Andrew White immensely enjoys reading antiquated books, and is a curate at Church of the Lamb in Penn Laird, Virginia.

In his autobiographical essay, “Confidentially,” Abraham Kuyper outlines the circumstances of his conversion to orthodox Christian faith. One pivotal moment is his reading of a popular mid-Victorian novel, The Heir of Redclyffe. Kuyper remarks: “[T]hough not in value, [it] stands next to the Bible in its meaning for my life.” (1) The English novel, a gift from his fiancée, Johanna Schaay, had a profound emotional effect on Kuyper, literally bringing him to his knees in repentance. He notes: “This masterpiece was the instrument that broke my smug, rebellious heart” (50).

Though it was the bestselling English novel of 1853, Charlotte Yonge’s Heir of Redclyffe is little known outside of select academic circles today. In the last century many disparaged the book for its perceived sentimentalism and sanctimoniousness. More recently, feminist critics have dismissed Yonge for her restrictive, traditional views of women. How, then, can the reaction of Kuyper to Yonge’s novel (that it stands next to the Bible) be explained? How did it break the “smug, rebellious heart” of a Dutch intellectual in an age when most in his position were abandoning the tenets of traditional Christian faith?

Charlotte Yonge’s Anglican Faith

Charlotte Mary Yonge (1823-1901), was a prolific Victorian writer, best known for domestic novels portraying middle-class Victorian families. She was also known for her journalistic pieces, biographies (of saints) and essays on the meaning of Christian names. Yonge was mentored by her family’s vicar, John Keble (1792-1866), a leading light in the Oxford Movement, an Anglo-Catholic revival movement that was prominent in the first half of the nineteenth century.

The Oxford Movement (also known as Tractarianism) was influenced by Romanticism, with its tendency to look to the past for practices and values that had been lost because of secularism and materialism. Tractarians were concerned about the growing secularization of the Anglican church and its neglect of its catholic (pre-Reformation) heritage. As a corrective, Tractarians advocated that the church recover some of the doctrine and practices of the pre-Reformation church rather than focus on the theological and ecclesiastical distinctives of the Protestant Reformation. This included a particular emphasis on the Eucharist.

Yonge was the leading novelist of the Oxford Movement and saw her career as a means for conveying its views to English society. Her lifespan is almost identical to that of Queen Victoria (1819-1901). In this sense, then, Yonge was a quintessential Victorian novelist. Though her views were conservative for her time, they reflect an established current of Victorian thought. The Heir of Redclyffe was far and away Yonge’s most popular book (amongst one hundred works of fiction), and the bestselling novel in England in 1853. It was popular in both the British Isles and in America, making an appearance in Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women (1869). It was also the most popular reading choice for young officers recovering in hospital during the Crimean War (1853-1856). By the end of the nineteenth century, Yonge was known primarily as a writer of “girls’ novels,” but her work, especially her earlier work, remained popular among male readers, including William Morris, Alfred Lord Tennyson, William Gladstone, Lewis Carroll and Anthony Trollope. Given the account found in “Confidentially,” Abraham Kuyper, eventual prime minister of the Netherlands (1901-1905), must also be included in this list.

“Two Diametrically Opposed Characters”

The Heir of Redclyffe is organized around the contrasting personalities of two young men: Guy Morville, immediate heir to the Redclyffe estate, and Philip Morville, his cousin (who would inherit the estate in the event Guy produces no male heirs). Kuyper notes this structural element of the novel in “Confidentially”:

The deft touch in this tale lies in its bringing together two diametrically opposed characters. These two torment each other, collide with each other, repel each other, and stubbornly fight through all the complexities of a most interesting family life. At last they are reconciled through the defeat of the stronger and the complete triumph of the seemingly weaker. (51)

At the beginning of the novel, Guy, the “seemingly weaker” character, comes to Hollywell, the home of the Edmonstone family, because Guy’s grandfather, Sir Guy Morville, has just passed away. Guy, who is only seventeen, is taken in by the family since Mr. Edmonstone is his guardian until he comes of age. Guy quickly gains the affection of Mr. and Mrs. Edmonstone, along with their four children: Charlie, Laura, Amabel (Amy) and Charlotte.

