woman’s story and, finally, add ink for detail. Each woman was depicted with half a face and a halo in the background.

Before I knew it, painting these portraits of women became a meditation for me to connect with the lives of women who’d lived generations before me. I was using my artistic skills to tell stories in a new way, and in a way, I was finding myself in the process. Inspired by elements of their lives, I was empowered to engage in my faith in the most profound way I’d ever known. I wasn’t just painting; I was growing deeper in my calling and purpose. And, somewhere along the way, as the ink dried on the pages, the weight of expectations and stereotypes I’d carried for decades sloughed off, and I was finally free … to be myself. But I wasn’t the only one who changed in the process. As I shared those women’s stories, others also connected with the work in ways that inspired and encouraged them to live out their own callings.

So, back to my original question – what sparks an artist’s work to transform throughout a lifetime? My struggle with faith and discovering my identity as a woman of faith set me in a new creative direction of illustrating stories I wanted to share with the world. Lee Krasner’s work visibly changed from cubism to a looser abstraction as she worked through her grief after her husband, Jackson Pollock, died. Henri Matisse altered his style and technique because of sickness and limited mobility. Painting had become difficult, so he redirected his creative flow to cutting out coloured paper in order to “paint with scissors.”

Perhaps it’s not the outer shifting of an artist’s work that holds the most weight but the inner transformation that remains unseen. That burning off of the old self and the welcoming of the new is a risk we artists take. Hoping to bring what’s underneath the surface into the light, old mindsets and methods are cast off as we step tremulously into the unknown. But as we take that chance of exposure, of being seen for who we are, we give our audience the courage to do the same.

When I share new and untried artwork, there’s almost always discomfort. Inevitably, I feel exposed and laid bare before the world. But then, miraculously, someone reaches out with a journey that echoes my own. And, then, somehow, as if it had a life of its own, the art that came out of so many things in my life being reborn offers that same gentle nudge to a perfect stranger, pushing them out of old habits and mindsets and into a new story all their own.