Michael Shipster, CMG, OBE, is a former British diplomat whose overseas postings included the Soviet Union, India, South Africa and the US.

When I was serving as a junior diplomat in the British Embassy in Moscow in the early 1980s, the Soviet Union was sometimes rudely described as “Upper Volta with missiles”: a country we took seriously only because of one thing – its possession of nuclear weapons and capacity to destroy its enemies anywhere in the world if it was enraged or confronted.

Sure, it was by far the largest country on the planet, with one-sixth of the land area; it possessed the largest and most powerful armed forces; it had sent the first man into space; it had created some of the most ambitious construction projects on the planet – the new trans-Siberian railway for example; it could justifiably claim to have won, at huge cost to itself, the decisive victory over Nazi Germany after Hitler invaded in the Second World War. From its citadel in the Kremlin, just across the Moscow River from my office in the British Embassy, the USSR radiated power to all corners of the world. With the largest and most ruthless security services, the formidable KGB, it intimidated and controlled its 250 million citizens across fifteen republics, independent in name only, that constituted the “Union of Soviet Socialist Republics” (“Four Words: Four Lies,” as diplomatic wags would sometimes say). Since the end of the Second World War it had controlled vassal states on its borders through client communist parties modelled on the Soviet Communist Party. It had brutally intervened whenever those régimes stepped out of line or lost control over their citizens.

It excelled also in “soft power” (albeit a term not invented then). Across the non-aligned world, Moscow competed with Western capitalism for hearts and minds and worked tirelessly to promote socialist transformation. As a projection of its values and proof of the superiority of its own system, its athletes frequently topped the table of Olympic medals, and its ballet dancers and musicians captivated world audiences even as KGB chaperones tried to ensure none of its stars defected to the West while on tour.

Below the surface there were serious flaws and weaknesses in this military, economic and ideological powerhouse. Its vision and version of socialism was bankrupt and increasingly seen as a sham both at home and abroad. Its octogenarian, sclerotic and isolated leadership had run out of ideas and vision. Its economy was riddled with waste, corruption and false accounting. In terms of most international measures of GDP, it weighed in somewhere between Italy and France. But what it did have, and made other nominally more powerful and successful countries and blocs – the US and Western Europe for example – sit up and listen when there was disagreement and confrontation, was nukes. Lots of them, more than anyone else’s, the biggest and most destructive. The avoidance of conflict which might escalate into a full-blown nuclear war, endangering the planet itself, became during the Cold War one of the principal objectives of international relations and foreign policies of Western countries, including Britain.

The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 and the transition of its fifteen constituent republics into fully independent states in effect brought the Cold War to an end. We – the West – had won. Victory without war, something to celebrate. Those Soviet republics that nominally had nuclear weapons – Ukraine, Belarus and Kazakhstan – voluntarily repatriated them to Russia in return for security and territorial guarantees. In terms of land area, Russia itself shrank to its smallest size in over three hundred years. In the 1990s it then descended into a period of economic chaos and bandit capitalism as crooks and former KGB officers stole and squabbled over the division of the spoils. Pensions were wiped out, millions of its people were impoverished, Russia’s status in the world was diminished, its claims to offer a blueprint for economic development, social justice and human happiness utterly discredited. In the West we breathed a collective sigh of relief. Russia, the old bogeyman, had been humbled. We could continue to buy their oil and gas, build the pipelines that would bring the gas to us, and in return sell them the goods they needed and could not produce themselves. We would get richer; most Russians would get poorer. The new masters of Russia – the oligarchs – would be welcome to spend their obscene new wealth in our countries on mansions, yachts and football clubs, educate their children in our élite schools and we would get along fine. As long as their nukes were stored safely and were unlikely to be needed, we could sleep easy at night.

At least that was the hope. But history has a way of confounding the best intentions and most confident expectations. Now, in 2022, thirty years after the end of the Cold War, some of those old dragons have been roused from slumber. Following the invasion of Ukraine, we seem to be in the grip of a new Cold War, one just as dangerous. What on earth happened? How did we let things get so out of hand?