Laura and Amy are near marriageable age, but Charlotte is a small child. Guy is warm-hearted, though impetuous and short-tempered. He is a generous character, sensitive and full of integrity. His goodness is internal rather than external, developing rather than set in stone. He owns his own faults with brutal honesty, seeking to temper the darker side of his family heritage.

Philip Morville, Guy’s foil in the novel, is an army officer who is accomplished, well educated, and respected by those around him. Prejudiced by old family rivalries, Philip dislikes Guy from the outset of the novel. He interprets Guy’s impulsive behaviour as the latest manifestation of the Morville family curse, a bad temper which has reared its head at various points in the family’s troubled history. At the same time, Philip feels that it is incumbent upon himself to correct Guy’s shortcomings. Philip constantly finds fault with Guy, undermining his character and position for most of the novel. His suspicion of Guy creates considerable tension in the Edmonstone household because of their growing affection for Guy. Philip’s dislike morphs into jealousy when he suspects that his favourite Edmonstone daughter, Laura, might be falling in love with Guy. Philip declares his love for Laura, an impulsive decision given that there is no clear path for their marriage (considering his economic circumstances). These feelings, reciprocated by Laura, are kept secret for much of the novel.

Head vs. Heart

The contrast which Yonge creates between Guy and Philip reflects the greater value which Tractarians placed on character rather than intellectual achievement, on the heart rather than the head. Guy is sensitive and morally intuitive, having no pretensions to academic excellence. Instead of reading for an honours degree at Oxford, he reads for a pass degree. His Latin is mediocre at best, and he has little knowledge of Italian. Philip, on the other hand, is the embodiment of what the Tractarians stood against. He prioritizes intellectual achievement, though his academic career is cut short by economic pressures on his family. He corrects Guy’s tentative Latin and proudly enjoys reading Italian novels aloud in the original language. In keeping with Tractarian values, there is a heavy emphasis on personal holiness in the novel, on purity of heart. Guy, determined to overcome both the sins of his fathers and his own personal faults, actively seeks forgiveness and reconciliation. Philip’s primary flaws, conceit and self-righteousness, are less obvious than Guy’s and, therefore, more difficult to correct.

Guy’s Gambling? The Great Misunderstanding

The action of the novel comes to a head when Guy is suspected of having gambling debts. Philip’s married sister sees a thirty-pound cheque, written by Guy, being cashed by a notorious gambler. Guy, in fact, has written this cheque for his uncle who has accumulated minor debt. In the meantime, Guy has requested a 1,000-pound advance from his guardian, Mr. Edmonstone, which he intends to give to a new Anglican sisterhood (ch. 15). Based on these circumstances, Philip persuades Mr. Edmonstone that Guy has succumbed to the vices of his forebears. To make matters worse, Guy refuses to defend himself. To explain the cheque would expose his uncle, and to explain the advance would expose Miss Wellwood, the founder of the sisterhood, to the wiles of Philip’s sister who opposes her.

This misunderstanding shapes much of the novel’s remaining plot. Philip, who wishes to prove Guy’s guilt, goes to Oxford to inquire about Guy’s behaviour but is unable to find any evidence of wrongdoing. When Amy and Guy declare their love for each other, Philip tries to stop the marriage because of the damage he feels Guy will bring upon the Edmonstones. He persuades Mr. Edmonstone to banish Guy from Hollywell. Eventually, the matter of the thirty-pound cheque is cleared up with the Edmonstones. Philip, however, still suspects Guy of gambling because of the 1,000-pound advance, suggesting to Mr. Edmonstone (in a letter) that Guy should be put on a period of probation before he is allowed to marry Amy. When the Edmonstones give Guy and Amy their blessing to be married, Philip, out of principle, refuses to attend the wedding.

The Repentance of Philip Morville (and Abraham Kuyper)

