The book of Revelation has, since the Church’s earliest days, proved challenging for the people of God. Challenges include speculation over its authorship, its place in the biblical canon, and its usefulness for Christian living. In a more positive sense, it challenges Christ’s church to live faithfully during difficult times and in the face of opposition from the Enemy. Given the Christian belief that it is inspired by the Holy Spirit and therefore of apostolic origin and written for our instruction, how, then, are we to read it profitably? How can we hear it as the Word of God for the people of God? More particularly, for those of who serve in ecclesial contexts, how can we faithfully proclaim and preach it? Below I want to offer a few broad guidelines for preaching John’s Apocalypse, and then mention some key resources for the preachers in their study.

The book of Revelation has, since the Church’s earliest days, proved challenging for the people of God. Challenges include speculation over its authorship, its place in the biblical canon, and its usefulness for Christian living. In a more positive sense, it challenges Christ’s church to live faithfully during difficult times and in the face of opposition from the Enemy. Given the Christian belief that it is inspired by the Holy Spirit and therefore of apostolic origin and written for our instruction, how, then, are we to read it profitably? How can we hear it as the Word of God for the people of God? More particularly, for those of who serve in ecclesial contexts, how can we faithfully proclaim and preach it? Below I want to offer a few broad guidelines for preaching John’s Apocalypse, and then mention some key resources for the preachers in their study.

The first key feature of Revelation to remember while reading and preaching is that it is a New Testament letter. In fact, it serves in many ways as the culmination of the NT letters, with its emphasis on the universality of Christ’s church in the letters to the seven churches (Rev 2–3) and its connection to the other NT letters in the language and structure of chapter 1 and 22:6–21. As with other NT letters, this means that Revelation is written to a particular people at a particular time facing their own particular challenges, but is also meant both by the human author and the divine author to speak to Christ’s church throughout space and time.

As we read and preach Revelation, we should recall often the fact that it was written to Christian churches throughout the Roman Empire facing challenges related to local and imperial persecution, socially-pressured opportunities for sinful pleasure, and a growing number of false prophets attempting to subvert the claims of Christ’s lordship over all things. While Revelation speaks to us today, it does so first of all to those believers within the first century of the church’s post-apostolic life. Attempting to understand its relevance for today thus means first understanding its relevance for that initial audience.

A second key feature of Revelation is that it is an apocalypse. That is, it is intended to communicate to its audience the nature of the end of the current age and the beginning of the eschaton, and it does so through heavy use of figurative imagery. We cannot miss that John begins his letter by giving us a figural key in 1:20 – the stars are messengers, or angels, and the lampstands are churches. John is telling us clearly that the contents of his book are intended to be read figurally. That is, John, under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit, uses figurative images to communicate the truth about reality. And, while he explains only two at the beginning of the book, stars and lampstands are but the surface of the deep well of images that John uses.

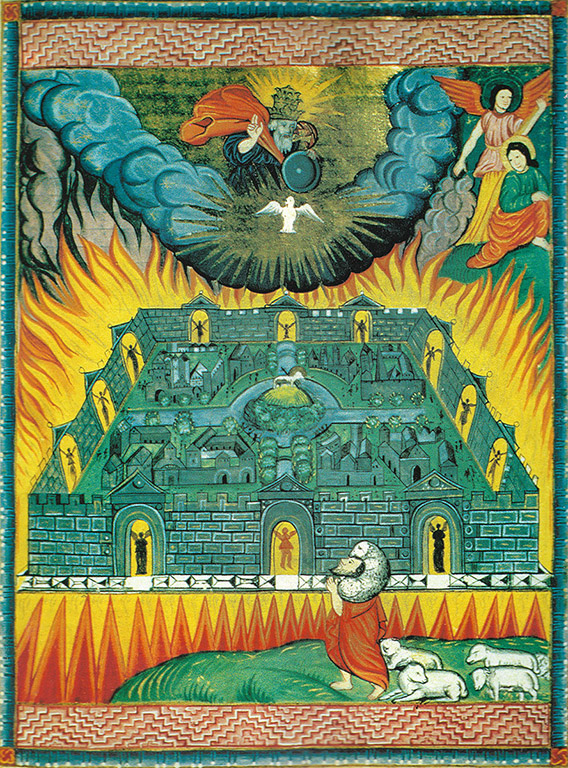

While attempting to understand and communicate the truths of Revelation’s imagery, we should also remember that the images John uses are taken primarily from the Old Testament. The Apocalypse is steeped in OT imagery (and textual allusions!), from the throne room scenes (chapters 4 and 5) to the woman in the wilderness (chapter 12) to the New Jerusalem (chapter 21) and everything else in between. We cannot understand what John is saying to his readers without understanding their socio-historical context because of its nature as a letter, and we also cannot understand what he is saying to his readers without understanding the Old Testament and the ways in which John deploys OT imagery throughout his book.

A third (but by no means final!) feature of Revelation we should remember as we read and preach it is that it has a particular structure. John is teaching us how to live faithfully in between the inauguration of the last days in Jesus’ life, death, resurrection and ascension, and their culmination in his impending return in glory. The contents of the vision, from 4:1–22:5, concern this eschatological period, between the already and the not yet. Thus, the book moves toward the finality of Christ’s return, final judgement and renewal of creation as described in chapters 20–22.

The remaining material describes the period between his first and second coming, and in two overlapping structures. First, there is a narrative thread that stretches throughout this middle section of 4–19, beginning with the throne room scenes in chapters 4 and 5; including the great war between the witnesses and the woman and their enemy, the Dragon and his servants, in chapters 11–14; and through the fall of Babylon and Armageddon in chapters 17–19. But there is also a cyclical structure overlaying this narrative, describing the ongoing but partial judgement of God poured out on sinners in the seven seals, trumpets, thunders and bowls. In each of these sequences, judgement is only partial, not final, highlighting both the righteousness and the mercy of God. He is righteous to judge sin and merciful to bring only partial tribulation and therefore to give time for those who remain to repent and believe. Each of these sequences, though, does end in final judgement (the sixth and seventh seal, and the seventh trumpet, thunder and bowl are each universal, cosmic, global judgements). It should go without saying, but we need to say explicitly – there can only be one final judgement. Therefore, these judgement sequences are intended to be describing the same period, the time between Christ’s first and second comings. As we preach through Revelation, it is important to keep in mind, then, that John is both pressing us toward final judgement and also doing so in a way that is not always sequential.

Ultimately, then, Revelation is a book about King Jesus. Through his life and work, he is King of kings and Lord of lords, ruling over all things. As believers, we can therefore face persecution, temptations to sinful pleasure, and false prophets with confidence that he is faithful and just to deliver us from our enemies. Resistance to our enemies thus comes by faith in the risen and victorious Christ, not by our might. Even when we are facing serious opposition all around us, Christ remains faithful to us and present with us by his Spirit and to the glory of the Father, and one day soon he will return to judge the living and the dead. This is the good news of Revelation, and the good news we can preach to our people.

In terms of resources, Matt Emerson’s Between the Cross and the Throne (Lexham, 2016) is a short introduction to the book. For an introduction to Revelation’s major theological themes and literary features, Richard Bauckham’s The Theology of the Book of Revelation (Cambridge, 1993) and Craig Koester’s Revelation and the End of All Things (Eerdmans, 2001) are both excellent. In terms of commentaries, G. K. Beale’s The Book of Revelation (Eerdmans, 1999) is very technical but incredibly insightful. Wilfrid Harrington’s Revelation (Liturgical Press, 1993) and Leon Morris’s Revelation (Eerdmans, 1987) are no less insightful but also a bit more accessible.