INTRODUCTION

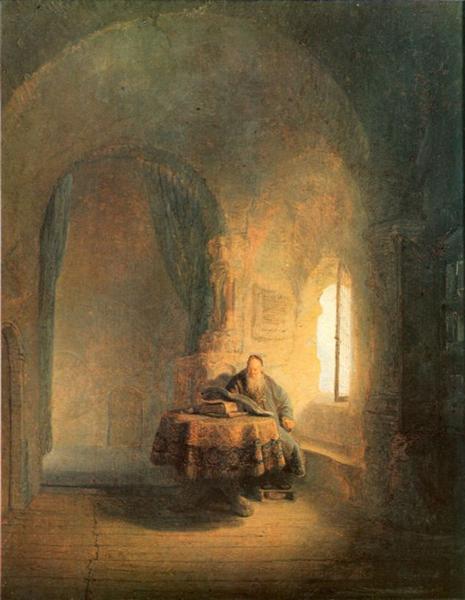

It is wonderfully serendipitous (providential) that in the year that Herman Bavinck died John Stott was born. Both are colossal figures whose gift has still to be fully received and who remain as relevant as ever. Both were brilliant academics, both spent time in the pastorate, but whereas Stott elected to stay in the pastorate while writing a series of important books as an “organic intellectual,” Bavinck left the pastorate for the seminary in Kampen and then the Free University of Amsterdam. I do not know if Stott ever read Herman Bavinck, but he was certainly aware of his nephew J. H. Bavinck’s work on mission. In a day in which the gap between the academy and the church often feels like a gulf both Stott and Bavinck model a healthy relationship between the two.

Bavinck was first mediated to me at seminary through the standard textbook for theology in Reformed seminaries, namely Louis Berkhof’s Systematic Theology. I was also given Bavinck’s Doctrine of God as a gift. Both were published by Banner of Truth which is typically associated with the Puritan Reformed tradition. I do not recall either having a significant effect on me at the time. It would be years before I realised the profound significance of Bavinck as a theologian. Here are five reasons to read Herman Bavinck today:

1. BECAUSE THEOLOGY MATTERS

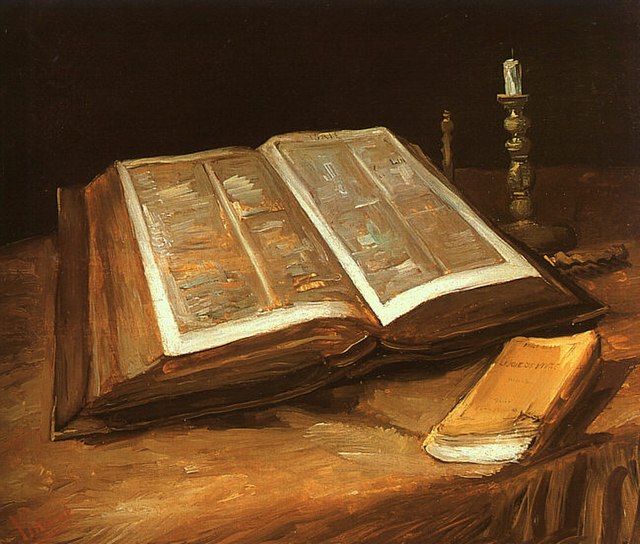

In his wisdom God did not give us a book of systematic theology. While the Bible is rich with data for theology on every page, it is not a book of systematic theology. Theology typically sets out the loci of Christian belief – the doctrine of God, the doctrine of creation, the doctrine of the human person, the person and work of Christ, the doctrine of the church, etc. – in logical order, and this is not what we are given in the Bible. A way of thinking of the Bible which I find helpful is as the deposit like the silt in a river of God’s immersion in the life of Israel, culminating in the Christ event, and then on to the mission of the church. It is this grand, sprawling, capacious metanarrative of a book, as Eugene Peterson describes the Bible, that is our authoritative, fully trustworthy text, and not creeds, confessions or theologies.

