Michael Shipster is a retired British diplomat, whose overseas postings included the Soviet Union, India, South Africa, and the United States. He lives in Winchester.

Chris Mann’s poetry may be viewed here: http://www.chrismann.co.za/home/

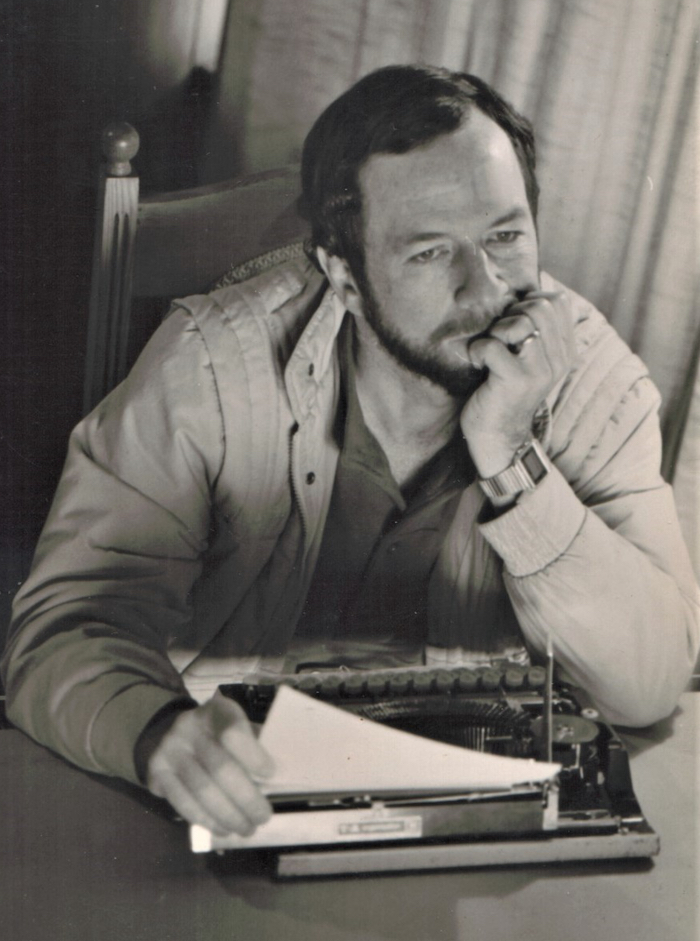

It is a paradox that while poetry in most languages is venerated and sits at the peak of literary achievement, it rarely finds a mass readership. Poetry books don’t sell, poetry readings are sparsely attended; poets tend to be poor. For the poet Chris Mann, who died last March, aged seventy-two, being South African was a further mixed blessing. While South Africa’s tortured history, rich culture and natural beauty were his life-long inspiration, the international ostracism of the apartheid régime, including the arts, prevented all but a handful of South African writers – Paton, Gordimer, Fugard, Coetzee, for example – from reaching an international readership. Even after South Africa opened up following Mandela’s election as president in 1994, the tidal wave of political and social change that followed tended to sweep aside the inclusive, tolerant visions of liberal white writers like Mann, who then struggled to be heard even in their own land.

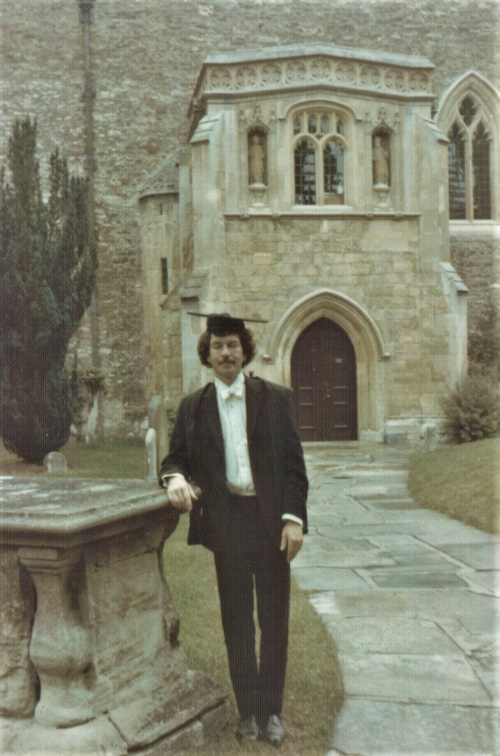

My friendship with Chris began fifty years ago with a chance meeting in the quad of St Edmund Hall, Oxford, where we were both students. Although only three years older than me, he seemed much older, almost of a different generation and I held him in some awe. A Rhodes scholar, graduate of Wits University, veteran of student protests against apartheid, he had completed national service in the South African Navy, spent a year in the US as part of the American Field Service programme and was already a published poet.

As I got to know him I discovered that poetry was not something he did in his spare time, it was already his life’s vocation. While I was an averagely hedonistic, disorganised undergraduate, he had already embraced a strict work ethic to which he stuck for the rest of his life. He rose early, his mornings were sacrosanct, devoted to his writing. I sometimes thought that if our ancient fire trap of a college staircase caught fire Chris would rather continue his hunt for that elusive word or rhyme than grab a fire extinguisher, or even try to escape.

I remember once taking him to my hometown in England, where I had the use of a sailing dinghy. The morning was perfect for sailing and I suggested we leave right away or we would miss the favourable tide. He looked at me as if I had suggested we rob a bank. “I’m sorry, I’m working on something,” he said. “Could it wait till this afternoon?” In vain did I protest that time and tide wait for no man. Not even for Chris Mann the Poet.

