The Rev Dr Susan I. Bubbers (DMin, PhD, OCAEF) is the Dean of The Center for Anglican Theology, the Rector of Celebration Anglican Church, Florida, and an Associate Fellow of the KLC. She is the author of Pet Prayers (available at Amazon.com). See also www.CenterATLAS.org and https://courses.biblemesh.com/atlas-theological-center.

The theme of this edition of The Big Picture is “The Nurture of Nature.” One quickly smiles at the fitting literary ambiguity of the phrase. Shall I write about the way we humans are called by God to nurture nature, to care for God’s creation? Or, shall I write about the many ways God’s creation provides nurture to us? Actually, by writing about animals, I will be able to write about both perspectives at the same time. For, when we dedicate ourselves to nurturing animals, God will use that expression of care as a conduit to convey graces of many kinds to us.

Let us consider the idea of “nurturing.” The connotations are many, such as teaching, protecting, encouraging, nourishing, guiding, comforting and loving. Nurturing is providing the context for health and growth, safety and thriving. Read all of these again, and realize that just as we can nurture animals in all these ways, so too can they nurture us in all of these ways.

Allow me to go a step further and posit that not only “can” we humans offer such nurture to animals, but also we are “called” by God to do so. And, as with any form of calling, as we fulfil God’s desires and purposes, we experience his grace and blessings. While much has been written to explicate the biblical theology of creation care and stewardship, here I will emphasize just two points.

First, the biblical theology of stewardship recognizes the role God intends humans to have in regard to his creation. God’s first commission to humans was to care for both the environment and the animals. This sense of purpose was set into humans before the fall, and remains inherent to the imago Dei. As humans fulfil this calling, we are more fully human. The love and compassion and wisdom of Jesus make this all the more possible for Christians. Christianity should be showing the way to the rest of the world about how to care for the earth and all of its creatures.

“Then God said, ‘Let us make human beings in our image, to be like us. They will reign over [radah] the fish in the sea, the birds in the sky, the livestock, all the wild animals on the earth, and the small animals that scurry along the ground.'” (Gen 1:26 NLT)

The New Living Translation of the Hebrew “radah” as “reign over” is a more helpful translation than the ESV “dominion over” or NAU “rule over,” for these have been taken as grounds for opportunistic, even short-sighted and selfish, uses of resources and animals. But, to be an expression of God’s image, selfless nurture and care is certainly the mandate. The kingdom of God is a place of thriving, not a place of exploitation.

The second point I will emphasize in the biblical theology of stewardship is the recognition of the role God intends creation to have in our lives. Creation is often referred to as “general revelation” and is a companion to the “special revelation” of the Incarnation and Scripture. Creation is meant by God to be a conduit through which he communicates his nature, character and purposes, albeit with not as much specificity as through the Word. Through the majesty of creation, God’s glory and goodness are made evident (Rom 1:16–20; cf. Pss 50:6; 97:6). Through the marvels of creatures, God’s graces are also conveyed. God can do anything, and he has shown that he can choose to use animals to convey his will and correction (Num 22), teach sluggards how to be wise (Prov 6:6), be a metaphor for his own divine being and doing (Ex 19:4; Ps 91:4), and serve in teachable moments to further discipleship (Matt 6:26). God chose to use a colt as the way to dignify Jesus’ triumphal entry (Zech 9:9; Luke 19:30), and even divinely tamed the non-saddle-trained young equine for the honour. These and other biblical references serve to heighten our expectation of encountering God’s graces as we endeavour to rightly care for his creatures, in Jesus’ name.

