Craig Bartholomew is the Director of the KLC.

The theme of this edition of The Big Picture is journalism. Journalists are our storytellers, investigating what is going on in our cultures and reporting back to us. There is a good reason why the Victorian writer Thomas Carlyle called the press “The Fourth Estate,” the other three being the executive, the legislative, and the judicial branches of government. For a democratic society to flourish, a healthy press is essential. In a democracy government is by the representatives of the people, and the people need to know what is going on if they are to elect good leaders. One of the main ways in which we learn about all that is going on in our and other countries is the press, through the work of journalists.

In the West it is widely acknowledged that the Fourth Estate is in a crisis. Doubtless there are many reasons for this. The communications revolution has brought many benefits, but it has also facilitated the telling of stories by every and anyone, far too often without any investigation. As I note in my editorial, part of the unravelling of modernity has been the calling into question of the very possibility of “truth,” so that we are reduced to “your truth” and “my truth.” The internet and the media revolution have facilitated echo chambers in which we only hear what we want to hear and already believe. In such a context of the surface (see Jean Baudrillard on postmodernism) and the instant there is less and less room for the costly, slow, hard work of investigation.

The instant and the uninvestigated are the enemies of the truth. The release of the redacted affidavit justifying the search of Mar-a-Lago is surely newsworthy but there is something disturbing about major news outlets reporting on it even as they try to read it. The instant also plays to the trivial and the titillating. Do we really need endless reports either slagging off the Sussexes or celebrating them? The right wing responses to the search of Mar-a-Lago also revealed the danger of the uninvestigated. Seeing politicians and others spreading all sorts of conspiracies without any evidence or investigation is downright dangerous.

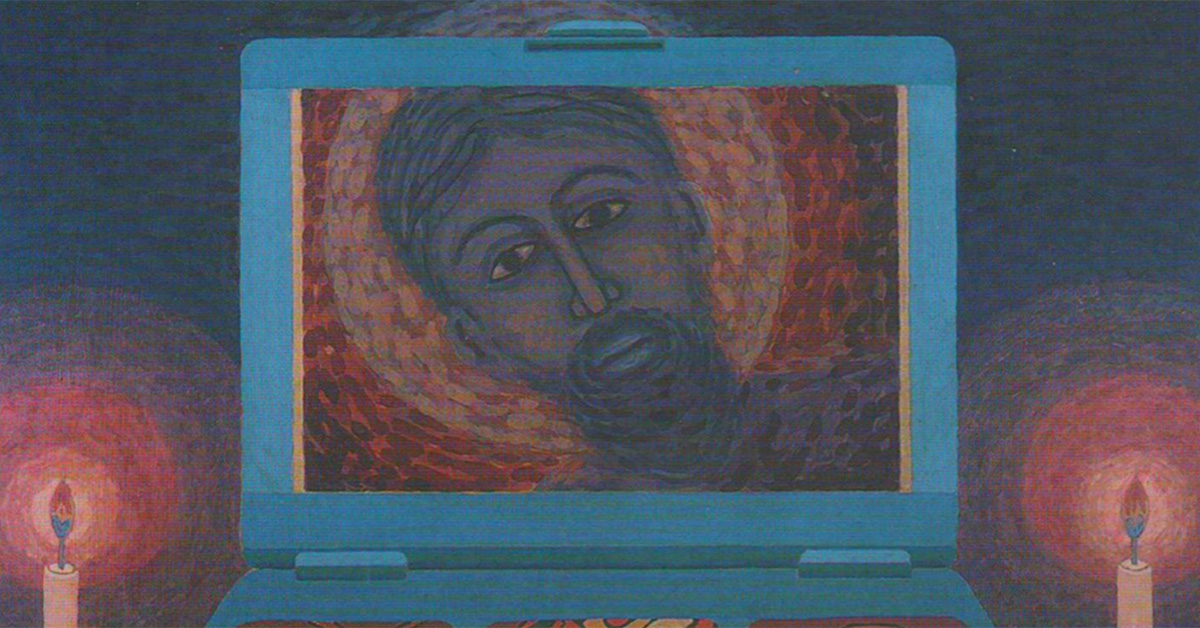

We desperately need healthy, investigative journalism but clearly it is not a priority in our cultural moment. If we are to retrieve investigative journalism, we need exemplars that we can hold up to future generations, encouraging them to do likewise. In this piece I commend to you Ryszard Kapuściński (1932–2007) as one such exemplar. Here are five reasons for reading Kapuściński’s readily available books.