It did not take long after the start of the war (or “Special Military Operation” as Putin still insists on calling it) on 24 February for it to become apparent that this was one of those “hinges of history”: a watershed moment, a sea-change, an event which quite simply changes the world, after which things will never be the same. Of course, the invasion did not by itself change the world. It was more a culmination of growing dangers and tensions, apparent but not taken sufficiently seriously over the previous two decades, bringing unresolved historical perils into sharper focus. Those perils now threaten international relations, the world’s economic outlook and indeed even the security and future of the planet itself.

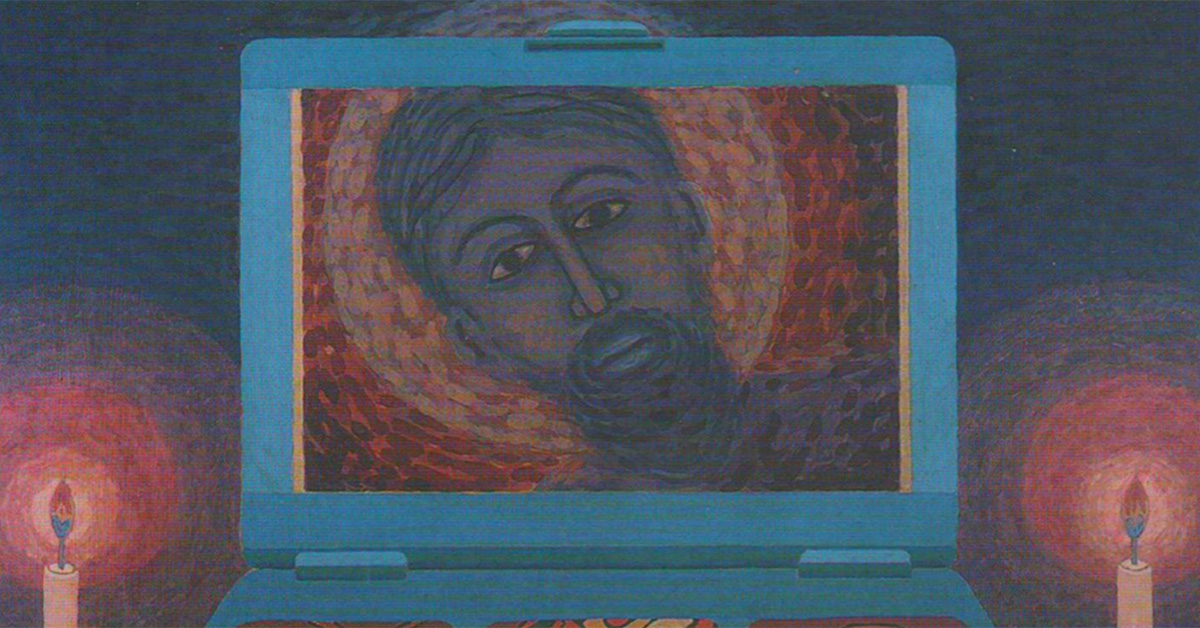

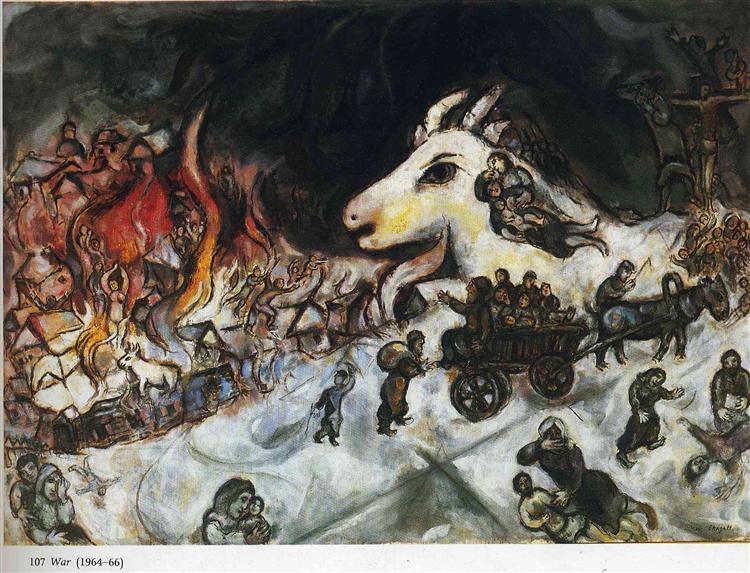

In the last century we have seen similar such hinges of history, events that change the world but initially seem to take people by surprise. One undoubtedly was the assassination in 1914 of the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, Archduke Ferdinand, in Sarajevo. Few could have immediately predicted it would be the trigger for the outbreak six weeks later of the most destructive war the world had yet seen. Lasting four years, it devastated Europe, caused over forty million casualties and ushered in revolutionary change – including the Bolshevik coup in Russia in October 1917, the overthrow of the Tsarist empire and five years later the formation of the Soviet Union.

Another was the surprise Japanese air attack on the US fleet in Pearl Harbour in 1941, which brought the Americans into the Second World War. Among other consequences, it led four years later to the dropping of atomic bombs on Japan in 1945 to bring the devastating war in East Asia to an end, but also to usher in the nuclear age. Eighty years on, we are still living fearfully in the shadow of the mushroom cloud, with the risk of global nuclear conflict arguably at its highest level now, in the wake of the war in Ukraine, than at any time since the Cuban missile crisis in October 1962. It is not accidental – a phrase former Soviet leaders were often fond of using – that in one of Putin’s recent menacing threats to the West, he should cite the US first use of atomic weapons against Japan as an historical precedent that would justify Russia’s recourse to such weapons now in its war with Ukraine.

