Jorella Andrews is Professor of Visual Cultures at Goldsmiths, University of London. All artwork and photographs by Mary Abma (www.maryabma.com).

Jorella Andrews: As an artist focused on the natural environment you’ve said that you consider the whole world to be your studio. This orientation developed from a focus on your own back yard and has led to diverse projects in wild, remote and often also ecologically fragile regions. Could we start by talking about the studio in your yard?

Mary Abma: I first moved my studio outdoors in 2009, while working on an exhibition called “In My Own Back Yard.” I had heard about biodiversity loss and wondered how my own lack of attention might impact the environment around me. So, I turned to an artistic and scientific investigation of my suburban lot in Bright’s Grove, Ontario. When we first moved in, the yard was only lawn. We had one tree, a shagbark hickory, which is native to our area.

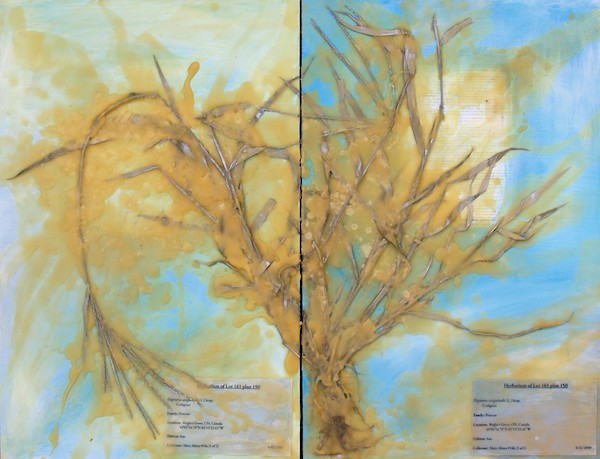

When I started the project, I knew nothing about botany. First, I had to find out what was growing in my yard, and to discover the stories, the histories, behind this growth. I left my lawn alone for a whole growing season so that every plant that was there could spring up of its own accord. I made an artistic herbarium of the eighty-two different species of plants I had collected, none of which I had planted. What I learned from making this piece was that most of my plants shouldn’t have been in my yard!

JA: Did you learn why these plants ended up there in the first place?

MA: Most of them were imported – they came over with European settlers – often because they had known medicinal qualities or were edible. Or because they simply reminded people of home or had symbolic significance. The settlers did not know that plants that were important markers of place for them would become invasive colonizers of North American ecosystems. It is true, however, that colonialist nations would deliberately plant their seeds around the world as a kind of statement of domination. Conversely, they would also import plants and seeds from their colonies, especially for potential financial gain. Ecosystems are complex and so are the stories around their disruption and homogenization.

JA: I understand that the herbarium piece and other works in your exhibition led to a follow-up project – a rewilding of your back yard.

MA: One of the things that struck me while working on “In My Own Back Yard” was that even though I never used chemicals, my yard was clearly unhealthy. The shagbark hickory had died and the lawn was full of non-native plant species. In the fall of 2019, I hired an expert who rewilded my yard with plants that belong there: for example, purple coneflower, different species of milkweed and goldenrod, and ferns and asters that are all native to this area. In effect, we now have a nature preserve in our back yard. It has become a really important space of inspiration for me, and I spend a lot of time there.

JA: Many different creatures must have been drawn to this place since the rewilding. How are you tracking or cataloguing these changes?

MA: Mainly, I started taking macro photos of the insects in my back yard, and I quickly became very fond of them. It’s like going into another world and the work I do there has almost become ritualistic: a ritual practice of paying attention that I engage with. I write poetry that informs my art and share my photography on social media as a way to invite people into the experience. I want everyone to learn to love these beings as much as I do. Google most insects and your top hits will be extermination companies, which just reinforces the idea that we should be afraid of them. And now we have problems with our pollinators disappearing – some people call it the insect apocalypse. We need insects. They are a critical part of our ecosystems.

JA: A recent William Kentridge exhibition at the Royal Academy in London included his film installation Notes Towards a Model Opera (2015). Among other insights, it emphasized the environmental significance of each creature, however negatively we might at first view them. He referenced Chairman Mao’s The Four Pests campaign which aimed at eliminating rats, flies, mosquitoes and sparrows. The sparrow cull caused locusts to proliferate and destroy harvests, contributing to the ensuing famine that cost at least thirty million Chinese people their lives. Considering the ecosystem from the perspective of food and feeding, and our ongoing struggles to create environments that best fulfil the needs of all, begs the question: What have you learned from your intimate observations of insect behaviour, and insect-plant symbiosis?

MA: I approach my yard, not as a scientist, but as an observer and I’ve noticed a lot of things. One is that because our rewilded yard was designed to be a balanced ecosystem, we don’t get infestations. Japanese beetles, for instance, are everywhere in Southwestern Ontario and they skeletonize whole yards. Our yard gets some, but never in numbers large enough to do damage. I also watch creatures like caterpillars. In one small area of our garden, we have some herbs and vegetables, including parsley. This year I documented the eastern swallowtail caterpillars going through their different phases of development. They would choose one parsley plant and mow it down, but, remarkably, they always left enough so that it didn’t die and always came back. I watched our tomatoes because people complain about how bugs get at them but I have observed that in a healthy garden, insects will decimate one tomato in a clump and leave the others.

JA: So we might say that you have grown a studio which you both tend and attend to with tremendous energy – and of course, etymologically, studio comes from the Latin studere which links practices of studying to expressions of zeal.

MA: It’s a studio, a laboratory, a church in a sense – a place of reverence and connection.