1. Because he immersed himself in what he wrote about

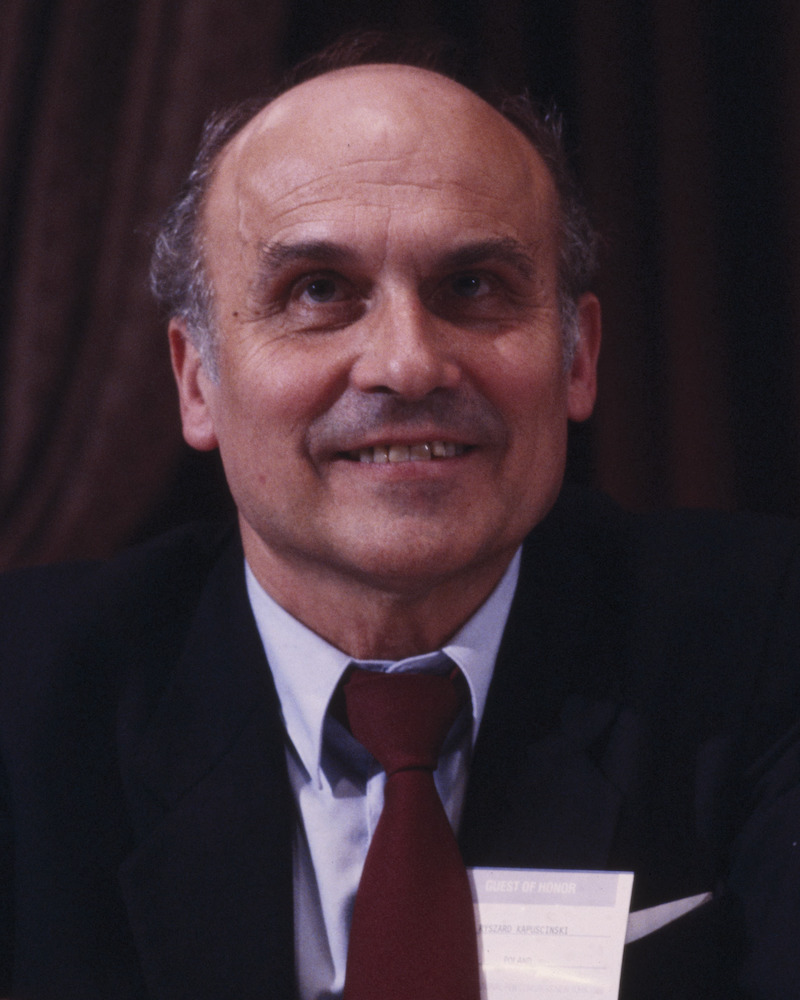

Kapuściński learnt from the Polish born social anthropologist Bronisław Malinowski that “to judge something, you have to be there,” what we might call journalism through immersion. Read any of Kapuściński’s books and you will soon realize the extent to which he went to understand situations on the ground. His most well-known book, The Emperor: Downfall of an Autocrat (Penguin, 1983), for example, emerged from his settling into Addis Ababa to locate and interview the courtiers of the recently deposed Emperor of Ethiopia, Haile Selassie. After the revolution, when most Westerners were getting out, Kapuściński went back in, located an old acquaintance who had been an official in the court, and through him found survivors who had served in the royal court. The result is that, as Neal Ascherson says in his “Introduction,” The Emperor is “not simply the history of the fall of the Ethiopian crown. It is something much rarer in our own epoch: the anatomy of an imperial court, the dying years of a monarchy as they were seen by courtiers” (viii). If you want to taste absolute rule, here is the book that will serve up the meal.

Amidst the renaissance of authoritarianism in our day there are lessons to be learned. Haile Selassie presided over all promotions at every level in his kingdom. Describing the rituals of such promotions, Kapuściński writes: “A special human bond, constrained by the rules of hierarchy, but a bond nevertheless, was born from this moment spent with the Emperor, when he announced the assignment and gave his blessing, from which bond came the single principle by which His Majesty guided himself when raising people or casting them down: the principle of loyalty” (31). If this sounds oddly familiar, it should.

2. Because he celebrated and transcended the limitations of his context

I can imagine a conversation between a teenager and her parents about her desire to become an investigative journalist. “But there is no demand for them anymore!” “How will you earn a decent salary?” “It’s far too dangerous!” Kapuściński is instructive in this regard. He was Polish and he attended university in Warsaw when Stalinism was at its height. When you think of the propaganda and utter brutality of the Stalin era and the travel limits for a Polish journalist it is surprising that he ever achieved a fraction of what he did.