A third hinge of history – which contributed to where we now find ourselves in our confrontation with Russia – was the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979. At the time it was viewed as yet another Cold War gambit, capitalising on perceived Western weakness in pursuit of Moscow’s long-cherished ambition to secure a warm-water port. But it turned out to be much more than that: a strategic miscalculation which hastened the collapse of the USSR only twelve years later. While few outside Russia mourned the Soviet Union’s demise, Putin, the modern Russian Tsar, has described it as the “greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the twentieth century,” and the “demise of historical Russia.” Right there, we can see its critical significance in the context of the current deadly impasse in Ukraine.

So far the war has not exactly gone to plan for Putin and his generals. They expected Ukrainian resistance would swiftly collapse, the inconsequential President Zelensky would surely flee abroad and Kiev would soon be occupied, opening the way for a pliant puppet leader to be installed. The West would no doubt make a fuss, but would eventually accept the fait accompli, new “facts on the ground,” as it had over the annexation of Crimea in 2014. There would no doubt be further sanctions against Russia, but these would have little long-term impact. Business – especially trade in energy and minerals – would continue. Russia would have decisively demonstrated its strength and importance in the world and go some way towards re-establishing its rightful hegemony over the states of the former Soviet Union.

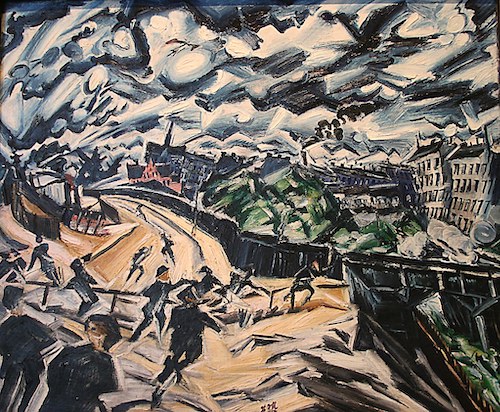

Instead, the government and people of Ukraine have shown spirited defiance. Moscow’s plans to capture Kiev failed dismally. Western support for Ukraine and sanctions against Russia have been more effective and better coordinated than Moscow anticipated. Russian forces, especially unmotivated conscripts, have performed poorly in battle against determined Ukrainian regulars and volunteers fighting in defence of their homeland. Russian casualties have been higher, territorial gains less. Until the summer, a costly stalemate on the battlefield seemed to have been reached. But recently Ukrainian forces have gone on the offensive, retaking territory in the east of the country, and attacking bases and supply depots well behind Russian lines, including in Crimea. The most spectacular attack was on the Kerch Bridge connecting Crimea to Russia – a pet project of Putin himself – which stung Russian forces into launching dozens of ill-aimed missiles against targets in Ukraine.

