Istine Rodseth Swart reviews the book by Craig G. Bartholomew and Paige P. Vanosky (Downers Grove: IVP, 2021). Istine is an administrator for the KLC.

All Are Invited

The 30-Minute Bible is an invitation to read and understand the Bible, that strange library of books that “is not just another story. It claims to be the true story of the whole world, and it invites us to make it our story” (178). If this claim is valid, then the Bible is an invitation to everybody – “us.” This is evident from the conduct of Jesus who, while on earth, engaged with and proclaimed the good news to the schooled and the unschooled, the ordinary citizen, even the outcast: the learned Nicodemus, the fisherman, the Samaritan woman at the well. In our time, the Bible and a book telling its story is likewise intended for all: the professor and the student, the pastor and the congregant, the billionaire and the homeless person, the regular you and me.

This book is suitable for those who are unfamiliar with the Bible, but it is not an invitation to the daunting task of reading the Bible verse by verse, though immersion in the whole Bible is a desirable goal. Rather it tells us why the Bible is important for every person; for all who engage with the fundamental questions: “What are human beings and why are we here?” (23); Why is the world so broken and why can we not fix it – or our broken selves?

A strength of this book is that the authors face these questions squarely and offer scholarly, yet simply and clearly formulated perspectives on the answers revealed in the biblical narratives, while acknowledging that there is much that is only partially understood. (Additionally, the book is attractive and relatively short and asks for only thirty minutes of our time per day for a month.)

One such perspective presented is the centre-stage position of God in the biblical drama: He is the creator God who set up the earth as the ideal home for humankind; who deemed his creation to be good and did not abandon it when it became tragically and catastrophically tainted through the rebellion of his creatures.

Relationships

The authors navigate the creation, fall and God’s great redemption plan through the Old Testament to its culmination in the New Testament; considering how God’s interaction with humankind is aimed at redeeming all of creation, (1) motivated by an unwavering desire to be in relationship with the work of his hands.

Their argument for the primacy of relationships resonates with our life experience: our greatest joys derive from meaningful relationships; our deepest despair from broken ones. We are created in the image of God, created to be in relationship with God, ourselves, one another, the world and what lies beyond its confines.

Through the death and resurrection of Christ, in particular, God’s love for us is readily discerned in the NT, but it is less obvious in the OT. The authors help us to look at the OT through the lens of God desiring to restore relationships with his creation by, for example, emphasising the significance of the tabernacle – as evidence of God desiring to dwell among his people, the Israelites. An Israelite could say: God is my neighbour!

Although God’s love was expressed in his desire to live among his people, his love is not unconditional: he gave his prospective neighbours the Ten Commandments and rules by which to approach him. The former, a description of the ethos of a good neighbourhood, was and remains a reminder that this is God’s world, designed to work in a certain way, a way of being that eases our existential angst: “We find life when we submit to God and follow his ways in his world” (26).

Redemption for All of Creation

This is also a book for those who are familiar with the Bible, but who may benefit from succinct presentations of important perspectives, notably the emphasis on the bigger purpose of our salvation beyond personal redemption. The authors question the view held by some that “the Bible is all about letting go of this world and heading for heaven as a disembodied soul, as fast as possible!” (118). A broader view of salvation is presented, one that encompasses relationships with fellow humans, society and all of God’s creation so that what was once pronounced to be “good” by the creator will be restored.

In the NT we see that through the indwelling Spirit, we are more than God’s neighbours, we are his address – his church is his address. When we move beyond this already-but-not-yet time, we will dwell with God in immediacy in the radically renewed heaven and earth, where “Evil is eradicated once and for all, and heaven – God’s place – comes down to earth so that heaven and earth are now one” (182). Thus, the authors claim: “This is unique, epochal news on a truly cosmic scale” (138).

Presentation

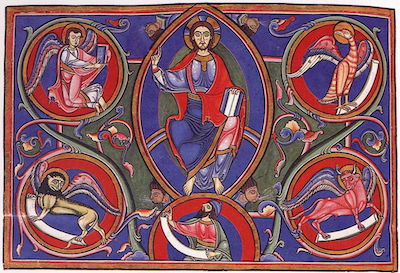

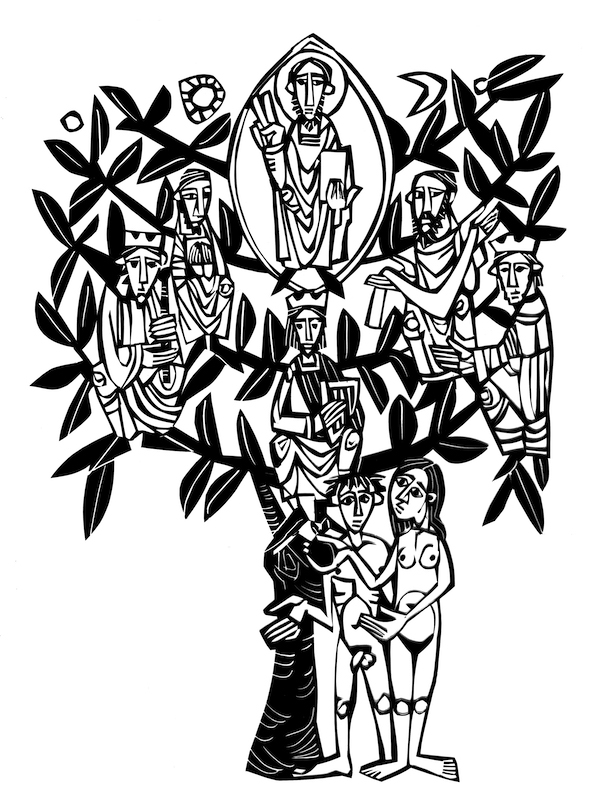

If the strength of the book lies in its perspective, then its charm lies in its presentation, specifically in the woodcut illustrations by Brother Martin Erspamer, OSB, a well-known liturgical artist. He is motivated by the Benedictine ethos – that God may be glorified in all things – which resonates with the intentions of the authors. That these images are an integral part of the book is well illustrated by the evocative depiction of “Out of Eden” (33). Rich in symbolism, it links the inception and culmination of the creation story through a contemporary rendition of the traditional “Christ in Majesty” icon. The tree of life supporting the figures and echoing a menorah is a noteworthy feature.

In addition, diagrams and maps are included to aid understanding, the latter reminding us that the Bible has a context that we cannot ignore when its story is told.

The telling of the story in six acts takes us on a journey from the creation (1st act) and the subsequent fall (2nd), through the initiation of God’s salvation plan (3rd) and its accomplishment in the coming of the King (4th), progressing to the spreading of the news of the King (5th) and culminating in his return (6th) at the “End that is no end” (chapter 30), with selected Bible readings included in each chapter. (2)

I do have some concerns about style: A few of the examples and analogies used in the book will not be familiar to all its readers and others may become dated. This is inevitable when making a book relatable: it is notoriously difficult to choose universal examples that will be true for all time. Swopping the narration between the authors jars at times, nevertheless, the simplicity and immediacy of the language of the telling not only makes the story of the Bible accessible, it underscores that the God of the Bible (though far beyond our comprehension) is accessible.

Get the latest issue in print or subscribe for the next three.