John DelHousaye is professor of Bible at Arizona Christian University and a theologian in residence with Surge Network and the Spiritual Formation Society of Arizona. He is an Associate Fellow of the KLC.

Accused of “making himself equal with God,” Jesus Christ responds with an apologia that ends ironically with his accusers on trial for their disbelief and cheap products:

So Jesus answered and was saying to them: “Amen, amen, I say to you: the son is unable to make anything for himself except what he sees the Father making. For whatever he should make, the son also likewise makes these things. For the Father loves (as a friend) the son and shows him all things that he is making [Gen 1:1; Prov 8:27–30]. And greater works (of creation) than these he will show him, that you all will wonder. For as the Father raises those who are dead and makes them alive, likewise the son also makes alive whomever he desires [1 Sam 2:6]. For the Father does not judge anyone but has given all judgement to the son, that all might honour him as they might honour the Father. The one who does not honour the son does not honour the Father who sent him. […] Amen, amen I say to you: the one who hears my word (logos) and believes in the one who sent me has eternal life and does not come into judgement but has crossed over from death into life. […] Amen, amen I say to you: the hour is coming and now is when those who are dead will hear the voice of the son of God, and the ones who hear will live [Dan 12:2]. For as the Father has life in himself, in the same way he also gave life to the son to have life in himself. And he gave to him authority to practise judgement because he is the son of man [Dan 7:13–14]. Do not be astonished by this. For an hour is coming in which all who are in tombs will hear his voice and will come out – those who make good things to the resurrection of life, but those who make cheap things to the resurrection of judgement.” (John 5:19–29 my translation)

Jesus presents himself as a master apprentice: “whatever he should do, the son also likewise does … shows him all things.” In context, we learn that God has been working ceaselessly to repair creation (17). The Father’s craft, which is beautiful, useful and “good,” has captured the Son’s attention and become his own practice. Twice, Jesus stops speaking, watches, listens and responds: “Amen, amen.”

A son learning a trade from a father is a very familiar path of apprenticeship. The Synoptic Gospels present Jesus as a “craftsman” (tektōn) – not necessarily a carpenter since woodworking was fairly scarce – from Nazareth like his earthly father (Matt 13:55; Mark 6:3). As a youth, he probably assisted Joseph with repairing and enlarging the nearby city of Sepphoris that had been destroyed by the Romans shortly after his birth but which, by the late first century, the Jewish historian Josephus describes as the “ornament of all Galilee” (Antiquities 18.2.1). John modulates the Synoptic tradition into a cosmic apprenticeship: responding to his heavenly Father’s direction, Jesus is now repairing and enlarging all creation in his own person, offering his flesh as temple and groom. Jesus says, “Destroy this temple,” referring to his own body that will be torn apart by the Romans, “and in three days I will raise it up” (2:19, 21). This resurrected flesh will also become a home for his bride, the church, so that we might abide in him and that he, the Father and Holy Spirit live and work in us (John 14–15).

The master apprentice grounds this ambitious defence on Ancient Israelite Scripture, a shared, revelatory authority between defendant and accusers, presenting himself as the antitype (or fulfilment) of Wisdom, Messiah and Daniel’s “son of man.” Often obscured in English biblical translations, Jesus employs the Septuagint’s opening verb – “In the beginning God made (poieō) the heaven and the earth” – to describe God’s craft, who, like a potter, moulds Adam’s body with clay, imbuing it with life (Gen 1:1; 2:7). Proverbs goes on to make Wisdom a participant in the creation story:

When he [Yahweh] established the heavens, I was there; when he drew a circle on the face of the deep … [Gen 1:1, 2] when he marked out the foundations of the earth, then I [Wisdom] was beside him, like a master workman, and I was daily his delight, rejoicing before him always. (8:27–30 ESV)

A “master workman” or “artist” (amon), Wisdom joyfully implements Yahweh’s creation plan, collaborating as a friend. Jesus then alludes to the first explicit reference to the Messiah (masiach) in Scripture, which unites resurrection after Adam and Eve’s fall with his exaltation:

Yahweh kills and brings to life; he brings down to Sheol and raises up … he will give strength to his King and exalt the horn of his Messiah. (1 Sam 2:6, 10 my translation)

Finally, Jesus employs gezerah sheva – an exegetical rule attributed to the contemporary rabbi Hillel that allows different passages to be linked by a common word or theme (see Tosefta Sanhedrin 7:11) – within Daniel, so that “son of man” has authority to judge after Yahweh brings the dead to life from Sheol:

With the clouds of heaven there came one like a son of man, and he came to the Ancient of Days and was presented before him. And to him was given dominion and glory and a kingdom, that all peoples, nations, and languages should serve him … And many of those who sleep in the dust of the earth shall awake, some to everlasting life, and some to shame and everlasting contempt. And those who are wise shall shine like the brightness of the sky above. (Dan 7:13–14; 12:2–3 ESV)

“Dust of the earth” brings us full circle: God created Adam from “dust” (Gen 2:7); he and his descendants would be resurrected from the same material. And by these three types or shadows, Jesus presents himself not only co-participating in creation and resurrection but also determining their course by his exaltation and judgement.

