Dr Nigel Halliday, an Associate Fellow of the KLC, is a retired pastor and Bible teacher who has now returned to his first love of art history. He is currently researching the influence of the Reformation on the later work of Michelangelo.

In Western culture “art” usually comes with at least an implied capital A and points to a narrow range of activities: painting and sculpture, music and ballet, literature and theatre. We may debate whether some other activities – architecture, photography, pottery – can be admitted to the category, but this still accepts a concept of “art” as narrow, limited, specialised.

But, as Nicholas Wolterstorff points out in Art in Action ([Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1980], 6), this way of thinking dates back only to the Enlightenment. Before then, if music was in a category with anything, it would be with mathematics; and up to the Renaissance, no one would bracket painting and sculpture, where people got their hands dirty, with the noble activities of poetry and philosophy.

Art with a capital A has sadly marginalized the arts in daily life. The Enlightenment, with its love of reductivist definitions, came to define real art as something to be appreciated only aesthetically, not serving any practical use. Art in its purest form was literally useless. (1) And as the appreciation of art tended to revolve around cultured education and money, most people had to get on without it, and did so. Meanwhile, the Artist, with a capital A, took on a special role with quasi-prophetic powers. Everything they did tended to be described as a “masterpiece,” as if Rembrandt or Tracey Emin never had an off-day, and their works are shown in church-like galleries, worshipped in reverent silence and awe.

The Bible offers a completely different way of thinking about the arts which brings them back into the orbit of every one of us in everyday life. The starting point is not “art” but creativity. We are made in God’s image to be, among other things, creative – all of us. (2) Rather than thinking of art in terms of a league table with painting, sculpture or music at the top, and origami, lace making and flower arranging locked in a battle to avoid relegation, we can picture something more akin to a wheel, in which creativity is the hub and all art forms radiate from it as spokes.

This is not to suggest that all are equal in every respect – my fifth reason below will sing the praises of the “Fine Arts.” But it recognizes a prior truth: that we are all made to be creative, and human creativity takes many important and valuable forms in enhancing the richness to our lives.

1. God has made us to be creators

When we say that God has made us to be creative, the distinction is often hastily added that God created ex nihilo, whereas we create out of what God has already made. This is obviously true, but the distinction may be overegged. In our creativity the Lord himself has encouraged us to imagine and make new things, ones he has not made. God himself was interested to see what Adam would name the animals, a task presumably involving insight and creative imagination (Gen 2:19); and as Francis Schaeffer points out in Art and the Bible ([London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1973], 14), God ordains that the decoration of the priestly garments to be worn in his tabernacle should include blue pomegranates, a combination he had omitted from the natural order (Ex 28:33).

Not all of us are a Rembrandt or a Mozart, but God has made each of us to be creative. Our creativity can be entirely unserious, such as doodling, whittling a stick or making daisy-chains. And it does not have to be divorced from utility: we can use our creativity in how we dress, speak, cook, decorate our homes or arrange our window boxes.

Art, in the basic sense of creativity, is not an activity for gifted specialists, nor a luxury added onto life for those wealthy enough to have the time and leisure to enjoy it, but it is intrinsic to every human life. It is important to remind ourselves of this, to pay attention to the gifts God has given us with which to add to and enrich the delights of his world.

2. The arts and crafts help us pay attention to the world

Crafts invite us to take an interest in the world God has made. They encourage us to be present to our everyday experience: to notice colours and colour combinations, to pay attention to textures and shapes, to explore and celebrate different materials, and to imagine how to use them to make new things. This is also true of the fine arts, discussed below. Whatever else pictorial artists do, they help us to see the world around us: those who draw and paint will notice things in the everyday and draw our attention to them by depicting and framing them.

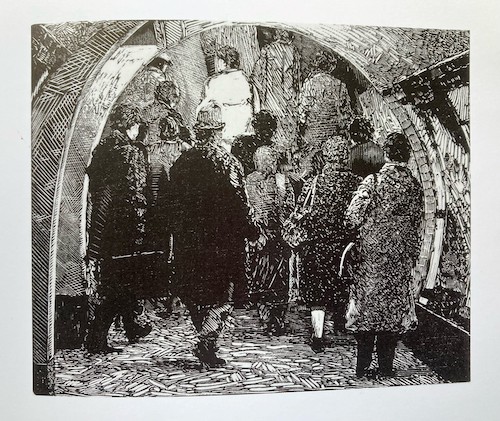

For part of his career, my friend, Peter Smith, made woodcuts of the London underground system – not the trains and tracks, but the passageways and staircases, parts of the system that normally we pass through as quickly as possible, taking in as little as we can. But Peter’s woodcuts invite you to slow down and notice your environment, the shape of the tunnels, the clothes of your fellow commuters. And after a while I found myself in the underground system seeing it as “a Pete Smith.”