Nevertheless, from its inception the church has found theology to be an indispensable servant of the church. In responding to critics and heretics and for our own integrality we need to be able to summarise and set out logically what we believe, and this task is admirably and vitally performed at different levels by creeds, confession and systematic theology. Biblically, we might say, theology responds to the call for us to give a reason for the hope within us. Historically, theology has thus performed two major tasks: it attempts to systematise what Christians believe on the basis of the Bible in particular, and in dialogue with the history of Christian thought (tradition). Secondly, it performs the apologetic task of responding to the great questions of the day.

These tasks are indispensable to the mission of the church, not least in a day in which the core beliefs of Christianity are under threat within so many mainline denominations. Every Christian ought to have a vested interest in good theology. It matters! Sometimes one gets the impression that we move from the Bible to theology – which is true – and then it is in theology that we really find our authority. However, it is worth remembering that John Calvin wrote his renowned Institutes in order to help people read the Bible better, a service that good theology performs well.

And in Bavinck we find very good theology. In his university studies at Leiden University, Bavinck had done considerable work in Semitic languages, and, unlike much theology today, his work is grounded in Scripture as God’s authoritative Word, and he circles back to it continually. Indeed, Bavinck recognised the need for comparable work to be done in biblical studies in his day. As a stopgap he arranged for Matthew Henry to be translated into Dutch. Bavinck’s theology is orthodox but extraordinary in the range of its engagement with the Christian tradition and contemporary thought. Bavinck had studied at Leiden under some of the leading Enlightenment theologians and biblical scholars of the day, and his work lacks the mentality of the enclave that too easily shapes some Evangelical theology today.

2. BECAUSE GRACE RESTORES NATURE

If you look into the engine of any theology, you will find certain basic elements that drive and shape the entire theology. These elements answer the fundamental question: What is the relationship between redemption/salvation and creation or how does grace relate to nature? Both Abraham Kuyper and Bavinck saw with crystal clarity that grace restores nature or that redemption/salvation is the recovery of God’s purposes for his creation. Creation has been disfigured and distorted by sin and grace is like the medicine that heals this sick patient.

Although more and more theologians are converging around this insight, it cannot be taken for granted. Historically, different answers to this question have been given, answers which typically devalue the materiality of created life and the comprehensiveness of salvation. In too much Evangelicalism, for example, a sacred/secular dualism continues to hold sway in which grace relates primarily to my individual salvation and to the life of the institutional church and evangelism. Bavinck never for a moment undermined the importance of these issues but, through his grace restores nature paradigm, he resituated them within the grand story of the Bible, thereby giving us a far bigger view of the trinitarian God, creation, redemption, salvation and mission.

Sometimes theology appears irrelevant because it is! But this is not the case with a theology like Bavinck’s, shaped internally by grace restoring nature. It opens out onto all of life and thus is wonderfully relevant to the material realities of our daily lives in all their dimensions.

3. BECAUSE THEOLOGICAL ETHICS MATTERS

A theology shaped by grace restoring nature flows naturally and inevitably into ethics. Bavinck had a lifelong concern with ethics. His doctorate focused on the Swiss Reformer Zwingli and his ethics and after the publication of his multivolume Reformed Dogmatics he worked away on a book on Reformed Ethics that was never published in his lifetime. Wonderfully, this manuscript came to light again in recent years and is now available as his Reformed Ethics in two volumes in the English edition.

Oliver O’Donovan is one of the best theological ethicists of our day. His recent trilogy is entitled “Ethics as Theology.” Bavinck would have said a loud Amen to this series’ title. His Reformed Ethics does extensive theological work before moving to ethical issues. Ethics emerges out of theology and theology is incomplete without ethics. If faith, as the grace restores nature paradigm implies, relates to all of life as God has made it then how we live coram Deo in every area of life requires sustained attention. Ethics is thus no marginal addendum to theology but flows out of its heart.