Putin has meanwhile been forced to acknowledge that existing Russian forces are insufficient to achieve the original military aims and has announced plans to conscript an additional 300,000 into the army. This has prompted unprecedented protests against the war on the streets of Russian cities and the flight of thousands of young men to neighbouring countries like Georgia to escape the draft. In order to shore up its shaky hold over territory already seized, Russia organised hasty – and widely condemned as sham – referenda in the eastern provinces in favour of complete incorporation into Russia.

It was when Putin announced to the Russian people the results of these votes that he made the menacing warnings that further attempts by Ukraine, with the assistance of NATO, to retake its former territory would henceforth be regarded as an attack on Russia itself, and therefore liable to a full military response in defence of Russia’s now enlarged sovereign territory. This was understood internationally as a clear sign that Russia might resort to the use of nuclear weapons. To underline the threat, Putin added “I’m not bluffing.”

The war in Ukraine has already had profound and world-changing consequences. Beyond the devastation of the country itself there is the global economic impact through widespread recession and inflation, exacerbated by Western sanctions against Russia and use by Moscow of the energy tap in turn to put pressure on European countries dependent on Russia’s oil and gas. Many countries, especially in Africa and the Middle East, critically reliant on the import of Russian and Ukrainian grain, are facing massive food shortages, and price rises. This in turn will increase migratory pressure from poor countries to rich. We can also expect to see as a result of the war a fundamental restructuring of security arrangements and military deployments in Europe, including (to Moscow’s dismay) the expansion of the NATO alliance; and a heightened risk of further conflicts elsewhere in the world, especially in East Asia (Taiwan) and the Middle East. After 24 February the world order has become more unstable and unpredictable.

So, back to the question: how have we got to this dangerous pass, with no clear exit and some truly catastrophic possible consequences? For the answer we must reach back several decades to the end of the Second World War and the ideological and military divide between East and West that followed. No one side has been able to claim consistent adherence to the UN-endorsed rules-based principles of non-aggression and non-interference. Soviet invasions of East Germany (1953), Hungary (1956), Czechoslovakia (1968), Afghanistan (1979) attracted widespread condemnation at the time. But in turn Moscow could cite military actions by the US and the West: US intervention in Vietnam (1960s and early 1970s) and Central America in the 1980s; NATO peace-keeping (or interference, depending on your point of view) in the Balkans (1990s); and more recently the US invasion and régime change in Iraq (2003); military intervention (and again régime change) in Libya (2011) – to name only a few.

In 2008, as a riposte to Georgia’s flirtation with NATO membership, Russia occupied parts of North Georgia. In 2014, after the overthrow by popular uprising of Moscow’s Ukrainian ally President Yanukovych, Russia seized Crimea and invaded parts of Eastern Ukraine. When in 2015 Moscow intervened in Syria in support of the Assad régime, there was again a mixed international reaction, but no effective UN response; and despite the crossing of US and Western “red lines” (including use of chemical weapons against civilians) the West ducked punitive countermeasures. No wonder then in 2022 Putin was confident he could again attack Ukraine with impunity.

Russia itself has already paid a heavy price for the war, with even bigger bills to come. Moscow downplays the economic impact of sanctions, hoping the West will feel even more pain, leading to willingness to break ranks and ease the penalties. So far the Western alliance seems to be holding firm and as time goes by sanctions will increasingly affect the lives and prospects of the Russian people. Meanwhile the “Russian brand” has suffered lasting damage. Whereas during the Soviet era it could at least make some claims for its brand of socialism, standing against the capitalist West, as an example for the rest of the world, now Russia can offer no such model. While some autocratic world leaders might envy Putin’s brand of brutal authoritarianism, it is hardly an exemplar for other countries to follow.

