Peter Fedynsky’s 2013 translation of The Kobzar is the first ever complete rendition of Shevchenko’s poetry in English (available on Amazon and Goodreads). Fedynsky was an international broadcaster with the Ukrainian and English Services of the Voice of America from 1978 through 2013.

More than 1200 monuments to Taras Shevchenko across Ukraine and at least 125 around the world attest to the poet’s continued relevance and popularity among Ukrainians. A translator’s challenge is to convey the beauty and significance of Shevchenko’s poetry into another language, though none shares identical linguistic and cultural codes. The poet’s rendition of the widely recognized psalm below is a simple example.

Excerpt from “Imitation of Psalm 11”:

“… For my shackled people,

For the poor, the destitute … I’ll exalt

Those mute and lowly slaves!

And beside them as a sentry

I will place the word.

And your thoughts and speech will wither

Just like trampled grass.”

Your lofty words, O Lord,

Resemble silver, forged, struck,

And seven times refined by fire in a furnace.

Spread Your holy words

All throughout the world.

The excerpt above highlights his belief in the power of words and also the challenges of translation apart from language. A subtle nuance of this verse is the psalm number, which differs between faiths, beginning with the 9th. It would be Psalm 12 in the King James Bible. It’s a minor detail but a myriad of them creates the gulf between languages and cultures.

Context is needed to fully appreciate Shevchenko: who, to a non-Ukrainian, was Kotliarevsky? What is a third rooster? A kobzar? Chumák? The Hetmanate? The rivers Alta, Trubailo and others? The fact that they are little known internationally can be partly attributed to Russian censors, who intentionally hid Ukraine from the world for centuries. My translation provides numerous footnotes to help understand the poems.

Shevchenko was born a serf in 1814 on the right bank of Ukraine’s Dnipro River. His father was a so-called chumak who transported goods by oxcart. Today, he might have been a lorry driver. His hardworking mother was responsible for nine children and field work for the serf owner. She died when Taras was nine. Before his death two years later, the father took his son on a few trips, which gave the young Shevchenko a dawning awareness of life beyond village confines. The orphan’s owner, Pavel Engelhardt, took him into his manor as a servant. Engelhardt, the illegitimate son of Russian General Vasily Engelhardt, inherited his father’s serfs. When Shevchenko was 15, Pavel Engelhardt moved to Vilno, today’s Vilnius, and brought Taras along. A local Polish girlfriend made him better realize his bondage; she was free to do as she pleased, he was someone’s commodity. The future poet’s 16-month stay in Vilno also coincided with the Polish Uprising of 1830–31, which prompted Engelhardt to move again, this time to St Petersburg, but not before Shevchenko witnessed part of the armed Polish struggle for independence. Shevchenko biographer Pavlo Zaitsev suggests that the national implications of the rebellion would not have escaped his attention. In other words, if Poles could fight for their freedom, why not Ukrainians?