Bavinck recognised the need for a theology that opens out onto all of life but never made the mistake of thinking that theology was the only Christian discipline. This insight underlay part of his frustration of teaching at a seminary. The good news of Jesus called for hard Christian work in all the disciplines and hence Bavinck saw the vital importance not only of seminaries but of universities, and, in particular, Christian universities like the Free University established by Abraham Kuyper and friends, to which Bavinck eventually moved as Professor of Theology. Bavinck himself also made substantial forays into psychology, education, science and social analysis.

In a different way but equally important, John Stott came to see the missional importance of ethics and ethical apologetics. I still remember the excitement I felt living in apartheid South Africa when Stott’s Issues Facing Christians Today was first published. If anything, the need for such work today has increased exponentially as the church is confronted with fast-changing societies and unprecedented ethical issues. Human and creational well-being is at stake, and so too is the glory of God. Neither Stott nor Bavinck ever made the mistake of reducing God to being all about us. Yes, God is gracious and loving beyond measure and has our best interests at heart, but ultimately it is all about the glory of God, as it should be.

4. BECAUSE PHILOSOPHY MATTERS

Karl Barth, although often denigrated by some Reformed Evangelicals, must rank as one of – if not the – greatest theologians of the 20th century. Almost single-handedly Barth brought the liberal theological edifice tumbling down, and his rich theology is deeply engaged with Scripture. I am not a Barthian but learn from him repeatedly. I wonder how Kuyper and Bavinck might have engaged with Barth and Dietrich Bonhoeffer? I have no doubt they would have read them closely and engaged with them rigorously.

In my view, a serious deficiency in Barth is his rejection of worldview and philosophy. The result is that theology in his tradition tends to be kept within the theological silo and not tooled for, or allowed to spill over into, other disciplines. Both Bavinck and Kuyper do not make this mistake. Both embraced the importance of a Christian worldview, and both recognised the importance of Christian scholarship in philosophy. To a major extent this recognition underlies the extraordinary resurgence in Christian philosophy we have witnessed in recent decades.

When Bavinck came to give the Stone lectures at Princeton Seminary he chose as his topic The Philosophy of Revelation, a sign of just how seriously he took philosophy. In my early years as a scholar, Kuyperian friends told me that if I wanted to be a Christian scholar I needed to do work in philosophy. This was good advice and on a daily basis I remain grateful for work in philosophy and its contribution to my work in biblical studies, theology and ethics. In my view both theology and philosophy are foundational disciplines, each drawing on the other as they become more systematic, so that Christian work in both is vital for the project of Christian scholarship.

5. BECAUSE MORE OF BAVINCK IS NOW AVAILABLE THAN EVER BEFORE

In this centenary year of Bavinck’s death, his work is surely better known than it has ever been. The translation by John Bolt and colleagues and the publication of Bavinck’s multivolume Reformed Dogmatics by Baker Academic were seminal events which have sparked a major renewal of interest in him as a theologian, ethicist and more. More recently his Reformed Ethics was published and more and more of his writings have become available in English, as well as being translated into other languages. His Our Reasonable Faith has recently been reissued as The Wonderful Works of God. Alongside this the secondary literature on Bavinck continues to grow. We have long needed a substantial biography of Bavinck in English and now that too has been provided in James Eglinton’s Bavinck: A Critical Biography (Baker Academic, 2020). Eglington’s book is well researched and written in a lucid and accessible style, providing the narrative we need to understand Bavinck better.

Both Stott and Bavinck have bequeathed to us a feast, a feast that we need today. Both were orthodox believers, and both found in their very orthodox belief the imperative to engage in depth with the cultures of their day. As the Kirby Laing Centre embarks on its journey of public theology amidst often dark days, it is such figures who will light the way.

Dr Craig G. Bartholomew is Director of The Kirby Laing Centre.

The Kirby Laing Centre for Public Theology in Cambridge. Charity registered in England and Wales. Charity Number: 1191741

Kirby Laing Centre, Office 1, Unit 6, The New Mill House, Chesterton Mill, French’s Road, Cambridge, CB4 3NP

© 2025 The Kirby Laing Centre for Public Theology in Cambridge