Walter Hayn is an artist and a part-time art teacher who grew up in South Africa, but now lives in South East London. He and Gert Swart have been friends since meeting in 1989 at a Christian Arts Conference led by Craig Bartholomew.

Gert Swart’s artistic career has spanned over forty-five years. Born in Durban, South Africa, he began pursuing art in 1976 in the midst of a short career in the Durban Municipality Health Department. During this period, he was exposed to the breadth of racial inequality imposed by apartheid, observing how people lived and worked across all sectors of society. His art has very often sought to address and redress the outcomes of pain and injustice inflicted by the Nationalist hegemony; and as the power base shifted in the foment before and after Nelson Mandela’s release from prison in 1990 and the 1994 elections, Gert was creating a body of work which exposed and commented on the pain and hopes of those years. His landmark exhibition at the Tatham Gallery, Pietermaritzburg, in 1997, brought this body of work together. Gert has continued to work despite overwhelming physical-health setbacks. He currently lives with his wife, Istine, in Pietermaritzburg.

Walter Hayn: The title of this series, In The Studio, immediately brings to mind the physical workplace of the artist, and I have been remembering my regular visits to your studio over the years since we first met. You have worked out of four or five different studio locations since 1989, the year of my first visit. What does “in the studio” mean to you?

Gert Swart: I guess to be in the studio implies that I must be in the zone: a coming together of pure inspiration and the will to manifest whatever that is ― no easy task! It is true that over the years I have had many studios but my primary studio has always been my “inner studio.” For me this is the internal space where I conceive my work and a place where I have harboured the notion, since preschool days, that I was destined to be an artist: it is my sacred space.

Although sculpture making is largely a solitary pursuit, for me to be “in the studio” implies a huge indebtedness to friends, family and many others who, in a very real sense sustain me there, especially Istine, who has sacrificed so much for me!

