Jason Fischer lives in Phoenix, Arizona, with his wife and three adult kids, and is a pastor of Heritage Church. Carpentry and photographs by the author.

There’s a resistance growing in the woodworking world. In reality it’s always been there, and I have only recently begun to listen. It’s led by men and women who, with chisel and mallet in hand, are chopping away in defiance against the industrial machine. They speak about the value of handmade furniture built in quiet shops adorned with hand tools and littered with wood shavings. These aren’t just shops, they are sanctuaries because, for these craftspeople, something sacred happens there. They understand that working with our hands is a way to recapture something that appears to be disappearing in the Western world.

I do not have to spend time here explaining the challenges we face with consumerism that is fuelled by large corporations driven by the bottom line. We know it because it’s all around us. We are regularly harassed by planned obsolescence. It mocks us as we struggle to assemble the particle board entertainment centre that will no doubt find its way to the trash heap soon enough. The real kicker is that we are never more pleased to toss it when the time comes because it was never really ours to begin with. We have been reduced to the role of consumer.

One of the voices leading this resistance is Christopher Schwarz, a self-proclaimed “anarchist,” but not in the “let’s wreak havoc” sense. In his The Anarchist’s Design Book, ([Covington, KY: Lost Art Press LLC, 2016], vii), Schwarz argues that our culture has been ruined by mass-manufacturing where things need to be replaced regularly. He writes, “Anarchism in this context is a tendency to build rather than buy, to create rather than consume. You can call it self-sufficiency or DIY. But when you make something that does not have to be replaced in a few years, you throw a monkey wrench into a society fueled by a retrograde cycle” (vii). In other words, making furniture goes against the culture of consumerism where nothing lasts or stays in fashion for very long. I agree with him, which is one of the reasons why I am committed to woodworking.

But there’s more. Schwarz goes on to say that handmade furniture is “‘necessary’ in the sense that we have to make things – anything – to preserve both the craft and our humanity. The history of civilization and woodworking are the same. Making things makes you human” (viii). He is getting at something very important. We are all driven by a longing to find our true humanity. He is expressing the reality that being human is something that can be lost but also restored.

I don’t know where Christopher Schwarz is with regard to faith and Jesus but this is an important part of the gospel and what Jesus came to do: restore all things, not the least of which the humanity of humans. The gospel is clear that we cannot do this on our own. We need the reconciling and restoring work of Christ at the cross and resurrection. But the Bible continually invites us to follow Jesus and play a part in the restoration. Christians have been talking about spiritual disciplines as a way to press into a life in Christ for a long time. They speak of prayer, solitude and fasting to name a few, as ways to live out our identity as humans created new in Christ. Some have even spoken of such practices as acts of defiance against powers that are intent on destroying and dehumanising us. I would like to add “making something with your hands” to the list of spiritual practices because the resistance isn’t merely against the industrial machine, it is against the powers of evil behind our cultural idols.

I believe we were made to make. Look at children! They are constantly making things with anything they can get their hands on. It’s how we learn and grow. Remember the toys we played with when we were kids? There’s a reason LEGO is one of the most popular of all time.

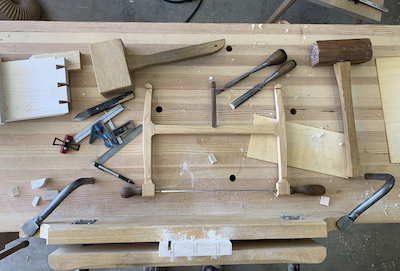

I grew up in a house where working with our hands was normal. I was nine years old when my dad gave me my first saw. It’s a coping saw with a deep “U” shape. The frame is black with a red handle and I still have it. Now, in my mid-forties, I continue to develop my skills as a woodworker. In recent years I have especially enjoyed my foray into the use of hand tools. Yes, electric tools like table saws get the job done quickly, but as I have delved deeper into woodworking, I’m learning that the craft is not just about making a usable piece of furniture as quickly as possible. Hand tools put me even closer to the work. There’s nothing like the feel and sound of a razor-sharp hand plane gliding across the surface of a board. Planing wood, cutting and fitting joints by hand demands more from me than my power tools and because of that the practice is formational. Not only am I developing the particular skills and hand-eye coordination required, I’m learning things like patience, how to enjoy the process, and coping with failure. My definition of perfection has changed as I discover idiosyncrasies that come with handmade furniture. Is a piece perfect because its surfaces are glassy smooth and every angle is within a half-degree or is a thing perfect when it bears the marks of its maker?

The point is that I am discovering a surprising product of working with my hands. It’s shaping me. It connects me with something deep within, a longing to return to work that gives me a sense of vitality and purpose. I am not denouncing a desk job. I have one, and good, God-honouring work happens at desks. But I have experienced a yearning to work with my hands that I cannot ignore. When God placed his human creation in the garden, he placed them there to work, to sweat and get their hands filthy. When God spoke to his people through the prophet Isaiah, he promised them restoration by saying,

No longer will they build houses and others live in them,

or plant and others eat.

For as the days of a tree,

so will be the days of my people;

my chosen ones will long enjoy

the work of their hands. (Isa 65:22 NIV)

A return to truly living as the humans God made us to be includes the work of our hands and the freedom to enjoy it. As people who are being reconciled to God through Jesus and living here and now as his new humanity let us display the goodness of God by making stuff with our hands. One of the things I found interesting during the pandemic lockdown of 2020 was how many people found new hobbies. I think this happened for reasons greater than just boredom. I think that, when given the time, we desperately want to make things. I’ve focused on the merits of woodworking but there is so much more we can try. Bake cookies, paint, crochet, sculpt, learn an instrument, sew, garden … you get the idea. In so doing we are recapturing a piece of what it is to be human. Join the resistance!