In an astonishing way Kapuściński celebrated and transcended his limits. He reported on both the local (Poland) – he wrote extensively about Pinsk, the town where he was born – and the global. He says of Pinsk that “this very provincial town, this town of dirt roads, cut off from everything, was in fact an extraordinary cosmopolitan gathering” (The Soccer War, Granta, 1990, 235). He could not travel and report from the West, but he could travel in the majority world and this he did with a vengeance, personally witnessing some 27 revolutions. As he delightfully notes, “I was full of stories” (The Soccer War, 239).

3. Because he immersed himself in “the ordinary”

Nowadays travel can be – and is designed to be – simply more of the same Western style tourist hotels and consumer culture. Not so for Kapuściński. In the epigraph to his The Shadow of the Sun: My African Life (Penguin, 2001), he writes: “I lived in Africa for several years. I first went there in 1957. I returned whenever the opportunity arose. I travelled extensively, avoiding official routes, palaces, important personages, and high-level politics. Instead, I opted to hitch rides on passing trucks, wander with nomads through the desert, be the guest of peasants of the tropical savannah.”

The result is that through his writings we get a real sense of what the life of “the other” is like. His writings are full of real people with all the challenges and joys of their lives. What he uncovers is noteworthy. Kapuściński helped me, for example, get a sense of what real poverty is like. In his neighbourhood in Lagos was a solitary woman whose only possession was a pot. She survived by purchasing beans on credit, cooking, and selling them. One night, Kapuściński was woken by a piercing cry. The woman’s pot had been stolen. Reflecting on such theft he writes, “To be robbed is, first and foremost, to be humiliated, to be made a fool of. But with time I came to understand that seeing a robbery as a humiliation and an affront is an emotional luxury. Living amid the poverty of my neighbourhood, I realized that theft, even a petty theft, can be a death sentence” (The Shadow of the Sun, 111).

4. Because he shows us ourselves and the gift of the other

You could never accuse Kapuściński of being a romantic. His immersion shows us human life in all its brokenness and glory. There are harrowing accounts in his writings, but there are also moments of wonderful humanity. As he writes, “There is so much crap in this world, and then, suddenly, there is honesty and humanity” (The Soccer War, 82). Anthropologically, we might say that his accounts are thick rather than the sort of thin accounts of people and events that we have grown accustomed to. An important element in Kapuściński’s reflections in The Other is that it is through encounters with the other that we get to know ourselves: “Others … are the mirror in which I look at myself, and which tells me who I am” (The Other, Verso, 2008, 44–45).

A penetrating insight of Kapuściński’s is that encounter with the other need not involve collision but can open out into exchange. He tells the remarkable story of the juxtaposition of conflict and exchange during the civil war in Liberia in the early 1990s. The war front was a river joined by a bridge with a market on the government side. The shooting would continue unabated until midday and then, in the afternoon, peace would come, with the rebels crossing the bridge to shop at the market! They would hand their weapons to government representatives while they shopped and upon returning would receive back their weapons (The Other, 20–21).

One can, for example, juxtapose the loneliness that is pervasive in the West with African traditions of hospitality. In Dar es Salaam, Kapuściński writes of the hospitality he experienced. Neighbours started to invite him to their homes. He writes, “The saying ‘Guest in the house, God in the house’ has a nearly literal meaning here. The hosts prepare a long time for the occasion. They clean, they cook the best possible meal” (The Shadow of the Sun, 68). Here is a gift that we need in the West.

5. Because he understood journalism as mission

Ascherson observes that “not many of his readers have absorbed Kapuściński as a thinker, as an intellectual who enjoyed philosophical theorising and ethical reflection on the margins of Catholic theology” (The Other, 3). Kapuściński was deeply influenced by Father Józef Tischner, a Kraków theologian close to John Paul II. Tischner, like John Paul II, drew on the Jewish philosophy of Emmanuel Levinas, who positioned ethics and the face of the other at the heart of his philosophy. Kapuściński, too, is deeply influenced by Levinas, stressing the importance of the face of the other, of our responsibility for the other and that we encounter God in such encounters.

At the end of an interview in The Soccer War, Kapuściński reflects on why he does what he does. He answers: “Mine is not a vocation, it’s a mission. I wouldn’t subject myself to these dangers if I didn’t feel there was something overwhelmingly important – about history, about ourselves – that I felt compelled to get across. This is more than journalism” (The Soccer War, 244). Indeed it is. Here Kapuściński fingers that about journalism which is holy. It is a vocation, a sacred calling, vitally important for the well-being of our societies. It would be wonderful if KLC could contribute to the emergence of a new generation of investigative journalists like Kapuściński, and healthy, investigative news outlets. Our lives and those of our neighbours may depend on it.

Get the latest issue in print or subscribe for the next three.