Otto Bam is the Arts Manager for the KLC, the ArtWay.eu editor and an Associate Fellow of the KLC.

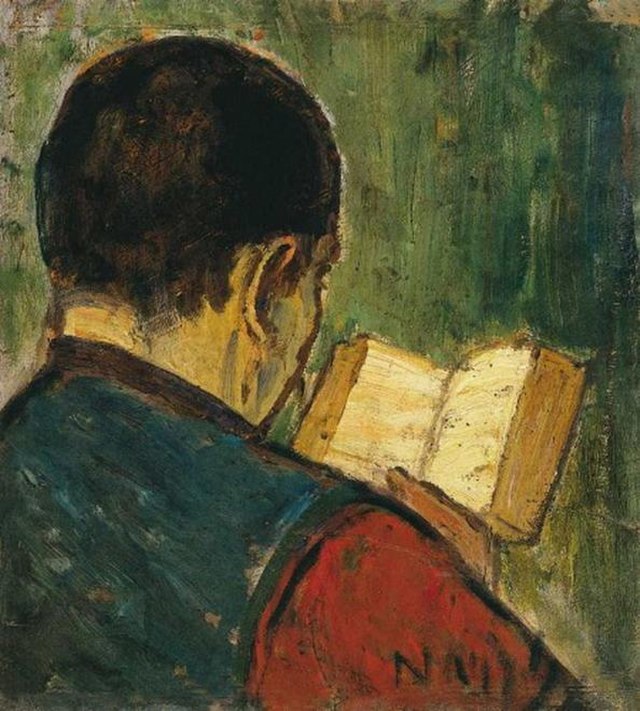

Much can be written and indeed has been written about writing as a craft. The writer is no mere medium – no mere conduit for inspiration. As a craftsman, the writer must practise and refine the craft regardless of the presence or absence of any muse. Most writing is not a matter of soaring inspiration, but of a steady sawing and sanding at the workbench. In the poem “Digging,” Seamus Heaney compares the writing of poetry to the backbreaking work of digging. The poet claims labour as his inheritance. Perhaps it can be granted, but what about that seemingly more elementary, leisurely, act of reading?

Laborious reading

As a child reading often did feel like labour to me. I did not excel at reading. I was reluctant to do it and slow when I did. I had trouble sitting still and my attention span was poor – no social media had been invented yet on which to pass the blame either. It was hard work! But my limitations had their advantages, for my slow reading, combined with a taste for symbolism, made me aware of the textures of language, and the stores of meaning in individual words and phrases. It helped me acquire a sensitivity towards how something was said as much for – initially perhaps, more than for – what was said.

As I began undergraduate studies in literature at the University of Stellenbosch in South Africa, I found it difficult to finish the novels I was given to read. I admit that many a Victorian novel only saw me for a few chapters. But what I did read I read with great attention and with an awareness of what the author was doing with language. I began to see the vistas that a mere word or sentence could open out onto when issuing from the pen of a great writer. My capacity for reading expanded as a graduate student, and my years of slow reading surprisingly began to be an advantage to me. It turned out that how something is said has everything to do with what is being said.

Slow, attentive reading runs counter to the cultural currents of our age, one that places great emphasis on speed and efficiency – on finishing things as quickly as possible. It holds an instrumental view of texts as it does of so many things. Language is seen as a sort of husk that contains the information we are after. Once the information has been extracted, we can discard the superfluous exterior. The poetry lessons I received at school might be summed up with the question, “What was the poet trying to say?” – a question common to many a well-meaning English teacher, asked before an exposition of the meaning in “normal” language. Once paraphrased in comfortable and clear everyday language, the ambiguities and uncertainties of poetry can safely be done away with.

But the secret of savouring poetry is not to get at the meaning behind the poem, but to get at the meaning in the poem. The poet is not trying to say some one thing. Rather, the poet knows how to say more than she herself knows she is saying. Poets are masters at wielding words in a way that lets loose the myriad meanings that live within the poems, lines and words themselves. They are not the masters of language, commanding sentences to deliver a pre-determined and completely known set of messages, but co-conspirators in language’s stubborn resistance to being tamed – and meaning’s refusal to be contained. Poets set language free to carry us across the expanse of the unknown and into the bosom of mystery for the sake of disclosure, however provisional such disclosure might be.

When reading is not a mere matter of gaining information, when literature is encountered in all its physicality – for the texture and depth of its words – it has the potential to become eventful in a true sense.

Eventful reading

Behind all reading is the desire to know. But there are different forms of knowing, just as there are different forms of knowledge. Knowledge today is commonly thought of as an object; something to be accumulated and stored. Something that we can leave and return to at any time, like an exhibit at a history museum, or files on a hard drive.