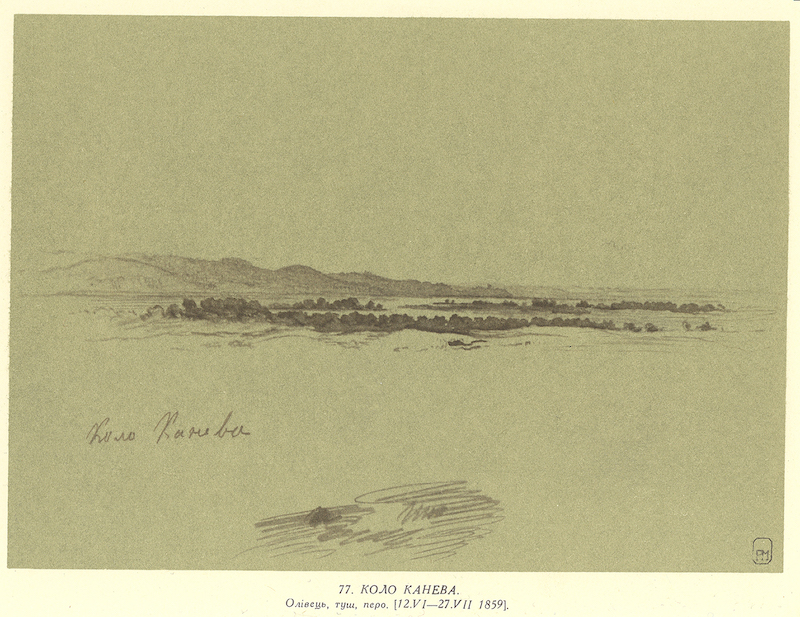

In the imperial capital, Shevchenko’s artistic abilities drew the attention of several Ukrainian and Russian intellectuals who organized an art auction to raise funds to purchase his freedom in 1838. Fast forward through his fine education in the St Petersburg Academy of Arts to the first two of his three trips to Ukraine that covered astounding distances. He crisscrossed the Ukrainian heartland on an axis roughly 525 miles from the northwest to the southeast and 425 miles northeast to southwest. His first trip as a 29-year-old yielded a series of etchings featuring quotidian slices of Ukrainian life. He also began a series of poems known as The Three Years, which he completed on his second trip from 1845 to 1847 as an artist on an imperial archaeological expedition. Shevchenko, already a well-known poet, was a welcome guest in wealthy manors and peasant huts alike. His dawning boyhood awareness developed into intimate familiarity with Ukraine and Ukrainians. Not only did he produce a painted record of what he saw, he also poeticized Ukrainian folklore, customs, songs and aspirations of serfs. In addition, he studied dozens of ancient burial mounds. The word mound appears more than 100 times in his poetry collection, The Kobzar (The Minstrel). A mound connotes not only the place where ancestors rest, but is also a symbol of Ukrainian historical and cultural continuity as each succeeding generation is buried above forebears.

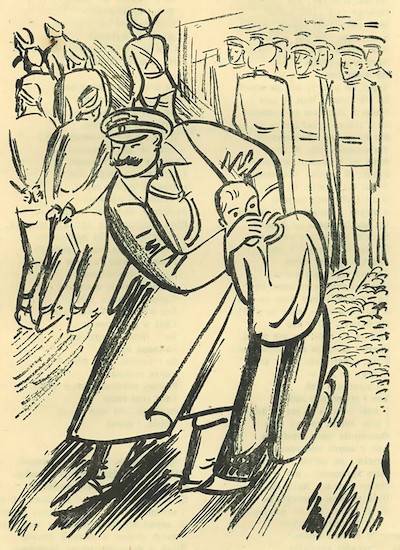

A poem titled “Plundered Mound” has remained relevant since he wrote it in 1843. Ninety years later, it was one of many verses in a new Kobzar edition illustrated by artist Vasyl Sedliar. He was executed for substituting Soviet goons for the poet’s czarist overlords. And today, as Russian troops target Ukrainian civilians, blow up infrastructure, including dams, and force millions to seek shelter abroad, Shevchenko’s “Plundered Mound” still resonates.

… My sons do foreign work

In distant foreign lands.

The Dnipro, my dear brother,

Running dry, abandons me,

And the mounds so dear to me

Are plundered by the Muscovite …

Let him plunder, dig them up

What he seeks is not his own,

And meanwhile, let the turncoats grow

To help the Muscovite keep house,

And to strip the tattered shirt

From off their mother’s back.

Help them, brutes,

To rack your mother.

The plundered mound

Is dug in quarters.

What is it they were looking for?

What did the old folks hide? –

Ah, if only,

If only they would find what’s hidden,

Children would not weep, nor would mother worry.

Another poem from The Three Years series is “The Testament,” Shevchenko’s clarion call for Ukrainian freedom:

When I die, then bury me

Atop a mound

Amid the steppe’s expanse

In my beloved Ukraine,

So I may see

The great broad fields,

The Dnipro and the cliffs,

So I may hear the river roar.

When it carries hostile blood

From Ukraine into the azure sea …

I’ll then forsake

The fields and hills –

I’ll leave it all,

Taking wing to pray

To God Himself … till

Then I know not God.

Bury me, rise up,

And break your chains

Then sprinkle liberty

With hostile wicked blood.

