Otto Bam is a South African musician, writer, and student of literature. He is a member of KRUX, Stellenbosch (www.krux.africa) and holds a master’s degree in English Studies from Stellenbosch University.

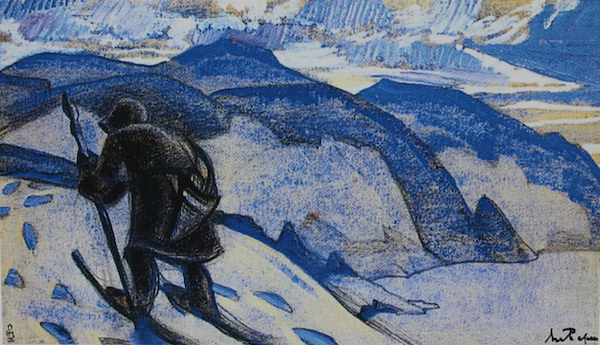

J. R. R. Tolkien said that “Fairy Land is full of wonder but not of information.” I am attempting to write about a great Fairy Story. My aim is to explain the effect the story might have on the reader. This is dangerous. It is dangerous to try to explain anything about Fairy Land because you run the risk of explaining it away. Tolkien called himself a mere wanderer in Fairy Land. I suppose we all are. And that seems to be just about the best thing to aim at being in Fairy Land.

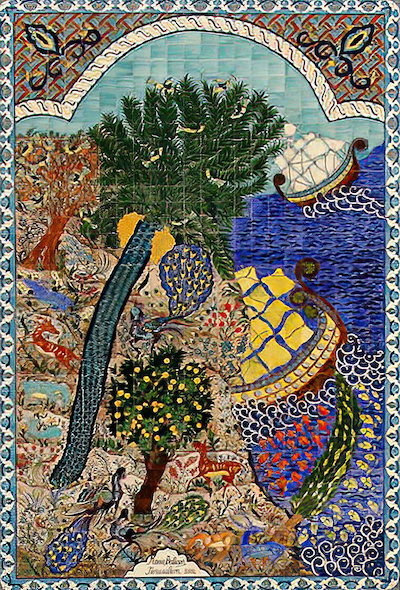

George MacDonald’s hero in Phantastes is the quintessential wanderer. His very name, Anodos, can be translated from Greek as “pathless.” The story begins with an inheritance – that is to say, it does not begin at all. It is without beginning, and its opening points to the ancient origins of every human story. Anodos had just turned 21 and had been handed a key to a secretary desk. He opens the cabinet, hoping to perhaps learn about “my father, whose personal history was unknown to me” (6). He finds, instead, a fairy who tells him that he is about to discover Fairy Land. Instead of finding the past of his father, he finds the path of his fathers. He enters into the wandering life of exile from Eden.

The morning after he had received the fairy’s oracle, Anodos wakes to the sound of the marble basin near his bed overflowing, forming a stream that runs into a forest. As the fairy had foretold, he has found the path into Fairy Land. But hardly has he found the path into Fairy Land, before he, “without any good reason, and with a vague feeling that I ought to have followed its course,” veers off it. He is pathless, bound to follow the way of Cain – the original wanderer.

References to Genesis are plentiful in Phantastes. Not least in a poem that appears at the beginning of Chapter 10:

From Eden’s bowers the full-fed rivers flow,

To guide the outcasts to the land of woe:

Our Earth one little toiling streamlet yields,

To guide the wanderers to the happy fields.

The first half of this poem echoes the exile from the garden. Genesis chapter 1 describes the four rivers that flowed out of Eden. Almost prefiguring the path out of the garden that the first pair were condemned to follow.

The second half of this poem, however, gestures towards the reemergence of these streams in the barrenness of the exilic life. To follow them is to move towards, and once again find, “the happy fields.” This presents the appropriate occasion for acknowledging the second meaning of Anodos’s name: “ascent.”