The accused, then, turns the tables on his accusers, promising to judge them at the resurrection for the quality of their craft – as either “good” (agathos) or “cheap” (phaulos). Here, and in an earlier occurrence, agathos also means valuable, presuming the utilitarian beauty of craft: Nathanael asks, “What good thing (agathos) can come from Nazareth?” (1:46), as if the small village had little to offer. It may already have been the case – at least it was so in medieval Europe – that “all” apprentices at the end of their initial training were required to submit a masterpiece to the guild for recognition. Something like that will take place at the general resurrection of the dead, as the apostle Paul describes:

Now if anyone builds on the foundation [Christ] with gold, silver, precious stones, wood, hay, straw, the work of each will become clear because the Day [of the Lord Jesus] will make it clear because it is revealed in fire. And the fire will test the quality of each (person’s) work. If anyone’s work remains, which he built, he will receive a reward. If the work of anyone is incinerated, he will suffer loss. (1 Cor 3:12–15a)

While Jesus apprentices the Creator Father, his accusers follow theirs: “You are from your father, the devil” (John 8:44).

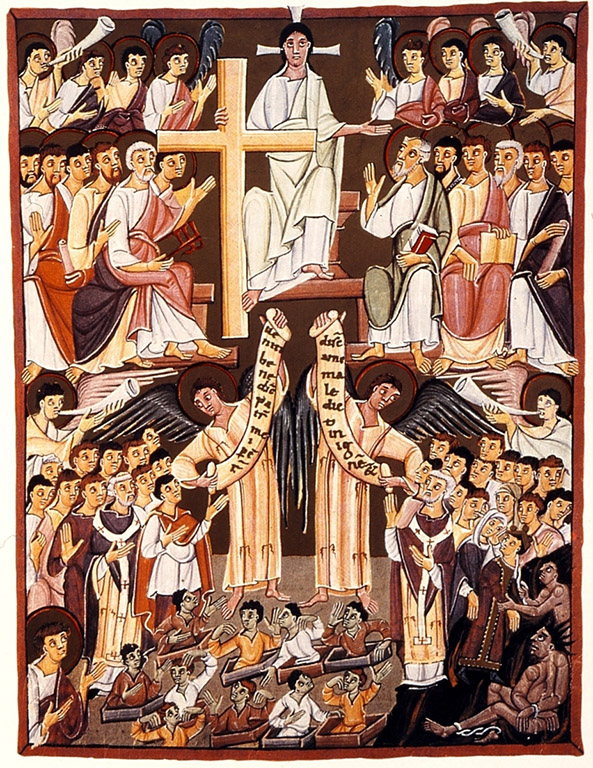

Breaking the fourth wall (metalepsis), as John often does, the passage terminates with a summons for readers to recognize their own apprenticeship and father because everyone’s work will be evaluated: “all who are in tombs will hear his voice and will come out.” But what Jesus invites is not the fallen expression of apprenticeship, a kind of slavery in which apprentices (“interns”) are exploited for free labour, but family, friendship and “wonder.” Much has been written on salvation as adoption into the Trinity and friendship with God. Perhaps less on the wonder of craft.

A certain Rudolph Elie wrote this for the Boston Herald in 1954:

For the last half hour, I have been standing, mouth ajar, down on Arch Street watching them lay bricks in the St. Anthony Shrine now “abuilding,” and I have come to the conclusion that laying bricks is a fine and noble and fascinating art.

Every skill has a scale of perfection, so that even proficient mastery invites wonder from the novice looking for beauty and order. Apprenticeship cannot be separated from the community that requires excellence in each skill for its well-being. Kingdoms can survive for a time without a king but not without trades whose masters have no need to justify their existence, though, like God, often go unappreciated. Why did the Bostonian feel the need to write the obvious?