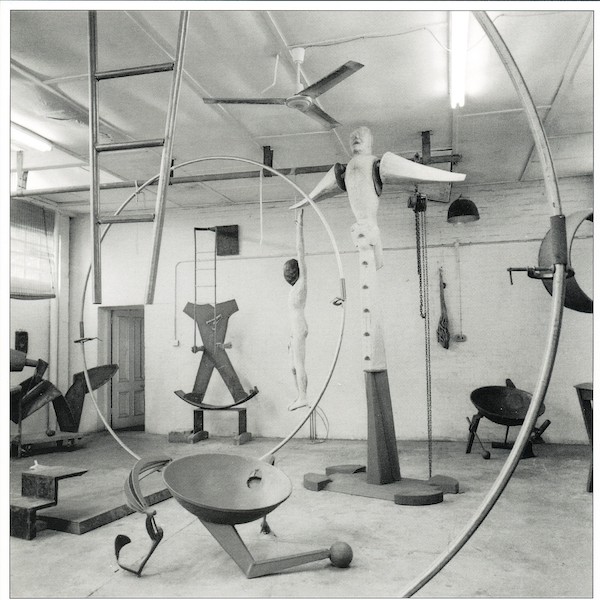

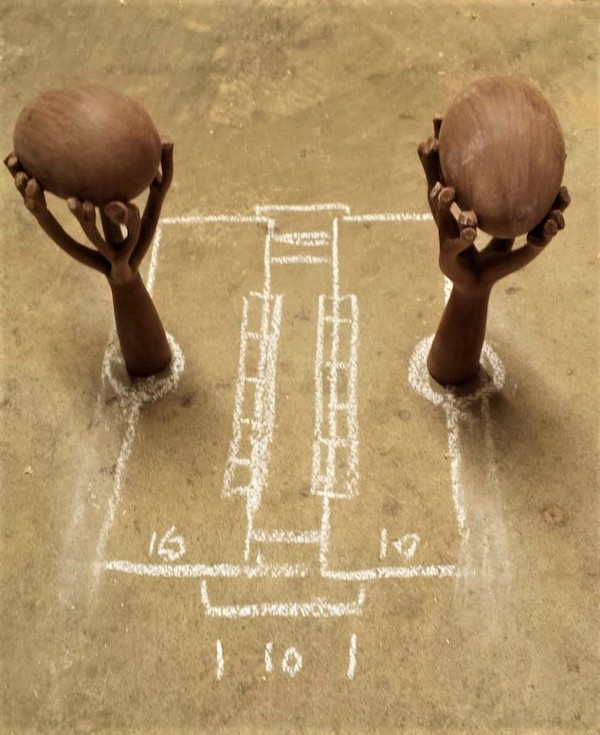

WH: Entering your studio has always been an exciting experience for me; to discover what new sculptures you have been working on, but also, (did you know this?) slightly disorientating. The strong smell of freshly-cut wood and other underlying odours like machine oil and perhaps varnish hit first as I try to come to terms with my surroundings. The eye immediately looks for order, and I always seem to locate your reassuring racks of lined-up chisels (SO many chisels), or perhaps the shapes of large familiar and intimidating power tools. There is a fine layering of sawdust causing unlikely objects to blend into one another: tables, of all sizes, strange metal clamps, fans, sculptures in various stages of completion, and shelves stacked with wood…. and then taller sculptures, behind yet more sculptures, peering out. There is no doubt that this is an industrious workspace, but definitely not of the “factory” kind. There are hand-written signs, note scraps and scribbled chalk drawings on the concrete floor. All of this leaves one with a sense of magical possibility, but also mystery.

What does your physical studio mean to you?

GS: Thank you for reminiscing about my various studios: you are quite the observer! To be honest — and this might shock you — once I close a studio door for the last time I never look back. The physical studio has always been just a space where I bring to fruition pieces conceived in my “inner studio.” Although I spend an inordinate amount of time in my physical studio, for various inexplicable reasons, I seem to have a love/hate relationship to it. I think it is this kind of tension/uncertainty that helps me press on and not get caught up in a sentimental approach to sculpture making.

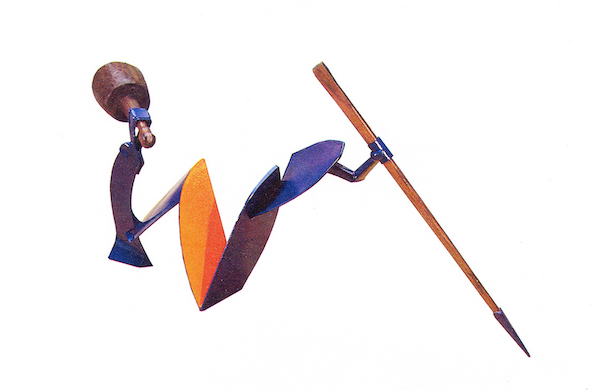

Perhaps my artwork Should a Sculptor’s Mallet Inscribe a Circle? could, to some degree, help explain what I am trying to say. The mallet is held at a distance from the pointed scribe by means of a rigid concertina-like structure. This creates the illusion that if it were to contract sufficiently, it would enable the mallet to fulfil its function as the motive force that describes a circle — the symbol of perfection. But in reality, this never happens and each attempt at inscribing a circle gives rise to sculptures that are by no means perfect. These artworks become symbolic manifestations of the various stages of my journey and describe how I have been “working out my salvation with fear and trembling” in my physical studio. They also function as signposts, marking the journey and acting as pointers directing me ever onwards to the Perfect One: Christ! Such an approach does not allow me to rest on my laurels after completing a work but compels me to continue my pilgrimage, regardless of the feeling that, at times, it may appear to be a relentless pursuit after the proverbial carrot: such is the elusive nature of art this side of perfection!

WH: Through the years I have been aware that your ‘’unsentimental approach’’ means that you will without hesitation, chop into pieces a seemingly complete sculpture which is not “working” in your eyes and use the parts in new or other progressing works. This process suggests that the ideas for your sculptures are constantly evolving or on hold, waiting for the right “moment,” and that some pieces may take years to bring to fruition. When I visit your studio, the works in progress seem to stand in the wings, ready to be worked on or subsumed, but they certainly catch the visitor’s imagination: “What are those dangerous spikes? What are those incongruously ‘soft as butter’ wooden forms?” One becomes conscious also that there are many uncomfortably realistic carved human limbs and faces, wooden birds, snakes and other creatures, all silently looking on — parts of one sculpture or another, like props from a crazy parade or the sculpted icons in an overcrowded chapel. Finally, I notice that one or two pieces have “centre stage.” The newest or current work in progress! How do you determine which pieces you are going to work on next and can you describe the process by which a piece comes together?

GS: Many people have asked me this question and quite frankly there is no easy answer — the choice of “next” depends on so many variables, such as sourcing the right materials and aesthetic problems that are solved over time.