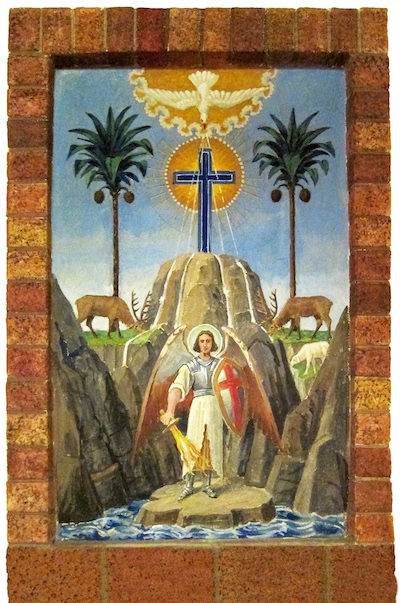

This second meaning of his name carries the notion of pilgrimage, of a journey directed at a particular destination. The association between ascent and glad rivers that spring up in the wilderness, as seen in MacDonald’s poem, features strongly in the prophecies of Isaiah and the psalms. But perhaps the clearest example is Psalm 84:

Blessed are those whose strength is in you,

in whose heart are the highways to Zion.

As they go through the Valley of Baca

they make it a place of springs;

the early rain also covers it with pools.

They go from strength to strength;

each one appears before God in Zion.

(Ps 84:5-7 ESV)

The dual meaning of the protagonist’s name, “pathless” and “ascent,” points to the sense that his journey is – despite his constant and almost obstinate propensity to leave what might be considered the “right”

path – somehow directed. Ascent recalls the journeys of the Israelites towards Zion to keep the great feasts.

Like Anodos’s name, Phantastes presents us with a world characterised by contrasting and intermingling experiences. Pathlessness and sovereign guidance. Sorrow and redeeming grace. Death and resurrection.

One of the most moving passages in Phantastes appears when the hero is in a state of utter exhaustion. He had entered a cottage which he had been warned to avoid and opened a door that he had been told not to open. A great shadow had rushed out from the abyss beyond and had become a fiend plaguing his every step. In this hopeless, helpless and pathless state, Anodos wanders into a desert region. Here he notices a spring “bursting from the heart of a sun-heated rock, flowing Southward” (64). The stream may be regarded as the first faint sign of a restored Eden. The stream grows into a river, and its banks are eventually lined with lush vegetation. Amid great sorrow he finds great comfort:

At length, in a nook of the river, gloomy with the weight of overhanging foliage, and still and deep as a soul in which the torrent eddies of pain have hollowed a great gulf, and then, subsiding in violence, have left it full of a motionless, fathomless sorrow – I saw a little boat lying. (66)

Such moments of eucatastrophe, to borrow Tolkien’s term, though occurring in a land of fantasy, offer a strangely real vision of the world. Indeed, this is the great power of Phantastes. Not that it offers an escape from reality, but rather, acting as a mirror, it reflects our own, perhaps stranger, world back to us. It calls forth the imagination in those who have forbidden the imagination to inform their conception of the real. It reawakens what G. K. Chesterton described as “the most wild and soaring sort of imagination, the imagination that can see what is there.”

At the end of the Phantastes, Anodos returns from Fairy Land. Back in the familiar land of his father’s estate, he remembers an old woman “who knew something too good to be told” (184). Perhaps that is the gift offered by George MacDonald’s Phantastes – not merely the comforting communion of a character who shares the acute grief and disorientation of life, but also an inexpressible sense of having met someone who knows of something inexpressible. Like the old woman, Phantastes seems to know about an unimagined good, and allows us to feel on our faces, to borrow C. S. Lewis’s metaphor, a cool breeze from a land we have never yet seen.

I have said that the best thing to be in Fairy Land is a wanderer. It may be more accurate to say that the best thing to be in Fairy Land is in it. If we are willing to look into the mirror that is Phantastes, we will see that we are.

Get the latest issue in print or subscribe for the next three.