And in a great new family,

A family of the free,

Forget not to remember me

With a kind and gentle word.

The last line of “The Testament,” Незлим тихим словом, is one of the poet’s most difficult to convey in English for several reasons, among them the untranslatable word “незлим.” The term joins the words “not” and “bad.” Writing both together is more gracious. If English had this word, it would be spelled “notbad” and would be perceived in a subdued key. In its absence, the translator must choose between literal and smooth. The mere “not bad” would be too brusque; a compromise is “kind.”

Another reason involves the adjective тихим, which means quiet. But using it would create a distracting alliteration: kind and quiet. The word “gentle,” instead, introduces a shade of meaning not as precise as quiet, but it is more soothing than the guttural “k” alliteration. The next challenge is the ablative case. Ukrainian shares it with Latin but not English, which relies on prepositions or word order to convey similar content. In Ukrainian, the ablative makes the preposition redundant and allows “with” to be implied in any word. This makes for terser writing.

English has a rich vocabulary to refine meaning but few diminutives. In Ukrainian, there are frequently several, not only for nouns, but also for adjectives and adverbs. For instance, it is impossible to convey in English the verve of Shevchenko’s penultimate word in The Kobzar – veselenko. For lack of a better one, I chose cheerfully. If that’s all the poet wanted to say, he would have selected the root word veselo, though he could have written veselesenko, but that would have been overkill. Veselenko best conveys the sans souci of a man facing death and writing his last poem to express his love of life and wish for more. Veselenko qualifies the word sing, i.e., he and his muse will cheerfully sing in the afterlife. Life is good, it will go on, not just cheerfully, but … well … veselenko. It can’t be translated.

Shevchenko brims with alliteration and assonance that harmonize an already melodious language. For example, in his poem “The Slave” he writes: “Знову (again) забіліла (whitened) зима (winter) біла (white).” Shevchenko’s string of “z” sounds can be partly substituted in English with “w” – White winter whitened all, again. The poet carries the alliteration to the next line. “За зимою (after winter) зазеленіла (turned green) весна Божа (God’s spring).” Here, this translator’s luck ran out. I rendered the second line as “After winter came God’s spring and greenery.” The meaning is preserved but not the lyricism.

Shevchenko also relies heavily on syntactical inversion, which is endlessly flexible in Ukrainian. For example, the inverted word order for the phrase Мої там сльози пролились from the poem “If You Gentlemen But Knew” sounds loftier than what one might ordinarily say. There are 24 combinations of those words in Ukrainian, all of which make sense. Not so in English. The original word order in English translation: “My there tears shed,” is gibberish. In addition, Shevchenko often uses the passive voice to underscore his emphasis on fate, which victimized millions of Ukrainians through their accident of birth into serfdom. English tends toward the active voice.

Shevchenko used complicated and shifting metres, which I did not attempt to duplicate. To match his rhythms and rhymes would be a Herculean task, perhaps more difficult than translating the King James Bible, which took seven years and 47 scholars and theologians to complete. I settled for anapest throughout to convey what Shevchenko said, not how he said it. Some of his words are neologisms from Church Slavonic, whose flavour is impossible to convey without resorting to Middle English vocabulary, which has lost currency. Ukrainian Orthodox and Catholic Christians were attuned to the ancient language, which they heard in Eastern Rite church services.

As a foundational text, Shevchenko’s Kobzar has played an important role in galvanizing the Ukrainian identity and in the development of Ukrainian literature and language. The book’s compelling poetry and simple but soaring eloquence are considered timeless meditations about beauty and brutality, the meek and the mighty, fame and fortune, love and lust, religion and morality, but above all about hope and justice.

Shevchenko belongs in the company of such global giants of world literature as Byron, Goethe, Mickiewicz and Pushkin. But his native Ukrainian language, culture, history and geography had long been either denigrated as inferior or even prohibited by a hostile neighbour who used and continues to use brutal force in an attempt to subjugate Ukraine, her wealth and her people. Shevchenko did not countenance it, nor do Ukrainians today as they continue the struggle for liberty embodied by their revered national poet long after his death in 1861.