Even in later life, when he had developed a strongly Christian outlook, he was seldom able to attend morning services. He worked through family holidays, Sundays, Christmas Day, on the morning of a friend’s funeral, even his own wedding day.

He loved his time at Oxford – the buildings, traditions, the company of learned teachers and students, the opportunity to immerse himself in the literature of the entire world, from Homer and Dante, George Herbert, Donne, his beloved Keats, Blake, Hopkins, Thomas Hardy and Robert Frost to the present. The list is deliberate: these were his most important influences, reaching for the divine through imagery drawn from the ordinary, the natural world and the cosmos. When, in his final year he was awarded the Newdigate Prize for Poetry, (previous winners included Ruskin, Arnold, Wilde, Huxley), he could believe his own work had achieved acceptance and he had found his spiritual home.

As students, talking late into the night, I found it disconcerting that he seemed to be taking mental notes. One risk of being Chris’ friend was that you might later appear in one of his poems. As a poet he was never off duty; he was interested in everyone and everything. He was always watching, listening, observing, trying to understand. He always had a poem on the go, waiting to be born.

He saw it as his mission to use the power, precision and economy of poetry to reveal the world in all its banality, horror, glory, or mystery: a row of potatoes (“their offspring/like thumb-sized moles/suckle in a womb of earth/a tangle of strings”); the State murder of his friend Jeanette Schoon in Angola (“But language … can only gesture, patchily at a/room in shambles, the rafters smoking, freak-/mangled chairs, the hair-tufts, flesh/-bits, your infant’s …”); a dragonfly on a hot rock by the Zambezi (“Your lineage is as old as coal,/your life in the swirl of stars,/a twitch of plasma on a reed”); Christianity and faith (“I saw – sailing through the morning mist/as if through time, your long-hulled ship of stone./That’s when I knew my sturdiest gift for you/would be to raise, in phrase on measured phrase/the small cathedral of a faith-built poem,/made in and out of words, and love, in time”); and on love and family (“And when, growing wiser/you see our imperfections/the frail glasswork of our dreams/remember this: the night/the stars, this blue-quilted bed/were wondrous to your parents./You were conceived in love”).

After Oxford, Chris studied Zulu and African Studies at SOAS, followed by a teaching post in Swaziland, where he became fluent in Zulu, and a lectureship in English at Rhodes University in Makhanda (formerly Grahamstown). It was here that he met Julia Skeen, a postgraduate student whom he married two years later. Julia brought a light-heartedness and capacity for joy into Chris’ life, acting as an antidote to his tendency to introspection and melancholy. Her artwork was a natural partner for his poetic images, especially of the natural world, and she illustrated some of his published works.

In 1980 Chris departed from the poetic stereotype when he became Operations Director at the Valley Trust in KwaZulu-Natal. This took him away from academia and closer to the practical needs and challenges of rural development among the poorest of South Africa. After their daughter Amy was born, followed by Luke, family life became an anchor for Chris’ poetic sensibility, a haven of love and stability that sustained him to the end of his days. In turn, Chris was a loving and morally grounded husband and father, keen to impart his values and learning to his children.

During this period, he began to turn to music to showcase his poetry and reach a wider audience, co-founding a band Zabalaza with Zulu musicians which performed to mixed audiences around the country and on national television. One of the biggest gigs of his life was in 1990 when he performed his poem Till Love is Lord of the Land in front of a crowd of over 100,000 at a rally in Durban to welcome Mandela after his release from prison.

In 1995 Chris moved back to Makhanda to become Professor of Poetry at Rhodes. During the following 20 years he founded and ran Wordfest, a multilingual literary festival which became an integral part of the annual National Arts Festival, seeking to develop indigenous South African literary talent across all its languages. His poetry was adopted for study in the national secondary school curriculum and he developed a following for his live performances in schools and theatres, with Julia providing the images.

After Oxford, despite mostly living in different continents, our friendship remained strong. In 1972, Chris introduced me to his sister Jackie during my first visit to South Africa from Botswana. When Jackie and I were married in Gaborone the following year, Chris and I became brothers too.

In 2020 Jackie was diagnosed with untreatable breast cancer after an already long illness. This hit Chris hard especially since COVID-19 restrictions and his own cancer treatment prevented him from visiting her before she died. Earlier in 2021, after his condition deteriorated rapidly, I travelled to South Africa to be with him and Julia at their home in Makhanda. I was fortunate to be able to spend a few days with him while he was still able to communicate and was at his bedside with his family when he died.

After his death, tributes poured in from friends, colleagues and admirers not only in South Africa, but from around the world. He would have been pleased and surprised to receive so much praise and appreciation. The messages mentioned the magnitude of his poetic vision, his compassion and the skill and sensitivity with which he was able to express the most complex concepts and emotions.

It often takes time after an artist’s death for their contribution and achievement to be fully recognised. I believe that Chris’ following and reputation will grow, and he will achieve recognition not just as a South African poet who navigated his artistic path in difficult and conflicted times, but as a unique voice addressing universal themes, relevant to all.

As for me, I have lost an irreplaceable friend and influence on my life. But the memory and the love, as well as the poetry, will live on.

Hamba Kahle, Chris!

(Go well, Chris!)

The Kirby Laing Centre for Public Theology in Cambridge. Charity registered in England and Wales. Charity Number: 1191741

Kirby Laing Centre, Office 1, Unit 6, The New Mill House, Chesterton Mill, French’s Road, Cambridge, CB4 3NP

© 2025 The Kirby Laing Centre for Public Theology in Cambridge