I wonder if this is part of how we “subdue the earth,” especially in overcoming the sense of alienation we experience because of the fall. As art helps us to notice and to look, it helps us to be more at ease with our surroundings.

3. The arts and crafts are an expression of love

God is love, and therefore we should expect to find love shot through all his creation. The arts and crafts involve an often-unconscious expression of love, a kind of unconditional appreciation. To spend your time making a tapestry, sewing clothes, crafting a sentence, is to say, “I care about this. This is valuable. This is worth the devotion of my time and attention, and worth your attention.”

In a downstairs gallery of the Wallace Collection in London is a wonderful collection of mediaeval carvings in wood and in ivory. I have often stood and looked for a long time at these, not just wondering at the skill of the artist, but enjoying the warmth of the humanity that said that this was a worthwhile thing to make.

Conversely, some years ago I saw the work named Hell by Jake and Dinos Chapman. It consisted of small-scale but extensive models of battlefields, covered with bodies made from toy soldiers, each intricately wounded, many disfigured. I felt it to be a genuinely horrible work. One might even call it perverse, because the only expression I could find to describe how it had been made was “with love” – that dedicated care and attention we give to things we value, but here devoted to unmitigated suffering and horror.

Another aspect of the way love permeates the arts and crafts is that we want to share them. From the youngest children who proudly show us their drawings to the craft maker or artist showing their work on the local Art Trail, we want to share our creations with others. Indeed, we often struggle to evaluate our creations until someone else has seen them. As Ellis Potter observes: “Relationship precedes identity” (3 Theories of Everything [Destinée Media, 2012], 54). So with the arts, the work needs to be seen to take on its true character.

4. Beauty is a powerful apologetic for the gospel

But then beauty is a subject of its own. From very different parts of the philosophical world, Calvin Seerveld (in Bearing Fresh Olive Leaves: [Carlisle: Piquant, 2000], 106ff) and Roger Scruton (2–3) both warn against a glib embrace of beauty in art, since beauty can be deeply corrupt. That famous, non-biblical trinity of goodness, truth and beauty is one we need to be wary of: not everything that looks beautiful is necessarily good and true. Nevertheless, beauty is a major factor in our enjoyment of art and craft, and it is, I believe, a powerful apologetic for the Christian gospel.

Our experience of beauty is predicated on difference: we perceive beauty in something that is other than ourselves, something that presents itself to our attention. (3) But, as Ellis Potter observes, and Christopher Watkin has recently reinforced in his Biblical Critical Theory ([Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2022], chapter 1), difference is a major problem for most systems of thought except Christianity.

All religions and philosophies, Potter argues, are monist, dualist or trinitarian. Islam, Buddhism, Hinduism, pantheism, atheism, all at root see reality as being, or tending towards, oneness. Taoism and Confucianism see reality as dualist, an eternal struggle between two equal and opposing forces, which in perfect balance would resolve to oneness.

The biblical explanation of reality is quite different. It explains that reality is made by God who is himself a trinity, three distinct persons linked in perfect loving unity: diversity in unity underpins the nature of the created order. It is only the trinitarian explanation that really accounts for our lived reality, for personhood and relationality, for difference which is real and good.

In a monist universe, it is hard to see how novelty comes about, and particularly why it would be celebrated in art and craft, since it fosters difference. But in the trinitarian explanation of reality, where diversity exists within unity because love encompasses all, the multiplication of new things through the arts and crafts makes perfect sense and is something to be enjoyed.

Where human creativity points to the truth of the Bible, how much more does beauty. For beauty is essentially relational: it involves an encounter between the perceiver and something outside themself. Indeed, Roger Scruton suggests it is a two-way encounter: like mutual gift giving, the object offers itself to us, and we in turn

give it our focused attention. He compares our enjoyment of beauty to our enjoyment of being with friends: pleasure mixed with curiosity to understand more about the other (Scruton, 26).

