Bridget Nichols teaches liturgy and Anglicanism at the Church of Ireland Theological Institute in Dublin. With Gordon Jeanes, she is the editor of Lively Oracles of God: Perspectives on the Bible and Liturgy (Liturgical Press, 2022).

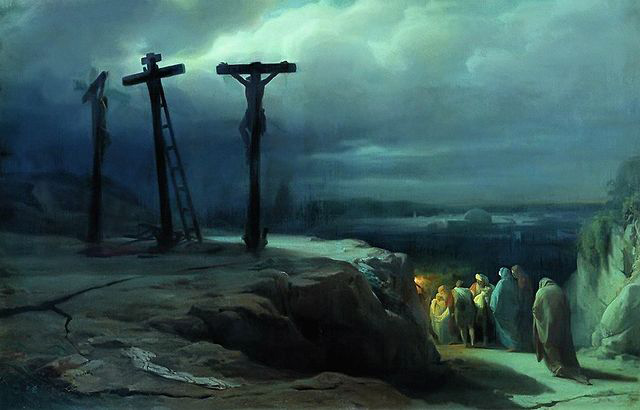

That lament has become a dominant theme in the composing of texts for worship should not surprise anyone who has followed contemporary events over recent years. The surprise, perhaps, has been that this is not innovation, but rediscovery. Lament belongs to the most ancient fabric of prayer. It confronts us in the writings of psalmists and prophets, and in their recapitulation in Jesus’ own lament over Jerusalem and last words from the cross.

Yet there is a temptation to be cynical – the same temptation offered by an overused commodity. Has the apparently irresistible urge to attach laments to public acts of worship, especially those crafted to respond to current or historic events, become merely a device signalling the right sort of consciousness on the part of organisers and participants? Here, we might legitimately distinguish between good lament and bad lament. Good lament is surely the truthful naming of things cruel and shameful and horrifying by communities who are still clinging, however precariously, to hope in the faithfulness of a God who listens and eventually acts. Bad lament founders in its own catalogue of regret and struggles to achieve any turn towards hope.

If lament is again being recognised as a vital part of what makes the discourse of prayer “authentic” (a word to be used thoughtfully and carefully, and with Charles Taylor’s Ethics of Authenticity on a nearby bookshelf), then we owe it to ourselves to do it well. By that I mean not so much a polished and eloquent performance, as an utterance that does not require rigorous analysis to defend its truthful credentials. John Witvliet is one of the surest guides and some of his principles set the standard to which writers could profitably aspire. Lament should be personal and direct. It should not be clogged with qualifications or conditional expressions. It should use strong words – “those less fortunate than ourselves” make less of a claim than the unedited naming of our neglect of the poor and desperate. Lament should also disrupt the regular prayer patterns of the worshipping community. A mass shooting, or the abduction of schoolchildren, or the murder of a local resident properly cuts across the prescribed readings for the day and the intercessions composed a week ahead of the service.

Lament is above all an inhabited process. If hope comes as its final outworking or poetic turn, such hope can never be taken for granted. For that reason, Witvliet says we should lament slowly, perhaps praying through a psalm over a whole hour. At the end, something has changed in us. Perhaps that is all that needs to happen – the testing of the integrity of our humanity (a point Wendell Berry makes in

“A Poem of Difficult Hope”).

That returns us to the question of whether lament can be introduced too often into the practice of worship. One obvious conclusion is that it has its own urgency. We know by attending to the world we live in, local and global, when lamentation is called for. Communities may be less clear as to when their own conduct calls for corporate lament. We go on needing Ash Wednesday and the penitential psalms.

For Further Reading

Taylor, Charles. The Ethics of Authenticity. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1991.

Witvliet, John D. “What About Liturgical Lament?” http://eredienstcreatief.nl/witvliet3.pdf

– – – . “A Time to Weep: Liturgical Lament in Times of Crisis.” https://www.reformedworship.org/article/june-1997/time-weep-liturgical-lament-times-crisis

Get the latest issue in print or subscribe for the next three.