Cas Monaco, PhD, serves as VP of Missiology and Gospel Engagement for FamilyLife and lives with her husband Bob in Durham, North Carolina. She is an Associate Fellow of the KLC.

Lesslie Newbigin posed this question in his 1984 Warfield Lectures:

“What would be involved in a genuinely missionary encounter between the gospel and this whole way of perceiving, thinking, and living that we call ‘modern Western culture?'” (Lesslie Newbigin, Foolishness to the Greeks: The Gospel and Western Culture [Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1986], 1)

This critically important question surfaced for Newbigin after he returned home to England from the foreign mission field, only to discover an entirely new mission field in his own backyard. He observes that missionaries and missiologists had made significant contributions pertaining to contextualization and cross-cultural missions overseas. But they had neglected the need for contextualization within their own powerful, persuasive, and resistant, modern Western culture. He then issued a clarion call to missiologists that resounds still today.

“There is no higher priority for the research work of missiologists than to ask the question of what would be involved in a genuinely missionary encounter between the gospel and this modern Western culture.” (Foolishness, 3)

I feel compelled to help answer this call. My discovery through research, interactions with Scripture, and conversations with people today is that the doctrine of creation cannot be underestimated when it comes to meaningful gospel conversations. This is especially the case in our current secular age.

Canadian philosopher Charles Taylor characterizes the twenty-first century context as being secularized. It is exclusively humanist and is devoid of sacred authority. Taylor describes this era as one in which people find belief in God not only implausible but even unimaginable. He insists that being secularized is not the absence but rather the presence of belief. He posits that secularization exists within an entirely natural and humanistic frame and displaces theistic belief from the default position. This creates a new set of faith assumptions or beliefs about history, identity, morality, society and rationality. In his My Life among the Deathworks: Illustrations of the Aesthetics of Authority ([Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press, 2006], 13), Philip Rieff warns, “The notion of a culture that persists independent of all sacred orders is unprecedented in human history.” He alerts his readers to an inevitable set of problems that arises due to an empty and meaningless sacred centre.

Today most people view the world based entirely on what they can explain or experience without any reference to God – a truly secular understanding. This denial of the supernatural has led to what Charles Taylor describes as exclusive humanism, a radical new option in the marketplace of beliefs that accepts no final goal beyond our present existence. He describes this marketplace of beliefs as a “super-nova – a kind of galloping pluralism on a spiritual plane.” (In A Secular Age [Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press/Harvard University Press, 2007], 300). This view treats Christianity as being just one option among an explosion of other choices.

Taylor’s assertions continue to be validated by current research studies in Western societies. For example, Cru’s 2016 US Research Study, Understanding Faith and Purpose in the City, reveals that more than half of the four hundred people surveyed claimed no religious affiliation, and describe Christianity as offensive, inauthentic, irrelevant or unsafe.(1) Stephen Bullivant, in his study, “European Young Adults and Religion,”(2) discovered that in the Czech Republic, ninety-one percent of young adults categorized themselves as religiously unaffiliated, and seventy percent have never gone to church. In the UK, France, Belgium, Spain and the Netherlands over fifty percent of those surveyed said they never go to church and never pray. In this study, Bullivant notes: “Cultural religious identities just aren’t being passed on from parents to children. It just washes straight off them.” Christianity is just one option of belief among a myriad of others and is increasingly among the least appealing.

If we are committed to fostering a genuine missionary encounter in our day between the gospel and Western culture, then we must cultivate an increasing awareness of this pervasive secularization. We must counter and engage the effects of today’s galloping pluralism that is rife with options void of substance and meaning. In his lecture, “Seven Lies of the Global Youth Culture” (Steiger Online Intensive Training, Worldwide Online, November 18, 2022), Luke Greenwood identifies these cultural fables that betray the emptiness in a post-Christian Western culture. I contend that at least five connect back to the doctrine of creation.

The first lie is embedded in our secularized culture that holds, “We can only be sure of what we see.” This fable is predicated on the notion that truth is relative to each person leaving our deepest questions forever unanswered: Why am I here? Who Am I? Is there a God? Second, since there are no answers for our deepest questions, then, this lie suggests that logically speaking, “We must be here by accident.” In other words, since there’s no grand purpose for this life, then it doesn’t really matter who I am or what I do. The third lie conveys the personal freedom that, “We can be whoever we want to be,” but in truth, this quest seldom proves to be true.

Fourth, there is the lie that, “Everything is going to be OK.” This ignores our shared global reality regarding the staggering rise in mental health issues and suicide. To believe this lie leads to an endless search for something, anything, to assuage our fears and anxiety. Finally, there is the lie that, “Love is just a passing feeling.” This suggests that relationships are fluid and change all the time, leaving no possibility of true companionship. All of these cultural lies provide us with significant opportunities to engage in meaningful gospel conversations by drawing from the doctrine of creation.

A recent and helpful publication by Bruce Riley Ashford and Craig G. Bartholomew, The Doctrine of Creation: A Constructive Kuyperian Approach, (Downers Grove, ILL: IVP Academic, 2020), presents a substantive look at the doctrine of creation from a trinitarian, Christocentric point of view. It is comprehensive, leaves no area of life or reason untouched, and opens a door for meaningful gospel conversations in a secularized era. Here I note five important aspects of this doctrine.