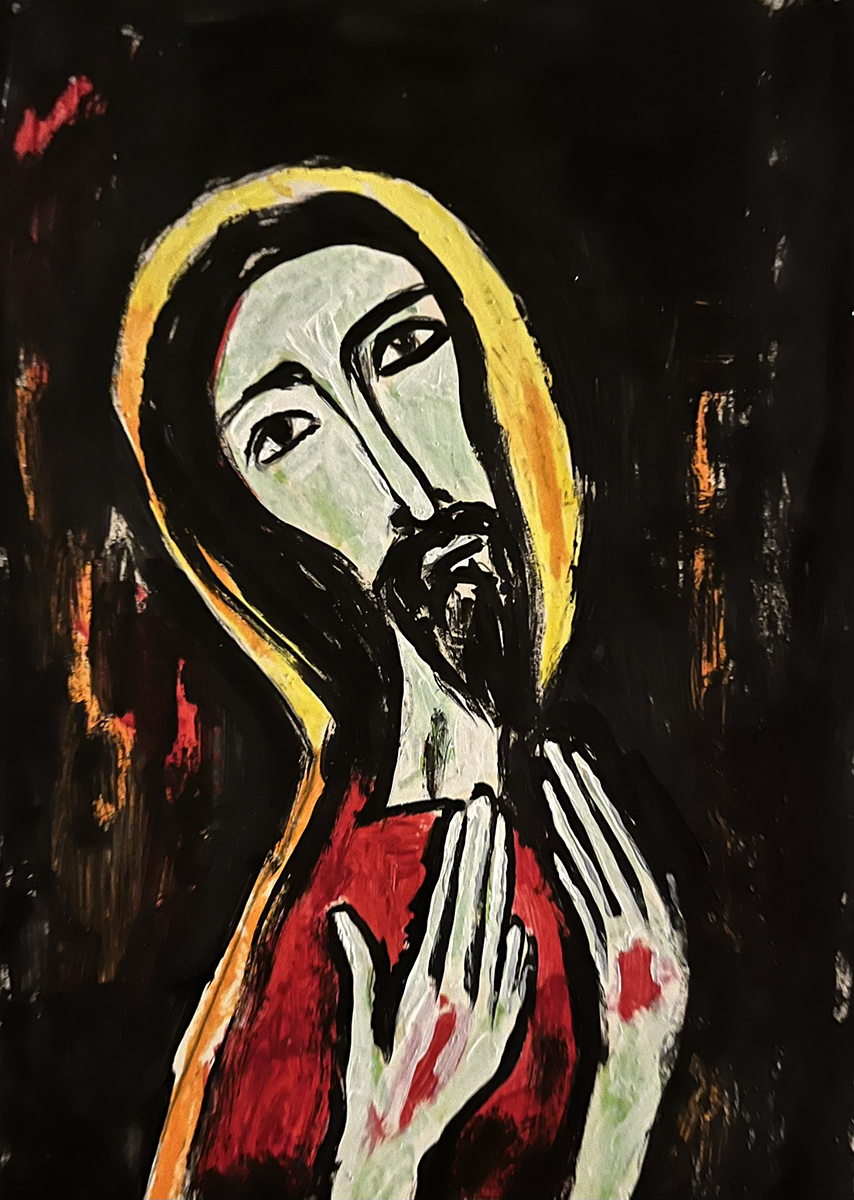

We too, like children standing “mouth ajar,” may wonder our way again into the kingdom of God. Their self-perception is smaller than adults’, so that the greatness of any craft may be seen. Little ones are more easily yet rightly astonished by the everyday work of the towering grownups around them. For many, our adult work began this way. (I wonder if a youthful Jesus beheld Joseph’s craft – cutting away, shaping, forming – and was drawn.) I teach the Bible for a living because I grew up watching my father (b. 1949) preach it well. I paint because Ray Swanson (1937–2004), celebrated for his honouring depiction of Native American children, invited me to his studio where he had set up two canvases before a flower in a cup. I watched his brush move with effortless intentionality like my father’s tongue; my shaky, undisciplined hand followed. At the end, there was clearly a gap in the scale of perfection between the two works, but I was hooked forever.

Wonder (thambos) also seized Peter and his partners as they beheld Jesus modulate their earthly livelihood with a miraculous catch (Luke 5:1–11; see also 4:36).