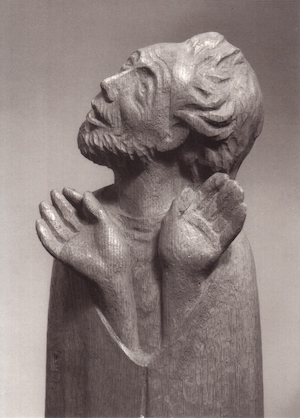

The emotional highpoint of the novel occurs in Italy, when Guy, en route to Venice with Amy, hears that Philip has contracted malarial fever. Guy and Amy immediately go to Recoara to see Philip. Here, as Kuyper notes, the roles of the two characters are reversed: “Philip is now bereft of his world of glittering success, while the sickroom is precisely where Guy can unlock the greatness of his soul” (53). Guy patiently nurses Philip back to health, but, in another reversal, becomes sick himself. In these circumstances, as Kuyper observes, Philip is led “to recognize his own limitations and Guy’s moral superiority,” and this awakens in him “a sense of discontent with his own character” (53). Guy is unable to recover from the fever and is soon on his deathbed. An Anglican clergyman from an English resort town meets with the family members to perform the last rites for Guy. Philip, broken to the core and considering himself unworthy, refuses to enter the sickroom. However, after Amy recites the words of Psalm 51 (“A broken and contrite heart, O God, thou wilt not despise”), Philip enters the room and kneels beside Guy’s bed. Kuyper echoes Philip’s actions internally and externally:

At that moment—I was by myself—I felt the scene overwhelm me. I read how Philip wept, and, dear brother, tears welled up in my eyes too. I read that Philip knelt and before I knew it, I was kneeling in front of my chair with folded hands. Oh, what my soul experienced at that moment I fully understood only later. Yet, from that moment on I despised what I used to admire and I sought what I had dared to despise! (53)

This intense experience, “this internal struggle of soul [which] belongs to the realm of the eternal,” marks the conversion, the palingenesis, of Kuyper the theologian (54). In the novel Guy’s redemptive suffering leads Philip to repentance and the salvation of his soul. Kuyper experiences this vicariously as a reader. Initially, he had been drawn to Philip, whom he describes as his “hero” (53). However, Kuyper comes to see that the “seemingly weaker” character, Guy, is actually the stronger (51).

Christian Elements in The Heir of Redclyffe

Kuyper’s conversion through the reading of Yonge’s novel is not coincidental. The Heir of Redclyffe is infused with Christian themes and typology. The following discussion will focus on two instances: Christlike forgiveness and the Parable of the Publican and the Pharisee.

Christlike Forgiveness

After being falsely accused of gambling, Guy struggles with dark thoughts. In particular, he struggles to suppress his urge to challenge his accuser, Philip, to a duel:

“Guy had what some would call a vivid imagination, others a lively faith. He shuddered; then, his elbows on his knees, and his hands clasped over his brow, he sat, bending forward, with his eyes closed, wrought up in a fearful struggle; while it was to him as if he saw the hereditary demon of the Morvilles watching by his side, to take full possession of him as a rightful prey, unless the battle fought and won before that red orb had passed out of sight. Yes, the besetting fiend of his family – the spirit of defiance and resentment – that was driving him, even now. . . .

It was horror at such wickedness that first checked him, and brought him back to the combat. . . . He locked his hands more rigidly together, vowing to compel himself, ere he left the spot, to forgive his enemy – forgive him candidly – forgive him, so as never again to have to say, “I forgive him!” He did not try to think, for reflection only lashed his sense of the wrong: but, as if there was power in the words alone, he forced his lips to repeat, –

“Forgive us our trespasses, as we forgive them that trespass against us.”

Coldly and hardly were they spoken at first; again he pronounced them, again, again, – each time the tone was softer, each time they came more from the heart. At last the remembrance of greater wrongs and worse revilings came upon him; his eyes filled with tears, the most subduing and healing of all thoughts – that of the great Example – became present to him; the foe was driven back.” (2)

The episode resembles the temptation of Christ, when the devil was driven back by Jesus’ resounding appeals to Scripture. In this scene from the novel, the setting sun reminds Guy of the New Testament warning about anger (Ephesians 4:26). His “vivid imagination” and “lively faith” cause him to picture a struggle between his “true and better self” (“the good angel”) and “the hereditary demon of the Morvilles” (a fiery temper). The intensity of his murderous thoughts jolts him, and he vows to forgive his enemy once and for all, repeating and repeating the line from the Lord’s prayer. Eventually Guy’s heart is softened, and he finds it in himself to forgive Philip for his false accusations.