First, the doctrine of creation establishes a worldview that includes all that is seen and unseen, and, when rightly understood, orients and reorients every aspect of life. The Scriptures that begin with God creating the world ex nihilo continue across the canon to portray God’s power over and action within creation. By faith we affirm that God transcends the frame of a merely human existence within the natural world.

Second, the doctrine of creation is an article of faith, historically embedded, and marked by the Apostle’s Creed and the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed. It is important to note that in relation to God that our rational logic is limited, and that faith can and must swim deeply into the mystery of God as revealed in Scripture (23).

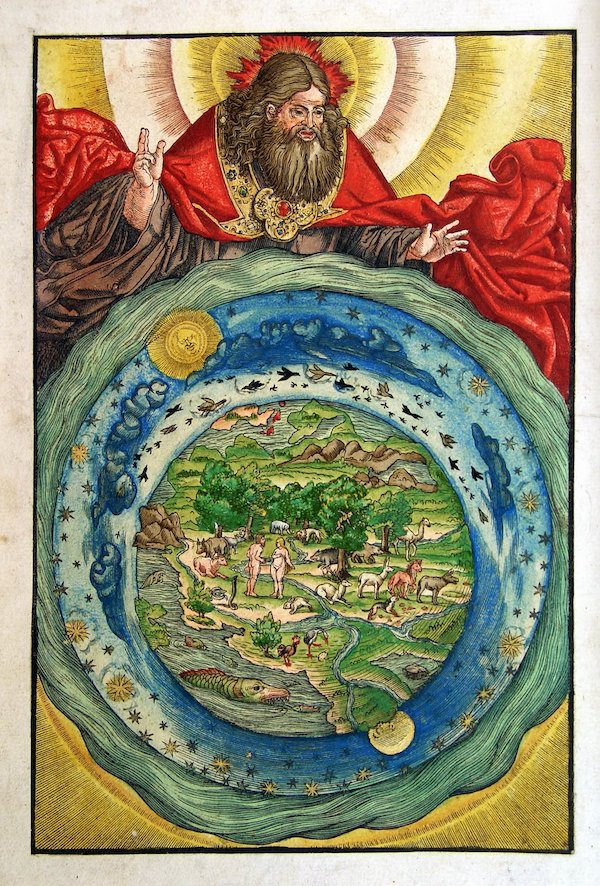

Third, the doctrine of creation is the opening act in the divine drama of Scripture. Here God furnishes the earth, creates multiple and diverse inhabitants and places in both the earthly and heavenly realms. God’s creativity is displayed in the beauty and diversity of creation in God’s relationship and partnership with Adam and Eve.

Fourth, the doctrine of creation, contrary to the claims of unsupervised evolution theory, affirms that humankind is uniquely created, specifically gendered, and called to cultivate and fill the earth. Humans are created for relationships with God, with self, with others and embody the capacity to love and to be loved. Yet, what God declared as good both structurally and directionally, is corrupted by Adam and Eve’s rebellion against God and marks the expulsion of humankind from the garden. Sin, autonomy from God’s authority, corrupts and misdirects God’s good purposes.

Fifth, the doctrine of creation affirms the good news that this divine drama climaxes in God’s greatest demonstration of love, the incarnation of Jesus. This inbreaking of God culminated in his suffering and death showing us in human and tangible ways that he loves us by sacrificing himself for our sake. Jesus Christ, through his resurrection, is the firstborn of the new creation and embodies a living hope presently and for the life to come.

There is no doubt that the effects of the galloping pluralism in secular Western culture are everywhere and are deeply troubling. It is only by being willing to stop, to listen, and to understand that we will be invited to talk with others about the God we love. In today’s secularized context, the doctrine of creation serves as a critical launching pad for meaningful conversations.

When we read the Bible, we encounter the creator across the storyline time and again. Creation is not only a phenomenon that took place in the past tense at the beginning of time. In astounding ways, it continues to unfold across the entire canon of Scripture and is magnificently realized in the incarnation, crucifixion, resurrection and ascension of Jesus Christ (Col 1:15–22). Notably, Ashford and Bartholomew call attention to the continuity between creation and providence to demonstrate what is called the creatio continua. “God is lovingly sovereign over his creation and remains deeply involved in it” (277). This realization affects our view of contextualization and enables us to see the opportunities for meaningful gospel conversations that issue from the doctrine of creation. In fact, introducing secularized people to their creator who loves them is a step toward addressing life’s most poignant questions. A friend of mine who interacts with high school students around the gospel often starts with Genesis 1–3. He notes that the creation story is often the first alternative to Darwinism and evolutionary theory these students have ever heard. They discover that their lives actually matter.

I often find myself in conversations with friends about marriage and family. Sometimes we discuss the desire to have children, the struggle and fear of infertility or, conversely, the option of abortion. These are deeply emotional topics to discuss, especially with people who have been conditioned to live within the immanent frame. Here, I share the gospel beginning with Psalm 139 and introduce them, often for the first time, to God their creator who creates humankind and gives life and breath to every living thing. This means that their lives matter!

To understand the implications of the doctrine of creation in a secularized context, we must accept the fact that most of the people we converse with today know little or nothing about Jesus let alone God the creator. Most don’t believe in God and some never even think about God at all. So, the doctrine of creation proves to be a good place for us to begin to build a foundation for understanding the living God as we seek to faithfully recontextualize the gospel for a secular age.

Get the latest issue in print or subscribe for the next three.