There is a different way to think about knowledge. That is, knowledge as an event. Something that is bound to time and which arrives – it is not always already there like abstract knowledge. It happens. It is as an encounter. This form of knowing is alluded to very early on in the Bible. “Adam knew his wife” (Gen 4:1). This is a bodily form of knowing. And if we think about it, there are indeed many things that we know in ways that are not easily put into the language of classification and quantification, a knowing that cannot be separated from an event – a knowing which requires our participation. A novel is a world that we move within. It is a sensory place – all our senses are harnessed in the making of meaning which is the act of reading.

Eventful reading seeks encounter, not as someone with a dead object and not as a disembodied intelligence. Great literature represents a visitation by meaning, and as a visitor, a novel or a poem is a test of the hospitality of the one visited. This points towards something of what is contained in the Christian practice of Lectio Divina.

Hospitable reading

In Genesis 18 we find the story of a visitation. Abraham sits at the door of his tent, squinting under the harsh desert sun, when three men appear. The old man breaks through the lethargy of the heat, he runs to meet his visitors, bowing low to the ground. Abraham addresses his visitors as “my Lord,” recognising the divinity of his guests. After imploring them to stay saying, “do not pass on by your servant,” he attends to them with great generosity, offering water to drink and for washing their feet, and he offers bread for their hunger. Abraham, the ideal host, is later contrasted with the inhabitants of Sodom, who fail to show hospitality to these same visitors.

These visitations might be read as symbols for the encounter with meaning in a text. In Real Presences, George Steiner describes the encounter with a work of art as a “meeting of two freedoms.” The first freedom is that of the artist, to make something. Corresponding to that primary freedom is the freedom of reception. This Steiner characterises as a secondary or lesser freedom, because it is a response – the work of art addresses us, and our response is the way we receive it. It is a freedom because we are free to pause and pay attention to the call of the meaning that is in the work of art. When encountering a work of art, we are free to “turn aside” just as Moses was free to leave the path he was on to get a closer look at the burning bush (Ex 3). It is a lesser freedom because the encounter with the artwork, the visitation by meaning, places the weight of responsibility on the visited.

The visited must respond, for even apathy is a response. The moment that Moses sees the burning bush, he becomes answerable. He can no longer go his way as he would have before being addressed by the sight. The meaning of his journey has fundamentally changed. Likewise, once you have been addressed by a work of art, you become answerable – that is, you are responsible for how hospitable you are to the visitation of meaning.

How do we take up this responsibility?

Epiphanic reading

Abraham represents the ideal host because of his powers of recognition. He recognises his visitor as his neighbour – as one like him – and honours this kinship by empathising with his bodily needs for water, for sanitation and refreshment and for food. But he also recognises his visitor as one unlike him, as one greater than himself – indeed, as the Divine Other.

The text tells us that Abraham is visited by an anonymous “three men.” His response to these men is, however, to the Lord himself. What were the characteristics by which Abraham recognised the divinity of his visitor/s? We are not told. Instead, the text focuses attention entirely on Abraham’s response. We see the identity of the visitor by means of the hospitality of the visited.

The Gospel of Luke gives us another account of hospitality and recognition. Two disciples are on their way to Emmaus. They have been witnesses to the unspeakable events of Jesus’ crucifixion. Walking along, perplexed by and discussing all they had seen, they are met by a man – it is the resurrected Jesus. Again we are not given any details about the appearance of Jesus. But we are told that the disciples fail to recognise him. Even after he teaches them from the Scriptures, they do not recognise him. Pretending that he would be journeying onwards, in an act of hospitality, the disciples implore him, “Abide with us” (Luke 24:29), echoing Abraham’s “do not pass on by your servant” (Gen 18:3). It is in the breaking of bread, in the participation in the Divine body, that the disciples at last recognise Jesus, that “their eyes were opened and they knew him” (Luke 24:31).

The conclusion I have been working towards is to suggest that the encounter with the text is but one form of encounter with meaning and that it is similar to how we encounter the world. We might even say that we encounter the world as a text – and that we are visited by meaning in all of creation. And all of this meaning issues from a sacred source – the Logos, the Word behind all words. For those who learn to encounter the world in this way, everything is alive with God’s glory. This way of encountering both text and world might be described as “epiphanic.” Reading epiphanically could be a training ground for the eyes to see rightly. This is the craft of reading.

G.K. Chesterton writes in The Everlasting Man that, “The most wild and soaring sort of imagination [is] the imagination that can see what is there.” We need imagination to see the world rightly; to see not only what is there, but who is there. The kind of imagination that was the spark of Abraham’s recognition of the divine in the face of a stranger, which lifted the veil from the disciples’ eyes in the breaking of the bread, and helps us lovingly see our neighbour, is indeed the light which gives light to all men, the Spirit who abides with us.