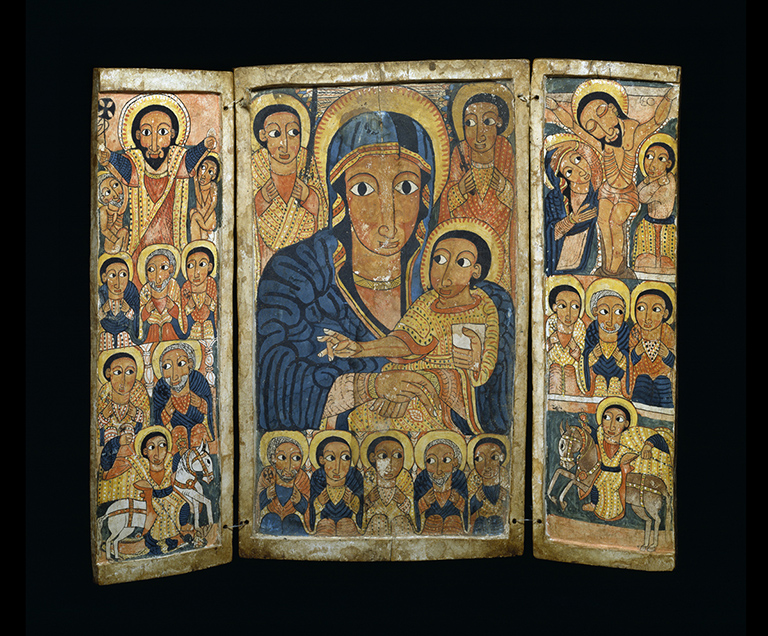

Adoption into God’s family means, at the age of maturity, taking on the trade. The beauty and goodness of new creation, like St Anthony’s Shrine, will be our humbly collective yet individually perfected labour: “We who cut mere stones must always be envisioning cathedrals” was a medieval quarry worker’s creed. I am not at all convinced that we take our bricklaying or noodle-making skills or our signed artworks or publications into eternity, but we will all behold New Jerusalem as our city. (Cheap nick-nacks are for tourists, and there will be no more tourists.)

Nevertheless, we must not push spiritual children to grow up too quickly. There is time for milk, for play, and for celebrating their first freedom from the evil one. At the time of Christ, apprenticeship began with pre-practice observation. This is the most natural way for tiring of toys. We can trust the power of proximity, that “good things” will be on display in the body of Christ, the church; and, at the right time, if their faith is genuine, they too will be attracted to the craft, especially if the community is deeply rooted in the Gospels. As modelled by the Triune God – more on this below – apprenticeship is essentially communal. We mirror the Son to one another as the Son images the Father. We are apprentices to the Apprentice, our work echoing God’s. (Although the master’s name is often the only one remembered, most great works in human history are necessarily collaborative.) For today’s apprentice, as Jesus will reveal in the Upper Room Discourse, the most immediate master is the Holy Spirit in that we are all anointed with “wisdom and understanding” distributed among the members of Christ’s body:

The Advocate, the Holy Spirit, whom the Father will send in my name – he will teach you all things and bring to your remembrance everything that I said to you. (John 14:25 my translation; see Isa 11:2)

The Advocate mirrors the Son: both come from the Father, dwell with disciples and offer truth. The Spirit makes us participants in Jesus’ circle, allowing us always to have the Apprentice before the eyes of our heart but also the freedom to create new things in his name. In the restoration of our Jesus-centred imaginations, apprenticeship moves from distraction to wonder, from imitation to creativity. Perhaps, at some point, throughout the day we will stop arguing with the world, watch, listen and respond: “Amen, amen.”

Jesus reveals something of the trinitarian craft of resurrection, the healing and perfection of creation, by presenting the general resurrection of the dead as a co-participation between the Father and Son. With the Holy Spirit, they are acting inside and around one another, in perfect, joyful community, as any apprentices know who carry the master’s spirit with them in their work. They share the same agency and operation: opera trinitas ad extra sunt indivisa (“the works of the Trinity on the outside are indivisible”), so that all creation will be a unified work. The Father resurrects and judges in the Son, who still operates with personal agency inside the freedom of friendship, anticipating the doctrine of dyothelitism (“two wills”). The Son has a divine will and a human will that he surrenders to the leading and inspiration of the Spirit; a second will and a second nature, which makes our own union with God possible. He is the last Adam, as we are the last Eve; and we have become one flesh, so that we might also become Wisdom, the Creator’s “helper,” while still being formed as part of creation (Gen 2:18).

Today, whatever our craft is, whatever we do well that has been determined to be attractive, necessary and useful for the common good, as a reflection of God’s creative activity, it is inside the scale of perfection, which ought to hook us forever. The master apprentice is always capable, never satisfied, always attracting the next generation to discipleship. God has captured our attention in Jesus Christ whose crucified yet resurrected body perfects creation, and we cannot look away. We may not see our city, our collaborative masterpiece, until our own resurrection – “all who are in tombs will hear his voice and will come out” – but there is something of his transfigured flesh in every village, family, friend and garden. There is space in God’s creative presence for imperfection, for personal growth, for the joy of learning better (never best) practices, but also for the less appealing, tediously boring, labour-intensive, even tragic moments of apprenticeship that sometimes feel more like slavery that are nevertheless essential to the constrained, mysterious freedom of any master.