Walter Hayn lives in Penge, London. Alongside his practice as a painter, he is a part-time school art teacher and works for his church, Ichthus Christian Fellowship, with particular responsibility for children and artists attending the church. Jorella Andrews speaks to him about his work.

Jorella Andrews researches and teaches in the Visual Cultures Department, Goldsmiths, University of London. She also works with Walter supporting artists in the church.

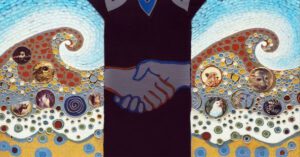

Please visit Instagram.com/walterhayn or walterhayn.com to see more of Walter’s work.

Jorella Andrews: The studio in which you’ve been working since 2019 is a large, square room, with windows on all sides. Remarkably, it’s located in what was a long-disused, debris-filled church tower of Penge Congregational Church, and it is reached by stairways that become more precarious the further up you go. What has working in this space made possible?

Walter Hayn: I had for years been working from a studio-room in my home, and quite apart from contending with the strong smell of oil paint and turpentine, I’d started using bitumen and silicone rubber whose fumes are even more hazardous. Previously also, space constraints meant that I had to put the most recent canvas away and then haul out another from the growing pile. Having this studio has meant that much of my work in progress is exposed and hanging around me like a developing exhibition.

Another thing I’ve loved about this studio is its high ceiling, and that to me has a psychological impact; no longer feeling cramped, it allows me to aspire higher as it were.

JA: In our conversations over the years, the longing to reach higher in a spiritual sense has come up again and again; this idea of being able to push your head up above the canopy and see far into the distance. And now, here you are, in this studio which literally is a high place. But I know that what has become apparent to you is that if this studio-as-high-place enables far-seeing, it has become more about internal rather than external vision, hasn’t it?

WH: The desire to see into the distance effectively has always been important to me. On many levels. During my two years of military service in South Africa, I did patrol work in the war zone of northern Namibia, whose flat landscape left an indelible impression on me, and I learned a lot about accurate, long-distance seeing, partly from the critical need to see potential enemy threat. But, the internalised long-distance seeing that I’m doing in the studio now has something to do with where I find myself at this juncture in life. I have experienced three epicentres; I grew up near Durban, South Africa (including, as a young adult, the years of political transition of the 80s and 90s), but also have strong German family connections to a particular area of Germany (Vogtland); and now I have lived in London for twenty-three years. There might be something about being high up to see how those things do and perhaps don’t intersect. This has been, of necessity, an isolating experience, bringing me into sharp focus with myself … and with my Creator.

JA: Like an attempt to get your bearings?

WH: Yes, and a desire to explore how my earthly identity echoes and coalesces with my spiritual identity as a citizen of the kingdom of heaven. The idea of seeing from the “highest place” which is God’s rightful position in one’s life (as in Jacob’s dream), has been a thread running through my work since my student days.

It is however quite ironic for me to have a high-up studio because I’m quite scared of heights, but at the same time it reminds me of a watercolour painting I did in June 2020, Icarus’ Surrender, depicting a helicopter whose pilot, like a modern-day Icarus has managed to escape not the island of Crete, but the earth’s atmosphere itself. When the rotors become useless because of a lack of air, however, rather than the technology disintegrating (like Icarus’ melting wings), the craft and its pilot surrender to the gravitational forces of heavenly bodies. The painting gives me the strange sensation of losing control and of losing one’s roots and proper environment somehow, but there’s a sense of liberation in that surrender at the same time. This is the space of art making, which for me has to be an adventurous act of faith. Neither God nor art allow us to feel too settled for long!

JA: This sense of the aerial with its insights and dangers seems to permeate much of your work. So many of the paintings that I’m looking at now, in your studio, have that feeling of being aerial views, and there is also a sense that different works are combining. In fact, you have combined some of them. It’s almost as if you’re piecing things together and constructing a more extensive and complex map …

WH: You know, I was just working on individual paintings. I think I just had a bunch of small-format canvases which I’d bought from the same shop, all the same size, and I just worked on them independently.

Many of them had biblical themes to start with, but later they became abstractions. I felt the need to constantly keep processing them and then it was almost as if the different canvases grew closer together, magnetically, and called to each other. As I was playing around pairing the paintings in different formations, linear marks on the edges were converging and then it seemed that they couldn’t any longer exist apart from each other.

JA: It’s fascinating. It’s almost like a kind of geography emerging, and you’re not orchestrating it. Like tectonic plates coming together purposefully and very naturally.

WH: Sometimes I get disillusioned with my work because of the slowness of it. But when things like this happen I realise that I’m on a journey, and that I’ve got to keep going and, bit by bit, allow it to come together of its own volition.

JA: About this journey … You talked about it just now as a journey that ends up being more effectively expressed in abstract terms – in non-literal terms – although of course the abstract forms of grids and crosses that keep emerging in your work embody and express the absolute fundamentals of divine grace as this is understood in Christian contexts. No cross, no connection.

WH: The more I think about it, I reckon that the more my images have to do with the internal landscape that I find myself surveying, the more abstract they are but also the more visceral and energetic. I want people to feel what that inscape is like.

JA: It seems to me that the abstract marks register – or provoke? – internal force fields. We get a sense of where things are coming together and where things are breaking apart, where they are fitting and where they are not.

So abstraction in your work isn’t a matter of Scripture becoming generalised and impersonal. It is actually about it becoming incredibly real. It’s getting embedded in your inner life as structures and energies that are having effects. So maybe it is about the working of these truths in your being, and how they are functioning, and what they are rearranging, and how they are causing certain things to encounter each other? And that must be both an unnerving and a reassuring sensation. When you feel that there are all of these inner incompatibilities – and probably everybody feels this on certain levels. But again, it is the cross that unites without forcing connections between things. The bigger or more difficult the gaps, the bigger and more robust the cross becomes.

WH: Yes, just as the identity and nationality schisms we spoke about earlier are healed under the cross. Furthermore, we are confronted with the spiritual battle spoken of in Ephesians 6:12, that simply can’t be boiled down to a single figurative image. My painting Malta (still a work in progress) started off as an overt depiction of that moment when the apostle Paul is shipwrecked on the island of Malta, gathers firewood and is bitten by a viper. But it is no longer very figurative. You can still see the fire somewhat, and the turbulence of storm waves, and … I have the feeling that Jonah and his fish could be in that distant sea … you know, that struggle, that internal struggle, and opposing forces just trying to take advantage of it. As I have grappled with the concept of the power of the cross at work in the situation, and with the threat of the Serpent reaching through the metanarrative of the Bible from the garden of Eden to its fiery destruction in Revelation 21, the painting has become very layered.

It seems that our discussions of the studio as a high place, and what this means, also plunges us into the depths. The act of far-seeing is both an attempt to gain fresh perspective and new bearings but has also resulted in a necessary and repeated homing in on the inscape.

JA: Your work has developed these incredible, entangled, even embroidered surfaces. With these entangled works, you’ve stepped right into the scene, and it is also in you. So, there’s entanglement and there’s also the high place where you can start seeing how things are gathering and where they are converging – or not – and where the grace is. Your studio has enabled both kinds of ongoing perceptual shift.

WH: For me, the thing that pulls all of this together is that God is in all these places. Just as God is in the ‘“gentle blowing” voice, so he is with Jonah in the depths of the sea, and he is the eagle from Deuteronomy 32 who sees far and sees everything and bears us up with him.