Guy’s reflection on the “great Example,” the Son of God who resists the temptation of the evil one, enables him to move past his murderous thoughts. In the same way that Jesus resists the hereditary effects of Adam’s original sin, Guy resists the demons of the Redclyffe Morvilles. With the line from the Lord’s prayer — “Forgive us our trespasses, as we forgive them that trespass against us” — Guy is reminded that God’s forgiveness is contingent upon his own willingness to forgive. This lesson shapes the rest of the novel’s action. Guy continues to practise otherworldly forgiveness even as Philip remains unforgiving. This is manifested most clearly when Guy nurses Philip through malarial fever. Here Guy moves from Christlike forgiveness to Christlike sacrifice, laying down his own life for the sake of his inveterate accuser. Through this portrayal of Guy, Yonge suggests that suffering on behalf of others is what constitutes true Christianity. (3)

The Parable of the Pharisee and the Publican

In her earliest plans for the novel, Yonge indicated her intention to contrast two central characters: “the essentially contrite and the self-satisfied.” (4) This closely resembles the Parable of the Pharisee and the Publican in Luke’s gospel (Luke 18:10-14). In Yonge’s novel Philip is equivalent to the proud, self-satisfied Pharisee, and Guy is the sensitive and penitent publican. The reversal of Christ’s parable is that the publican rather than the Pharisee is justified. The double-reversal of the novel is that a penitent Pharisee, Philip, can be justified before God (Colon 37).

Though some Pharisees were hypocrites, the Pharisee of Christ’s parable does not appear to be. His moral complacency is based on actual piety. This is also the case with Philip, who, as a rule, lives an upright life and does not merely pretend to be righteous. Philip does many good things, including giving up a promising academic career (and entering the army) so that his sister could remain in their childhood home. However, his righteousness leads to the sin of self-righteousness. This is more subtle than hypocrisy and Philip’s Pharisaism is not initially evident in the novel. Eventually, Philip’s judgmentalism leads him down the road of the Pharisee in Christ’s parable. Like him Philip is self-assured but not self-aware. Guy, conversely, reflects the penitential qualities of the publican. He quickly owns his faults, particularly his bursts of temper, and seeks to remedy any wrongdoing. This keeps him honest and on a good footing with others. Some critics have disliked the ending of The Heir of Redclyffe, particularly how Yonge prolongs the tale well beyond Guy’s death to recount the gradual reformation of Philip. However, tracing the process of Philip’s repentance and redemption is central to Yonge’s concerns. In the last fifth of the novel Philip emerges as the story’s central figure. He is transformed from the antagonist into the protagonist (Colon 42). Philip, in the end, is the rightful heir of Redclyffe.

In The Heir of Redclyffe Charlotte Yonge’s desire to depict English family life and relationships is secondary to her goal to challenge the reader’s moral complacency (Colon 32). Her primary purpose is to critique Pharisaism, to expose, through three-dimensional characters and a complex story, the sins of self-importance and self-righteousness. It is not coincidental, then, that Abraham Kuyper was converted by The Heir of Redclyffe. Susan E. Colon has argued that the “truest interpretation” of the novel “comes in the reader’s imitative enactment of the repentance of Philip” (44). This is precisely how Kuyper interprets the novel. Yonge’s condemnation of Philip’s self-righteousness cuts Kuyper to the quick and he is literally brought to his knees. Yonge did not wish to change minds through her novel — she was aiming for the heart. This accords with Kuyper’s description of his own conversion, which he says, “was not a gradual shift from childlike piety to a sweet sense of salvation, but rather demanded a total change of my personality — heart, mind, and will” (Confidentially, 47).

Conclusion

Kuyper’s conversion story dramatically illustrates the affective power of literature. It is a travesty that Yonge’s massively popular novel is out of print in 2021. This is due, in part, to the critical condescension Yonge’s work endured for much of the twentieth century. Modern criticism has tended to dismiss Victorian moralizing as compromising literary achievement. As Gavin Budge argues, however, “to assert that expressions of religious commitment are necessarily inimical to a work’s status as art is to make an a priori assumption that the domain of aesthetics necessarily excludes questions of morality.” Though committed to a robust Anglican faith, Yonge’s novel never tells readers what to believe or how to behave. Instead, Yonge uses the words and actions of her well-developed characters to dramatize her beliefs and values. The tale of Guy’s self-sacrifice and Philip’s repentance captured Kuyper’s heart and changed him forever. In his dramatic conversion, we are reminded of the crucial role that imaginative storytelling can play in the proclamation of Christian faith.

Get the latest issue in print or subscribe for the next three.