And beauty is not just an I-Thou relationship: it also implies a three-way relationship. Although we may disagree on matters of taste, our judgements of beauty imply something objectively real in the object of our attention, which we assume that others can agree on. We can enjoy a rainbow or a sunset on its own, but if our loved ones are indoors, we are very likely to encourage them to come out and enjoy it too. We can enjoy the beauty of a painting on our own, but if we are in company, we are likely to discuss it together.

5. Fine Art is a distinctively Christian form of creativity

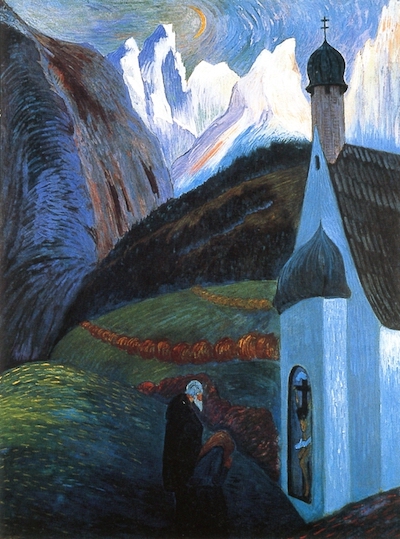

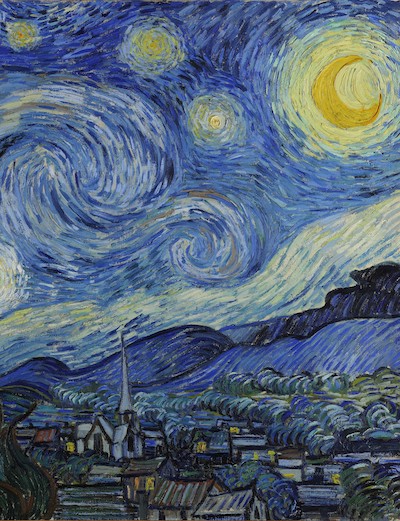

What is often called “Fine Art” seems to be a uniquely Christian contribution to world culture. It is noticeably absent from, or even actively forbidden, by other cultures. Arising out of the tradition of Byzantine icons, the Western practice of image-making, especially in painting and sculpture, invites us to meditate on our deepest values and commitments. (4) Artists use a variety of aesthetic components, such as composition and balance, light and shade, hard or soft lines, degrees of realism or obvious artificiality, in order to steer our contemplation, but we are left with a degree of latitude to meditate on the meanings and implications of the work.

In his work on literary realism Mimesis ([Princeton University Press, 1968]; see e.g., 49), Erich Auerbach compares biblical narratives to those of Greek myths, and shows how the biblical ones are constructed in such a way as to invite readers to inhabit the story, because it deals with matters that directly impact their own lives. In the same way, the Western fine art tradition produces images that directly address the viewer, inviting us to step into a world that may or may not resemble the world

we live in but is in any case sharply demarcated from it by the frame, and to imaginatively engage with what we are shown there.

The fine arts are a reminder that we live with an unseen reality, involving truth, meaning and morality. Many works of art engage directly with matters of faith and value, through depictions of biblical events or historical or mythological scenes. But even a simple landscape or a domestic interior is a recognition of value, that we are not surrounded by meaningless stuff, as would be the case if atheism were correct, but by a created order that evokes responses that go far beyond the physical.

Fine art, arising from a Christian trinitarian understanding of reality, celebrates imagination and novelty, confident that engagement with our deepest values is not just a matter of law keeping or definition by words, but engagement with the whole self through reflection and worship. It has been an interesting feature of our culture to watch how art, having been put on a pedestal by the Enlightenment as a path to transcendence but unable to fulfil that role, has toyed with ugliness or indifference, and attempted to dismantle the boundaries between art and life. The frame is seen as a constraint against freedom, the highest value of the Enlightenment, but the result of such “freedom” is essentially monist – losing distinctions between art and daily life, and making things less rich and interesting, not more so.

The biblical understanding of the arts and crafts, however, encourages an enrichment of life through a celebration of what God has made, and of who he has made us to be, and helps to bring us together through creativity, beauty and reflection.