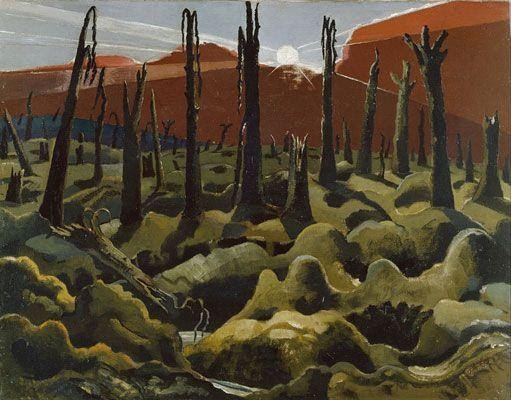

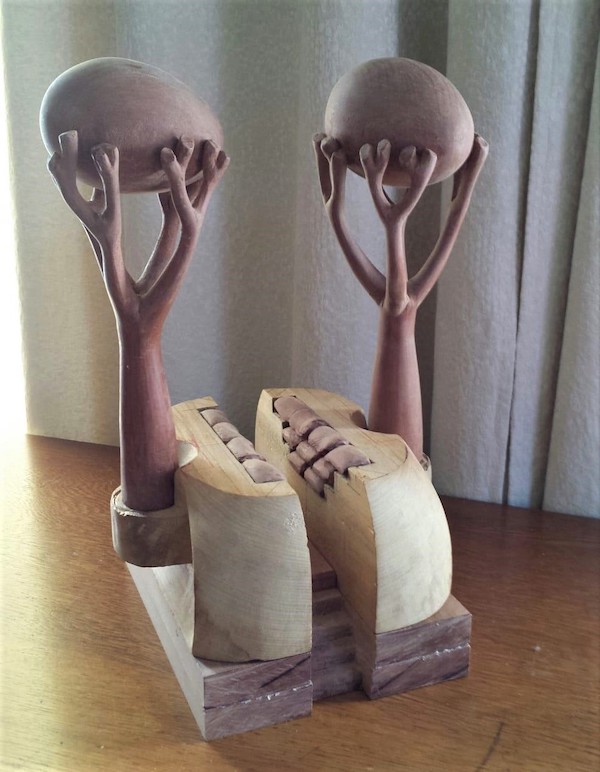

Let me try to answer the second part of the question by talking about a work in progress: the one that appears in part as a drawing on my studio floor with the two sculptural forms. I started carving these forms in 2018 as I had a desire to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the end of WW1. I have always been deeply moved by Paul Nash’s WW1 paintings, especially the sheer irony of his We are Making a New World (1918). I carved, out of red milkwood, two pollard trees that reference Nash’s painting. Each of these trees nests a large, fragile egg — the future!

In 2019, I conceptualised and then blocked out a base in yellowwood for the trees that needed to evoke a WW1 slit trench and its characteristic sandbags. It was only recently (2021) that I was able to find a suitable piece of assegai wood to make the bottom platform. The three types of wood I used are indigenous as I wanted this piece to speak specifically of the great sacrifice many brave South African soldiers made, far from their homeland, during the fierce WW1 Battle of Delville Wood. The title of the piece is: Revisioning Humpty Dumpty, after Paul Nash’s “We Are Making a New World (1918).”

WH: Much of your work is birthed out of a deep empathy with the suffering and disenfranchised peoples of South Africa’s past, but also the tectonic shifts and torment caused by horrors on a global scale, as in your Revisioning Humpty Dumpty…. In my own pondering over many of your pieces, I have found that you never gloss over or try to minimise the pain of the injustices (and human failings) that you allude to, but your desire to seek healing infuses your work with grace but also a call to repentance. Your attitude reminds me of the healing that can come when we “Rejoice with those who rejoice, and weep with those who weep” (Romans 12:14). In this context much of your work is therefore also about transformation and renewal which are profoundly Christian concepts. How would you describe the way your faith has spoken to your concerns in the past and how do you find it inspires your work now?

GS: I am going to answer your question in part by quoting the American artist, Philip Guston, whom you made me aware of many years ago: “What kind of man am I, sitting at home, reading magazines, going into frustrated fury about everything — and then going into my studio to adjust a blue to a red!” I for one am grateful that Guston “went into his studio.” His work is profound and exposes the dark side of the American Dream.

Now to answer your question: Ever since becoming a Christian, that metanoia moment in my life meant that although I had been “turned around in repentance,” my physical reality/history had not changed, but from then on it enabled me to see things differently — through the eye of my heart — and that such a redemptive approach to the human condition was the only true healing balm in answer to the big question: “How then shall we live?” And, what kind of emissary of God would I be if I did not make art that goes some way to bring freedom, hope and love to my fellow human beings and that, by the grace of God, is how I wish to continue in faith to make meaningful art.