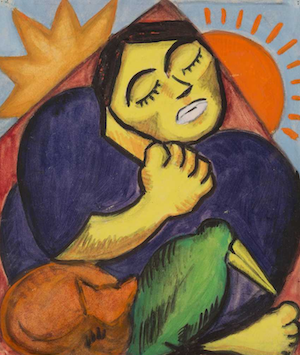

Edward Sellner’s lovely little book Celtic Saints and Animal Stories: A Spiritual Kinship (New York: Paulist Press, 2020), is a collection of reports of early Christian saints’ nurture of animals and how their lives were blessed in return. The genre of hagiography can at times read more like legend than history, but I tend to believe many of even the more supernatural accounts, for I have experienced some unexpected, marvellous connections with animals myself. A feral cat allowing me to rescue her. An injured dog who did not know me at all willingly accepting my invitation to climb into the passenger side of my car. A frightened frog in a hurricane seeking refuge in the palm of my hand. Pets who convey unconditional love, comforting companionship, and even deep-level heart-healing. I could go on. Each time, the presence of God as the source of life and hope and help was palpable and soul-nourishing.

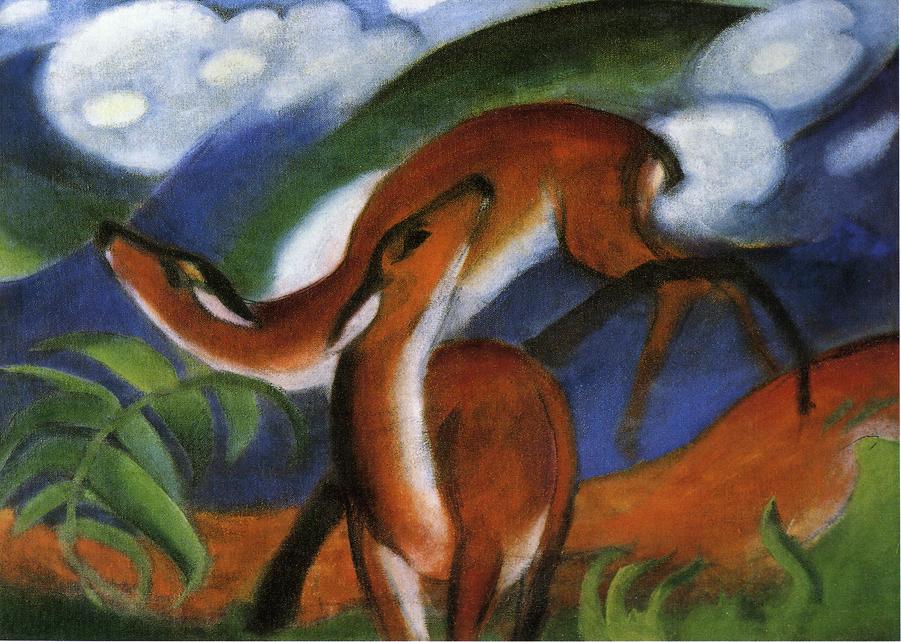

Sellner dedicates his book to two people and a dog. The people are the Linzeys of the Oxford Centre for Animal Ethics, of which I am also a Fellow. The dog is his beloved cocker spaniel “Red,” whom Sellner calls his “teacher and muse.” Recall how “nurturing” includes teaching and encouraging. As Sellner nurtured Red, so Red nurtured Sellner, and was therefore part of the process which ultimately led to me reading this book, and being nurtured by it as well. Some of my favourite quotes from his book are his affirmation that “both saints and animals are to be seen as soul friends and mediators of wisdom, capable of inspiring a deeper spirituality, a new ethic of holiness for our own time” (24), and from St Columban, “If you wish to know the Creator, come to know his creatures” (25). The stories he recounts result in the reader being moved to greater compassion for animals and to greater admiration for the saints whose godliness included a lifestyle of learning from and caring for animals. Sellner includes the famous story of how St Patrick “was moved to kindness like a godly father” (31) when his charioteer’s horses were missing, causing the charioteer who considered them close friends to be in a tearful state. God used Patrick to illuminate the way in the midst of the dark night to where the horses were, and the reunion was a great relief and noted as a miracle. An overall theme in this hagiography is how a maturing love for Christ will manifest in greater care for creatures, and how a greater love for creatures will nourish a more mature love for Christ. These stories are truly examples of how the godly rightly care for creatures (Prov 12:10).

Here are some organisations through which God can nurture you as you nurture his creation:

Get the latest issue in print or subscribe for the next three.