JA: And a place of wisdom because it’s revealing these patterns that we really need to pay attention to. There are besetting problems in our world connected with resources and the problem of who has what and who takes too much – getting the balance wrong. The problems of addiction and overconsumption – not knowing when to stop; not having the capacity to let things be.

MA: And leaving some for others. We need to get away from the idea that we have to take as much as we possibly can. I wish that everybody who owned a business would watch eastern swallowtail caterpillars develop on a parsley plant.

JA: As you have photographed your yard and its creatures, you have entered into a quite different, non-competitive, non-hierarchical economy, one in which transformations in how we perceive and learn have a profound cognitive, emotional and behavioural impact. In her book, World Spectators (Stanford University Press, 2000), Kaja Silverman reflected on how non-verbalising creatures and things communicate and how we all can be reshaped as we attend to these communications. As a phenomenologist, this interests me profoundly. I like to think of these encounters as occurring in what I call the self-showing world: a world in which dualistic models have been progressively dismantled. I believe that close looking – including technologically-assisted close looking – can break down enmity. When we experience ourselves as self-showing entities in a self-showing world, something extraordinary happens: a dismantling of forced boundaries between the human and the natural world which was created to be loving and to be loved by us.

MA: Some ecologists now use the word, love, which is at the core of all this. And there is a connection between love and place and the sacred.

JA: You have said that perceptual immersion in your garden studio led to a loss of fear about aspects of the natural world you originally regarded as horrific and ugly. Through your photographic work, you’re starting to inhabit this strange and unfamiliar world; it is welcoming you and seems to be recognizing and acknowledging you.

MA: That’s exactly how it feels. I now talk to plants and to insects a lot. I write poetry about them. I tell them they are beautiful and am no longer afraid of them. I was looking closely at bald-faced hornets and noticing how beautiful they are. Google has pages of warnings that they are dangerous, but they’re dangerous when their habitat is being invaded – when they’re not respected. There has to be reciprocal respect: I haven’t been stung yet.

Beauty and the sacred

JA: For you, the “ugly,” “frightening” or “dangerous” seems to have become beautiful. It interests me that in the 21st century there’s been a resurgence of interest and respect for this notion of beauty that was so denigrated during the 20th century. Now theorists (Lars Spuybroek, Joke Brouwer and others) talk about the idea of a vital beauty, not a stagnant notion of beauty where everything is perfectly symmetrical; but a kind of vitality and energy. This seems akin to what you are experiencing, not beauty as something static – perfected and composed – but a beauty of demeanour: the way things operate and relate when they are allowed to become intricately balanced and aware.

MA: Yes! For example, I recently read that there is an electric component that attracts bees to particular flowers. Recognizing the relationship between beauty and vitality and energy is crucial.

JA: How have these revelations affected your broader reflections on aesthetics, especially from the vantage point of faith? Your experiences of beauty here seem to function as deeply affective, and effective, gateways into realms we might want to describe as divine, realms that we might otherwise be closed to, or simply miss.

MA: I’ve always been attracted to the thin places, liminal spaces. I hadn’t thought of beauty as a gateway, but why not? I always feel that my yard is a liminal space. And I believe that one of the problems today is that we no longer see the sacred in the natural world. If we saw a wild space as sacred, we would be far more thoughtful about how we interact with it. Would we be so quick to destroy something we consider to be sacred?

Eucharist: in gratitude

JA: And, of course, beauty is a form of sustenance – and this recalls our earlier discussions. You grow literal foodstuffs in your studio/garden, but this place also feeds you spiritually.

MA: Yes. For years, I have been interested in that deeper nourishment. I have used the Eucharist as a theme in a number of works because the whole ritual around the Eucharist is one of spiritual nourishment and gratitude. In 2013, I created In Communion, which shows a metaphorical connection between the eucharistic elements and symbols of community, hospitality and nourishment, represented by using beeswax and honeycomb. At that time, I had just begun to make the connection between the holy and the wild.

The kind of nourishment my yard gives me has opened up new pathways to human connection as well. There are many who seek a way forward as people of faith in a hurting world. I have become involved in the Wild Church movement and am looking back at my faith tradition with a new lens and a deeper understanding. I have begun to call my art practice transdisciplinary because, not only does it draw on different disciplines, it takes on forms that are traditionally assigned to different practices, that may not always look like art: a poem, a psalm, a scientific paper, a song, or a conversation. In my practice, separate disciplines drop away and process becomes more important.

JA: Your work doesn’t shy away from acknowledging pestilence and death. I’m interested to hear how those themes fit into your practice.

MA: To think of the natural world as all sunshine and happiness is a shallow understanding of reality. So, I pay attention to the darkness out there – things like predation and again, it seems that it is never excessive. Death is part of the balance, as is darkness, and the underground. What goes on underground is phenomenal and generally ignored. Scientists are finding out more about communication networks through mycorrhizal fungus – we were unaware of this until recently, yet it is essential to how life is sustained. I think we need to reclaim the word “mystery” when it comes to our understanding of God and the created world – the more I think I know, the more I realize I don’t know – and we need to approach the complexity of the world with that kind of humility or we will continue to destroy.

JA: Speaking of destruction, you did a series of works about the loss of native ash trees. Why was it important to approach this work by creating rituals of mourning for them?

MA: Rituals are important and I feel that most of our lives lack rituals – especially around death and mourning. For this project, I postulated that if we properly mourn species that are lost due to human actions, we might take more care to prevent such losses in the future. So, I created mourning objects, wrote poetry, crafted symbolic “shrouds” for dead trees, and even held a memorial gathering for the community. This all circles back to gratitude. When we lack that eucharistic sense of gratitude and communion, we become disconnected from the natural world; we disrupt the balance.

Get the latest issue in print or subscribe for the next three.