Russia’s reputation – already scarred by widespread institutional cheating in international sport, a reckless willingness to assassinate its political enemies abroad and lock them up at home, a refusal to abide by the central precepts of the UN Charter and a list of friends that reads like a roll call of the most repressive régimes in the world (China, Syria, Venezuela, Iran, Myanmar, North Korea) – continues to be degraded. Putin likes to tell the Russian people it is the West that is the true aggressor, having long harboured a visceral, even satanic hatred for Russia and its citizens, for its culture, identity, values and historical destiny. The war in Ukraine, he insists, with the support of the Russian Orthodox Church, is actually a holy war of liberation against Russia’s fascist enemies, a wholly justified crusade to reclaim Russia’s historical territorial identity, and right to security. Cowed and half believing their leader, most Russians so far seem to have supported him, or at least been reluctant openly to oppose his leadership. That may now change.

Speaking personally, I am saddened by the enmity that has been whipped up between Russia and the West. Although making friends was made deliberately difficult when I served in the Soviet Union, I have long admired the courage, creativity, resilience, and capacity for friendship of Russians I have got to know. I love the music of Rachmaninov, Tchaikovsky and Prokofiev. I love the richness of the Russian language and especially its greatest poets: Pushkin, Mandelstam, Pasternak, Akhmatova, Yevtushenko. Chekhov, Tolstoy and Grossman are among my favourite authors. Grossman’s Life and Fate, one of the greatest novels of the twentieth century, is full of wisdom and humanity even while describing some of the worst horrors of the era in which he lived. It will be a heavy price for all of us if these voices and artistic works are eclipsed and disparaged by this savage and unnecessary war.

Predicting how it will end – for all wars do end – is not easy. Neither side is backing down or showing signs of weakening and no certain outcome is in sight. This has become a perilous conflict by proxy between Russia and the West, determining not only the fate of Ukraine and the security of Russia’s Eastern European neighbours, but also the future security architecture for the world and our prospects for tackling other long-term existential threats that we face, including climate change.

Putin is unlikely to have a change of heart, withdraw and offer the hand of friendship to his near neighbour. Equally unlikely is that Ukraine will accede to Russian occupation, still less accept annexation. In between are scenarios ranging from the manageable to the unthinkable: from Russia running out of military steam, Putin being replaced by a more pragmatic leader and a lasting deal being agreed; to Putin doubling down on his military gamble, ratcheting up the military stakes, holding the threat of nuclear conflict over Ukraine, NATO and the rest of the world for years to come. At this point the gloomier second scenario appears the more likely.

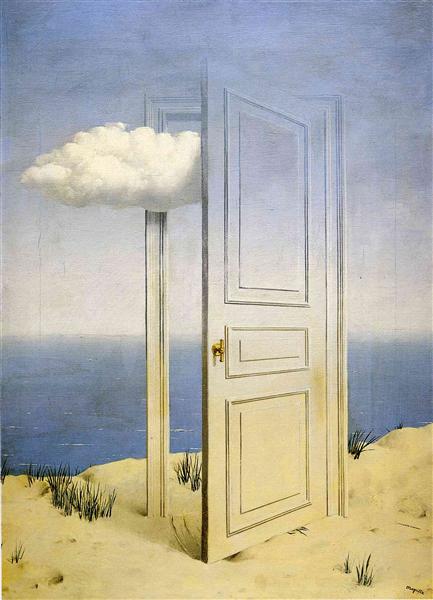

As a hinge of history, Putin’s decision to invade Ukraine on 24 February therefore swings a heavy door. How far and fast it will swing and where it will come to rest remains to be seen. It may be one of history’s ironies that the decision to invade Ukraine may turn out to have equally catastrophic consequences for the Russian state, Russia’s position and influence in the world – and indeed for Putin himself – as the decision by his Soviet predecessors to invade Afghanistan 43 years ago.

Whatever game Putin is playing – whether chess or poker, or indeed his beloved judo – by invading Ukraine, he and Russia have thrown down a high-stakes challenge and revived a new Cold War mindset, with acute dangers incubating in the wings. There can be no outright winners but whatever the outcome the world has been forever changed.

Winchester

October 2022